Back to the beginning of the standard

Standard 9 Reporting GHG Emissions

A credible GHG emissions report presents relevant information that is complete, consistent, accurate and transparent. While it takes time to develop a rigorous and complete corporate inventory of GHG emissions, knowledge will improve with experience in calculating and reporting data. It is therefore recommended that a public GHG report:

- Be based on the best data available at the time of publication, while being transparent about its limitations

- Communicate any material discrepancies identified in previous years

- Include the company’s gross emissions for its chosen inventory boundary separate from and independent of any GHG trades it might engage in.

Reported information shall be “relevant, complete, consistent, transparent and accurate.” The GHG Protocol Corporate Standard requires reporting a minimum of scope 1 and scope 2 emissions.

Required information

A public GHG emissions report that is in accordance with the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard shall include the following information:

DESCRIPTION OF THE COMPANY AND INVENTORY BOUNDARY

- An outline of the organizational boundaries chosen, including the chosen consolidation approach.

- An outline of the operational boundaries chosen, and if scope 3 is included, a list specifying which types of activities are covered.

- The reporting period covered.

INFORMATION ON EMISSIONS

- Total scope 1 and scope 2 emissions independent of any GHG trades such as sales, purchases, transfers, or banking of allowances.

- Emissions data separately for each scope.

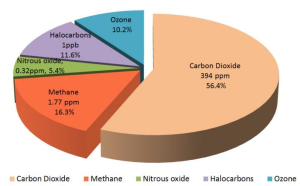

- Emissions data for all six GHGs separately (CO2, CH4, N2O, HFCs, PFCs, SF6) in metric tonnes and in tonnes of CO2 equivalent.

- Year chosen as base year, and an emissions profile over time that is consistent with and clarifies the chosen policy for making base year emissions recalculations.

- Appropriate context for any significant emissions changes that trigger base year emissions recalculation (acquisitions/divestitures, outsourcing/insourcing, changes in reporting boundaries or calculation methodologies, etc.).

- Emissions data for direct CO2 emissions from biologically sequestered carbon (e.g., CO2 from burning biomass/biofuels), reported separately from the scopes.

- Methodologies used to calculate or measure emissions, providing a reference or link to any calculation tools used.

- Any specific exclusions of sources, facilities, and / or operations.

Optional information

A public GHG emissions report should include, when applicable, the following additional information:

INFORMATION ON EMISSIONS AND PERFORMANCE

- Emissions data from relevant scope 3 emissions activities for which reliable data can be obtained.

- Emissions data further subdivided, where this aids transparency, by business units/facilities, country, source types (stationary combustion, process, fugitive, etc.), and activity types (production of electricity, transportation, generation of purchased electricity that is sold to end users, etc.).

- Emissions attributable to own generation of electricity, heat, or steam that is sold or transferred to another organization (see Standard 4 Setting operational Boundaries).

- Emissions attributable to the generation of electricity, heat or steam that is purchased for re-sale to non-end users (see Standard 4 Setting operational Boundaries).

- A description of performance measured against internal and external benchmarks.

- Emissions from GHGs not covered by the Kyoto Protocol (e.g., CFCs, NOx,), reported separately from scopes.

- Relevant ratio performance indicators (e.g. emissions per kilowatt-hour generated, tonne of material production, or sales).

- An outline of any GHG management/reduction programs or strategies.

- Information on any contractual provisions addressing GHG-related risks and obligations.

- An outline of any external assurance provided and a copy of any verification statement, if applicable, of the reported emissions data.

- Information on the causes of emissions changes that did not trigger a base year emissions recalculation (e.g., process changes, efficiency improvements, plant closures).

- GHG emissions data for all years between the base year and the reporting year (including details of and reasons for recalculations, if appropriate)

- Information on the quality of the inventory (e.g., information on the causes and magnitude of uncertainties in emission estimates) and an outline of policies in place to improve inventory quality. (see Guidance 7 Managing Inventory Quality).

- Information on any GHG sequestration.

