From Mechanical Rules to Economic Reality, Governance, and Judgment

When to Recognize Revenue – Why “When” Still Matters More Than “How Much”

Revenue is the most politically sensitive number in the financial statements. It is the headline metric around which valuation, bonus schemes, debt covenants, analyst narratives, and market confidence revolve. Yet, despite decades of standard-setting, enforcement actions, and high-profile failures, the question “when should revenue be recognized?” remains one of the most judgment-laden decisions in financial reporting.

IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers was introduced with the explicit ambition to resolve long-standing inconsistencies and industry-specific loopholes. Its promise was deceptively simple: recognize revenue when performance occurs. In practice, however, IFRS 15 represents a profound conceptual shift—from a legalistic, risks-and-rewards paradigm to a control-based model grounded in economic substance.

This article explores when revenue should be recognized under IFRS 15—not as a checklist exercise, but as a question of economic reality, internal governance, documentation discipline, and professional judgment. We will move beyond the mechanics of the five-step model and examine how IFRS 15 reshapes behavior inside organizations, affects audit dynamics, and redefines accountability in the financial reporting ecosystem.

The Core Principle Revisited – Performance as the Anchor of Revenue

At the heart of IFRS 15 lies a single, unifying principle:

An entity shall recognize revenue to depict the transfer of promised goods or services to customers in an amount that reflects the consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for those goods or services.

This wording was deliberate and hard-fought. The standard setters sought to realign revenue recognition with actual performance, rather than contractual form, invoicing milestones, or cash flows. Revenue, under IFRS 15, is no longer merely the outcome of a signed contract—it is the accounting representation of value creation.

Crucially, the Boards explicitly decoupled performance from measurement uncertainty. Whether revenue should be recognized is conceptually separate from how precisely it can be measured. This distinction is foundational and frequently misunderstood in practice.

Under previous guidance, uncertainty often acted as a brake on recognition. If collectability was doubtful, or pricing was contingent, revenue recognition was deferred—even if the entity had clearly performed. IFRS 15 rejects this logic. Performance drives recognition; uncertainty is addressed through estimation, variable consideration constraints, and impairment models, not through recognition avoidance

From Risks and Rewards to Control – A Change of Mental Model

IAS 18 framed revenue recognition around the transfer of risks and rewards. While intuitive, this concept proved fragile in complex arrangements involving software, services, intellectual property, or long-term contracts. Risks and rewards could be split, shared, or retained in ways that obscured the economic reality of who truly controlled the asset.

IFRS 15 replaces this with a control-based model. Control exists when the customer has the ability to:

- Direct the use of the asset, and

- Obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from it.

This shift is not cosmetic. It forces preparers to analyze who can decide what happens next. Control is about decision-making power, not exposure alone. In many modern business models—platforms, cloud services, licensing arrangements—this distinction is decisive.

Importantly, control is assessed per performance obligation, not per contract. This granular focus significantly increases both analytical rigor and documentation requirements.

Read the effective date for IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers at ifrs.org.

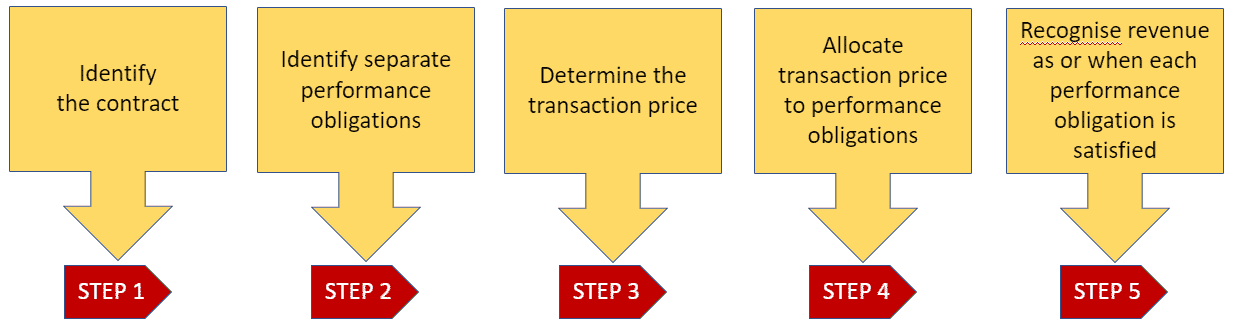

The Five-Step Model as a Governance Framework

The five-step model is often taught as a linear process. In practice, it functions more like an internal governance framework, requiring cross-functional coordination between sales, legal, operations, finance, and IT.