- A list of facilities included in the inventory.

- A contact person.

INFORMATION ON OFFSETS

- Information on offsets that have been purchased or developed outside the inventory boundary, subdivided by GHG storage/removals and emissions reduction projects. Specify if the offsets are verified/certified (see Standard 8 Accounting for GHG Reductions) and/or approved by an external GHG program (e.g., the Clean Development Mechanism, Joint Implementation).

- Information on reductions at sources inside the inventory boundary that have been sold/transferred as offsets to a third party. Specify if the reduction has been verified/certified and/or approved by an external GHG program (see Standard 8 Accounting for GHG Reductions).

Guidance 9 Reporting GHG Emissions

By following the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard reporting requirements, users adopt a comprehensive standard with the necessary detail and transparency for credible public reporting. The appropriate level of reporting of optional information categories can be determined by the objectives and intended audience for the report. For national or voluntary GHG programs, or for internal management purposes, reporting requirements may vary (Appendix C summarizes the requirements of various GHG programs).

For public reporting, it is important to differentiate between a summary of a public report that is, for example, published on the Internet or in Sustainability/Corporate Social Responsibility reporting (e.g., Global Reporting Initiative) and a full public report that contains all the necessary data as specified by the reporting standard spelled out in this volume. Not every circulated report must contain all information as specified by this standard, but a  link or reference needs to be made to a publicly available full report where all information is available.

link or reference needs to be made to a publicly available full report where all information is available.

For some companies, providing emissions data for specific GHGs or facilities/business units, or reporting ratio indicators, may compromise business confidentiality. If this is the case, the data need not be publicly reported, but can be made available to those auditing the GHG emissions data, assuming confidentiality is secured.

Companies should strive to create a report that is as transparent, accurate, consistent and complete as possible. Structurally, this may be achieved by adopting the reporting categories of the standard (e.g., required description of the company and inventory boundary, required information on corporate emissions, optional information on emissions and performance, and optional information on offsets) as a basis of the report.

Qualitatively, including a discussion of the reporting company’s strategy and goals for GHG accounting, any particular challenges or trade-offs faced, the context of decisions on boundaries and other accounting parameters, and an analysis of emissions trends may help provide a complete picture of the company’s inventory efforts.

Double Counting

Companies should take care to identify and exclude from reporting any scope 2 or scope 3 emissions that are also reported as scope 1 emissions by other facilities, business units, or companies included in the emissions inventory consolidation (see Guidance 6 Identifying and Calculating GHG Emissions).

Use of ratio indicators

Two principal aspects of GHG performance are of interest to management and stakeholders. One concerns the overall GHG impact of a company—that is the absolute quantity of GHG emissions released to the atmosphere. The other concerns the company’s GHG emissions normalized by some business metric that results in a ratio indicator. The GHG Protocol Corporate Standard requires reporting of absolute emissions; reporting of ratio indicators is optional. Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions

Ratio indicators provide information on performance relative to a business type and can facilitate comparisons between similar products and processes over time.

Companies may choose to report GHG ratio indicators in order to: Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions

- Evaluate performance over time (e.g., relate figures from different years, identify trends in the data, and show performance in relation to targets and base years (see Guidance 11 Setting GHG Targets).

- Establish a relationship between data from different categories. For example, a company may want to establish a relationship between the value that an action provides (e.g., price of a tonne of product) and its impact on society or on the environment (e.g., emissions from product manufacturing).

- Improve comparability between different sizes of business and operations by normalizing figures (e.g., by assessing the impact of different sized businesses on the same scale).

It is important to recognize that the inherent diversity of businesses and the circumstances of individual companies can result in misleading indicators. Apparently minor differences in process, product, or location can be significant in terms of environmental effect. Therefore, it is necessary to know the business context in order to be able to design and interpret ratio indicators correctly.

Companies may develop ratios that make most sense for their business and are relevant to their decision making needs. They may select ratios for external reporting that improve the understanding and clarify the interpretation of their performance for their stakeholders. It is important to provide some perspective on issues such as scale and limitations of indicators in a way that users understand the nature of the information provided. Companies should consider what ratio indicators best capture the benefits and impacts of their business, i.e., its operations, its products, and its effects on the marketplace and on the entire economy. Some examples of different ratio indicators are provided here.

PRODUCTIVITY/EFFICIENCY RATIOS.

Productivity/efficiency ratios express the value or achievement of a business divided by its GHG impact. Increasing efficiency ratios reflect a positive performance improvement. Examples of productivity/efficiency ratios include resource productivity (e.g., sales per GHG) and process eco-efficiency (e.g., production volume per amount of GHG). Reporting GHG Emissions

|

MidAmerican: Setting ratio indicators for a utility company |

|

MidAmerican Energy Holdings Company, an energy company based in Iowa, wanted a method to track a power plant’s GHG intensity, while also being able to roll individual plant results into a corporate “generation portfolio” GHG intensity indicator. MidAmerican also wanted to be able to take into account the GHG benefits from planned renewable generation, as well as measure the impacts of other changes to its generation portfolio over time (e.g., unit retirements or new construction). The company adopted a GHG intensity indicator that specifically measures pounds of direct emissions over total megawatt hours generated (lbs/MWh). To measure its direct emissions, the company leverages data currently gathered to satisfy existing regulatory requirements and, where gaps might exist, uses fuel calculations. For coal-fired units, that means mainly using continuous emissions monitoring (CEM) data and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s emission factors for natural gas- and fuel oil-fired units. Using the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard, the company completes an annual emission inventory for each of its fossil-fired plants, gathering together a) fuel volume and heat input data, b) megawatt production data, c) CEMs data, and d) fuel calculations using appropriate emission factors. For example, in 2001, using CEM data and fuel calculations, the company’s Iowa utility business emitted roughly 23 million tonnes of CO2, while generating approximately 21 million megawatt hours. Its 2001 GHG intensity indicator calculates to approximately 2,177 lbs/MWh of CO2, reflecting the Iowa utility company’s reliance on traditional coal-fired generation. By 2008, the Iowa utility company will have constructed a new 790 MW coal-fueled plant, a 540 MW combined-cycle natural gas plant, and a 310 MW wind-turbine farm and added them to its generation portfolio. The utility company’s overall CO2 emissions will increase, but so will its megawatt production. The combined emissions from the new coal- and gas-fired plants will be added to the GHG intensity indicator’s numerator, while the megawatt production data from all three facilities will be added to the indicator’s denominator. More importantly, and the ratio indicator illustrates this, over time MidAmerican’s GHG intensity will decline as more efficient generation is brought online and older power plants are used less or retired altogether. |

INTENSITY RATIOS. Intensity ratios express GHG impact per unit of physical activity or unit of economic output. A physical intensity ratio is suitable when aggregating or comparing across businesses that have similar products. An economic intensity ratio is suitable when aggregating or comparing across businesses that produce different products. A declining intensity ratio reflects a positive performance improvement.

Many companies historically tracked environmental performance with intensity ratios. Intensity ratios are often called “normalized” environmental impact data. Examples of intensity ratios include product emission intensity (e.g., tonnes of CO2 emissions per electricity generated); service intensity (e.g., GHG emissions per function or per service); and sales intensity (e.g., emissions per sales).

PERCENTAGES. A percentage indicator is a ratio between two similar issues (with the same physical unit in the numerator and the denominator). Examples of percentages that can be meaningful in performance reports include current GHG emissions expressed as a percentage of base year GHG emissions.