Step 1 – Identify the Contract: Legal Form Meets Economic Substance

A contract under IFRS 15 exists only if enforceable rights and obligations are present. However, enforceability is assessed not merely through legal theory, but through customary business practice.

Side letters, informal concessions, renewal patterns, and pricing behavior all influence the “accounting contract.” This is where governance enters the picture. Weak contract discipline or aggressive commercial practices can undermine revenue recognition positions long before auditors arrive.

Go to the detailed guidance in our blog on: Step 1. Identify the contract

Step 2 – Identify Performance Obligations: Where Judgment Lives

Separating performance obligations is arguably the most judgment-intensive step. Goods or services are distinct if they are both:

1. Capable of being distinct, and

2. Distinct within the context of the contract.

This second criterion is often underestimated. Even if a service could theoretically be sold separately, it may still be inseparable from the overall promise made to the customer.

The implications are profound. Performance obligation identification determines timing, pattern, and volatility of revenue. It is also a frequent focus of regulatory scrutiny, particularly in industries such as technology, construction, and telecommunications.

Go to the detailed guidance in our blog on: Step 2. Identify the performance obligations.

Step 3 – Determine the Transaction Price: “Entitled” Is Not “Invoiced”

IFRS 15 introduces a subtle but powerful concept: revenue is measured based on the consideration the entity expects to be entitled to, not necessarily the contractual or invoiced amount.

This expectation incorporates:

- Explicit price concessions

- Implicit concessions based on past practice

- Variable consideration subject to constraints

Notably, customer credit risk is generally excluded from the transaction price and addressed separately via impairment. This separation allows users to distinguish between operational performance and credit management effectiveness—a deliberate response to investor feedback.

An important exception exists when a significant financing component is present. In such cases, credit risk influences the discount rate, indirectly affecting revenue measurement.

Go to the detailed guidance in our blog on: Step 3. Determine the transaction price

Step 4 – Allocate the Transaction Price: Fairness over Formality

Allocation is performed based on relative standalone selling prices. When observable prices are unavailable, estimation techniques must be used. This step introduces model risk and demands methodological consistency.

From a governance perspective, allocation methodologies should be:

- Approved at an appropriate level

- Applied consistently across similar contracts

- Transparent and well-documented

Inadequate allocation frameworks are a recurring source of audit findings and regulator challenges.

Go to the detailed guidance in our blog on: Step 4. Allocate the transaction price

Step 5 – Recognize Revenue When (or As) Performance Obligations Are Satisfied

This final step brings us back to the central question: when does control transfer?

Performance obligations are satisfied either:

- At a point in time, or

- Over time, if specific criteria are met.

The over-time criteria—simultaneous receipt and consumption, customer-controlled asset creation, or lack of alternative use combined with enforceable right to payment—require careful analysis. They often hinge on contract enforceability, termination rights, and practical ability to redirect assets.

Read the original IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers standard at ifrs.org or go to the detailed guidance in our blog on: Step 5. Recognize the revenue

Timing Is Not Neutral – Behavioral and Economic Consequences

Revenue timing affects more than reported numbers. It shapes behavior.

- Sales teams may structure contracts to accelerate recognition.

- Management may prefer over-time recognition to smooth earnings.

- Bonus schemes may inadvertently incentivize aggressive interpretations.

IFRS 15 does not eliminate these pressures—it exposes them. The standard shifts responsibility from rule compliance to judgment governance. Boards, audit committees, and CFOs must ensure that revenue recognition policies reflect economic reality rather than performance targets.

Disclosure as the Second Pillar of Trust

IFRS 15 dramatically expands disclosure requirements. These disclosures are not ornamental; they are integral to the standard’s architecture.

Users are entitled to understand:

- How revenue is generated

- What judgments were applied

- Where uncertainty remains

Poor disclosures undermine even technically correct accounting. In enforcement actions, regulators increasingly focus on narrative transparency rather than numerical misstatement alone.

Read the Clarifications to IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers at ifrs.org.

No Simple Answers – Why IFRS 15 Is a Thinking Standard

As the original article correctly notes, IFRS 15 does not provide a shortcut answer to “how does this change my revenue?” The impact varies by business model, contract structure, and historical practice.

Some entities experience dramatic shifts; others see minimal numerical change but significant process transformation. Even when outcomes remain unchanged, controls, systems, and documentation almost always do.

IFRS 15 is therefore best understood not as a revenue standard, but as a discipline-imposing framework that forces organizations to articulate how they create value and when that value is delivered.

Revenue Recognition as an Indicator of Governance Maturity

Ultimately, how an organization applies IFRS 15 says more about its governance culture than about its accounting sophistication.

Strong applications are characterized by:

- Clear contract governance

- Cross-functional alignment

- Conservative treatment of ambiguity

- Transparent disclosure

- Robust documentation trails

Weak applications often reveal deeper issues: siloed decision-making, sales-driven accounting, and insufficient board oversight.

In this sense, revenue recognition becomes a diagnostic tool—a financial stethoscope placed on the heart of the organization.

Conclusion – Recognizing Revenue Is Recognizing Responsibility

IFRS 15 asks a deceptively simple question: when has the entity truly performed? Answering it requires more than technical competence. It demands integrity, judgment, and governance maturity.

Revenue is not merely recognized; it is earned, justified, and explained. IFRS 15 ensures that this process is no longer hidden behind industry conventions or contractual fine print.

For preparers, auditors, and boards alike, the standard is a reminder that financial reporting is not about speed or optimism, but about faithfully depicting economic reality—especially when that reality is complex.

FAQ’s – When to record turnover?

When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to record turnover IFRS 15 revenue recognition 5 steps

FAQ 1 – Why did IFRS 15 move away from the “risks and rewards” model?

The shift from a “risks and rewards” model (IAS 18) to a control-based model under IFRS 15 reflects the changing nature of modern business. Under IAS 18, revenue recognition often depended on whether significant risks and rewards of ownership had transferred. While workable for traditional product sales, this model struggled with complex arrangements such as software licenses, cloud services, long-term service contracts, and bundled offerings.

IFRS 15 focuses instead on who controls the asset or service. Control exists when the customer can direct the use of the asset and obtain substantially all of its remaining benefits. This perspective better captures economic reality in service-driven and digital business models, where legal ownership may never transfer, but value clearly does.

The control model also reduces structuring opportunities. Under IAS 18, entities could sometimes accelerate revenue recognition by shifting contractual risk clauses without changing actual performance. IFRS 15 limits this by anchoring recognition to performance obligations and satisfaction criteria.

From a governance perspective, this change increases the importance of judgment, documentation, and board oversight. Determining control requires a holistic analysis of contractual rights, practical ability, and economic substance—making revenue recognition a matter of professional accountability rather than mechanical compliance.

FAQ 2 – What does “expects to be entitled” really mean in IFRS 15?

The phrase “expects to be entitled” is one of the most conceptually important elements of IFRS 15. It deliberately departs from notions such as “amount invoiced,” “amount contracted,” or “amount expected to be collected.”

Under IFRS 15, revenue reflects the consideration the entity realistically expects to be entitled to, taking into account explicit and implicit price concessions, variable consideration, and customary business practices. If an entity routinely grants discounts, credits, or concessions—even if not contractually specified—those practices shape the accounting contract and therefore the transaction price.

Importantly, this concept separates pricing uncertainty from credit risk. Customer credit risk is generally excluded from the transaction price and addressed separately through impairment under IFRS 9. This allows users of financial statements to distinguish between operational performance and receivables management.

The concept requires discipline. Management must resist the temptation to recognize revenue at nominal contract values when historical behavior suggests otherwise. Auditors and audit committees increasingly focus on whether “entitlement” reflects reality or optimism. In this sense, “expects to be entitled” functions as both an accounting estimate and a governance integrity test.