For further guidance on ratio indicators refer to CCAR, 2003; GRI, 2002; Verfaillie and Bidwell, 2000. Reporting GHG Emissions

Guidance 10 Verification of GHG Emissions

Verification is an objective assessment of the accuracy and completeness of reported GHG information and the conformity of this information to pre-established GHG accounting and reporting principles. Although the practice of verifying corporate GHG inventories is still evolving the emergence of widely accepted standards, such as the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard and the forthcoming GHG Protocol Project Quantification Standard, should help GHG verification become more uniform, credible, and widely accepted. Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions

This chapter provides an overview of the key elements of a GHG verification process. It is relevant to companies who are developing GHG inventories and have planned for, or are considering, obtaining an independent verification of their results and systems. Furthermore, as the process of developing a verifiable inventory is largely the same as that for obtaining reliable and defensible data, this chapter is also relevant to all companies regardless of any intention to commission a GHG verification. Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions

Verification involves an assessment of the risks of material discrepancies in reported data. Discrepancies relate to differences between reported data and data generated from the proper application of the relevant standards and methodologies. In practice, verification involves the prioritization of effort by the verifier towards the data and associated systems that have the greatest impact on overall data quality.

Relevance of GHG principles

The primary aim of verification is to provide confidence to users that the reported information and associated statements represent a faithful, true, and fair account of a company’s GHG emissions. Ensuring transparency and verifiability of the inventory data is crucial for verification.

The more transparent, well controlled and well documented a company’s emissions data and systems are, the more efficient it will be to verify. As outlined in Standard 1. GHG Accounting and Reporting Principles, there are a number of GHG accounting and reporting principles that need to be adhered to when compiling a GHG inventory. Adherence to these principles and the presence of a transparent, well-documented system (sometimes referred to as an audit trail) is the basis of a successful verification. Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions

Goals

Before commissioning an independent verification, a company should clearly define its goals and decide whether they are best met by an external verification. Common reasons for undertaking a verification include:

- Increased credibility of publicly reported emissions information and progress towards GHG targets, leading to enhanced stakeholder trust Reporting GHG Emissions

- Increased senior management confidence in reported information on which to base investment and target-setting decisions Reporting GHG Emissions

- Improvement of internal accounting and reporting practices (e.g., calculation, recording and internal reporting systems, and the application of GHG accounting and reporting principles), and facilitating learning and knowledge transfer within the company Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions

- Preparation for mandatory verification requirements of GHG programs. Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions

Internal assurance

While verification is often undertaken by an independent, external third party, this may not always be the case. Many companies interested in improving their GHG inventories may subject their information to internal verification by personnel who are independent of the GHG accounting and reporting process. Both internal and external verification should follow similar procedures and processes. For external stakeholders, external third part verification is likely to significantly increase the credibility of the GHG inventory. However, independent internal verifications can also provide valuable assurance over the reliability of information.

Internal verification can be a worthwhile learning experience for a company prior to commissioning an external verification by a third party. It can also provide external verifiers with useful information to begin their work.

The concept of materiality

The concept of “materiality” is essential to understanding the process of verification. Standard 1. GHG Accounting and Reporting Priciples provides a useful interpretation of the relationship between the principle of completeness and the concept of materiality. Information is considered to be material if, by its inclusion or exclusion, it can be seen to influence any decisions or actions taken by users of it. A material discrepancy is an error (for example, from an oversight, omission or miscalculation) that results in a reported quantity or statement being significantly different to the true value or meaning.

In order to express an opinion on data or information, a verifier would need to form a view on the materiality of all identified errors or uncertainties. While the concept of materiality involves a value judgment, the point at which a discrepancy becomes material (materiality threshold) is usually pre-defined. As a rule of thumb, an error is considered to be materially misleading if its value exceeds 5% of the total inventory for the part of the organization being verified.

The verifier needs to assess an error or omission in the full context within which information is presented. For example, if a 2% error prevents a company from achieving its corporate target then this would most likely be considered material. Understanding how verifiers apply a materiality threshold will enable companies to more readily establish whether the omissions of an individual source or activity from their inventory is likely to raise questions of materiality.

Materiality thresholds may also be outlined in the requirements of a specific GHG program or determined by a national verification standard, depending on who is requiring the verification and for what reasons. A materiality threshold provides guidance to verifiers on what may be an immaterial discrepancy so that they can concentrate their work on areas that are more likely to lead to materially misleading errors. A materiality threshold is not the same as de minimis emissions, or a permissible quantity of emissions that a company can leave out of its inventory.