FAQ 3 – When should revenue be recognized over time rather than at a point in time?

Revenue is recognized over time only if one of the specific criteria in IFRS 15 is met. These criteria are intentionally restrictive to prevent premature recognition.

Revenue is recognized over time when:

1. The customer simultaneously receives and consumes the benefits as the entity performs (typical for routine services).

2. The entity creates or enhances an asset that the customer controls as it is created.

3. The entity’s performance does not create an asset with alternative use, and the entity has an enforceable right to payment for performance completed to date.

If none of these criteria apply, revenue must be recognized at a point in time, even if the contract spans multiple periods.

In practice, the third criterion is often the most complex. It requires careful analysis of termination rights, contractual enforceability, and practical ability to redirect assets. This is a frequent area of regulatory challenge, particularly in construction, engineering, and customized manufacturing.

From a governance standpoint, over-time recognition demands robust project tracking, reliable progress measures, and strong internal controls. Without these, over-time recognition can quickly become a vehicle for earnings management rather than faithful representation.

FAQ 4 – How does IFRS 15 handle uncertainty without delaying revenue recognition?

One of the most important philosophical changes in IFRS 15 is that uncertainty no longer automatically delays revenue recognition. Under previous standards, uncertainty about pricing or collectability often prevented recognition altogether. IFRS 15 rejects this logic.

Instead, the standard separates:

– Recognition (driven by performance and control), and

– Measurement (addressing uncertainty through estimation and constraints).

Variable consideration is estimated using either the expected value or most likely amount method and then constrained to prevent significant revenue reversals. Credit risk is handled through impairment, not revenue deferral.

This approach improves transparency. Users can see revenue growth separately from bad debt experience, rather than having uncertainty buried in delayed recognition. However, it places greater responsibility on management judgment and estimation quality.

From a governance perspective, this increases the importance of documentation, consistency, and oversight. Boards and audit committees must ensure that estimation techniques are robust and unbiased. IFRS 15 does not reduce judgment—it reallocates it to where it belongs.

FAQ 5 – Why is identifying performance obligations so critical under IFRS 15?

Identifying performance obligations determines when and how revenue is recognized, making it one of the most consequential steps in IFRS 15. A performance obligation is a promise to transfer a distinct good or service to the customer.

The key challenge lies in assessing whether goods or services are distinct in the context of the contract. Even if items can be sold separately, they may still form a single combined output from the customer’s perspective.

Errors at this stage cascade through the entire revenue model:

– Incorrect timing (over time vs point in time),

– Misallocation of transaction price,

– Distorted margins and revenue profiles.

Because performance obligations often mirror how a business describes its value proposition, this step exposes inconsistencies between commercial storytelling and accounting reality. Regulators frequently scrutinize this alignment.

Strong organizations treat performance obligation identification as a cross-functional exercise involving sales, legal, operations, and finance. Weak organizations leave it to accounting after the deal is signed—often too late. In that sense, performance obligations are where revenue recognition meets organizational governance.

FAQ 6 – What does IFRS 15 reveal about an organization’s governance quality?

IFRS 15 functions as a governance stress test. Technically compliant revenue recognition can still reveal weaknesses in culture, incentives, and internal coordination.

Organizations with strong governance typically show:

– Clear contract approval processes,

– Consistent treatment of similar transactions,

– Conservative handling of uncertainty,

– Transparent disclosures explaining judgments.

Conversely, recurring revenue recognition issues often signal deeper problems: sales-driven accounting, inadequate documentation, or insufficient board oversight. Many enforcement cases involve not fraud, but overconfidence, optimism bias, or weak challenge culture.

The expanded disclosure requirements under IFRS 15 reinforce this. Entities must explain not just outcomes, but reasoning. This narrative accountability makes aggressive positions harder to defend after the fact.

Ultimately, IFRS 15 reminds stakeholders that revenue is not merely an accounting outcome—it is a representation of trust. How an organization recognizes revenue says a great deal about how it balances ambition with responsibility.

Read also: IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers – Best overview

When to Recognize Revenue

When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue When to Recognize Revenue