Assessing the risk of material discrepancy

Verifiers need to assess the risk of material discrepancy of each component of the GHG information collection and reporting process. This assessment is used to plan and direct the verification process. In assessing this risk, they will consider a number of factors, including:

- The structure of the organization and the approach used to assign responsibility for monitoring and reporting GHG emissions

- The approach and commitment of management to GHG monitoring and reporting

- Development and implementation of policies and processes for monitoring and reporting (including documented methods explaining how data is generated and evaluated)

- Processes used to check and review calculation methodologies

- Complexity and nature of operations

- Complexity of the computer information system used to process the information

- The state of calibration and maintenance of meters used, and the types of meters used

- Reliability and availability of input data

- Assumptions and estimations applied

- Aggregation of data from different sources

- Other assurance processes to which the systems and data are subjected (e.g., internal audit, external reviews and certifications).

Establishing the verification parameters

The scope of an independent verification and the level of assurance it provides will be influenced by the company’s goals and/or any specific jurisdictional requirements. It is possible to verify the entire GHG inventory or specific parts of it. Discrete parts may be specified in terms of geographic location, business units, facilities, and type of emissions. The verification process may also examine more general managerial issues, such as quality management procedures, managerial awareness, availability of resources, clearly defined responsibilities, segregation of duties, and internal review procedures.The company and verifier should reach an agreement upfront on the scope, level and objective of the verification.

This agreement (often referred to as the scope of work) will address issues such as which information is to be included in the verification (e.g., head office consolidation only or information from all sites), the level of scrutiny to which selected data will be subjected (e.g., desk top review or on-site review), and the intended use of the results of the verification). The materiality threshold is another item to be considered in the scope of work. It will be of key consideration for both the verifier and the company, and is linked to the objectives of the verification.

The scope of work is influenced by what the verifier actually finds once the verification commences and, as a result, the scope of work must remain sufficiently flexible to enable the verifier to adequately complete the verification.

A clearly defined scope of work is not only important to the company and verifier, but also for external stakeholders to be able to make informed and appropriate decisions. Verifiers will ensure that specific exclusions have not been made solely to improve the company’s performance. To enhance transparency and credibility companies should make the scope of work publicly available.

Site visits

Depending on the level of assurance required from verification, verifiers may need to visit a number of sites to enable them to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence over the completeness, accuracy and reliability of reported information. The sites visited should be representative of the organization as a whole. The selection of sites to be visited will be based on consideration of a number of factors, including:

- Nature of the operations and GHG sources at each site

- Complexity of the emissions data collection and calculation process

- Percentage contribution to total GHG emissions from each site

- The risk that the data from sites will be materially misstated

- Competencies and training of key personnel

- Results of previous reviews, verifications, and uncertainty analyses.

Timing of the verification

The engagement of a verifier can occur at various points during the GHG preparation and reporting process. Some companies may establish a semi-permanent internal verification team to ensure that GHG data standards are being met and improved on an on-going basis.

Verification that occurs during a reporting period allows for any reporting deficiencies or data issues to be addressed before the final report is prepared. This may be particularly useful for companies preparing high profile public reports.

However, some GHG programs may require, often on a random selection basis, an independent verification of the GHG inventory following the submission of a report (e.g., World Economic Forum Global GHG Registry, Greenhouse Challenge program in Australia, EU ETS). In both cases the verification cannot be closed out until the final data for the period has been submitted.

|

PricewaterhouseCoopers: GHG inventory verification — lessons from the field |

|

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), a global services company, has been conducting GHG emissions verifications for the past 10 years in various sectors, including energy, chemicals, metals, semiconductors, and pulp and paper. PwC’s verification process involves two key steps:

The GHG Protocol Corporate Standard has been crucial in helping PwC to design an effective GHG verification methodology. Since the publication of the first edition, PwC has witnessed rapid improvements in the quality and verifiability of GHG data reported. In particular the quantification on non-CO2 GHGs and combustion emissions has dramatically improved. Cement sector emissions verification has been made easier by the release of the WBCSD cement sector tool. GHG emissions from purchased electricity are also easy to verify since most companies have reliable data on Mwh consumed and emission factors are publicly available. However, experience has shown that for most companies, GHG data for 1990 is too unreliable to provide a verifiable base year for the purposes of tracking emissions over time or setting a GHG target. Challenges also remain in auditing GHG emissions embedded in waste fuels, co-generation, passenger travel, and shipping. Over the past 3 years PwC has noticed a gradual evolution of GHG verification practices from “customized” and “voluntary” to “standardized” and “mandatory.” The California Climate Action Registry, World Economic Forum Global GHG Registry and the forthcoming EU ETS (covering 12,000 industrial sites in Europe) require some form of emissions verification. In the EU ETS GHG verifiers will likely have to be accredited by a national body. GHG verifier accreditation processes have already been established in the UK for its domestic trading scheme, and in California for registering emissions in the CCAR. |

Selecting a verifier

Some factors to consider when selecting a verifier include their:

- previous experience and competence in undertaking GHG verifications

- understanding of GHG issues including calculation methodologies

- understanding of the company’s operations and industry

- objectivity, credibility, and independence.

It is important to recognize that the knowledge and qualifications of the individual(s) conducting the verification can be more important than those of the organization(s) they come from. Companies should select organizations based on the knowledge and qualifications of their actual verifiers and ensure that the lead verifier assigned to them is appropriately experienced. Effective verification of GHG inventories often requires a mix of specialized skills, not only at a technical level (e.g., engineering experience, industry specialists) but also at a business level (e.g., verification and industry specialists).

Preparing for a GHG verification

The internal processes described in Guidance 7 Managing Inventory Quality are likely to be similar to those followed by an independent verifier. Therefore, the materials that the verifiers need are similar. Information required by an external verifier is likely to include the following:

- Information about the company’s main activities and GHG emissions (types of GHG produced, description of activity that causes GHG emissions)

- Information about the company/groups/organization (list of subsidiaries and their geographic location, ownership structure, financial entities within the organization)

- Details of any changes to the company’s organizational boundaries or processes during the period, including justification for the effects of these changes on emissions data

- Details of joint venture agreements, outsourcing and contractor agreements, production sharing agreements, emissions rights and other legal or contractual documents that determine the organizational and operational boundaries

- Documented procedures for identifying sources of emissions within the organizational and operational boundaries

- Information on other assurance processes to which the systems and data are subjected (e.g. internal audit, external reviews and certifications)

- Data used for calculating GHG emissions. This might, for example, include:

- Energy consumption data (invoices, delivery notes, weigh-bridge tickets, meter readings: electricity, gas pipes, steam, and hot water, etc.)

- Production data (tonnes of material produced, kWh of electricity produced, etc.)

- Raw material consumption data for mass balance calculations (invoices, delivery notes, weighbridge tickets, etc.)

- Emission factors (laboratory analysis etc.).

- Description of how GHG emissions data have been calculated:

- Emission factors and other parameters used and their justification

- Assumptions on which estimations are based

- Information on the measurement accuracy of meters and weigh-bridges (e.g., calibration records), and other measurement techniques

- Equity share allocations and their alignment with financial reporting

- Documentation on what, if any, GHG sources or activities are excluded due to, for example, technical or cost reasons.

- Information gathering process:

- Description of the procedures and systems used to collect, document and process GHG emissions data at the facility and corporate level

- Description of quality control procedures applied (internal audits, comparison with last year’s data, recalculation by second person, etc.).

- Other information:

- Selected consolidation approach as defined in chapter 3

- List of (and access to) persons responsible for collecting GHG emissions data at each site and at the corporate level (name, title, e-mail, and telephone numbers)

- Information on uncertainties, qualitative and if available, quantitative.

Appropriate documentation needs to be available to support the GHG inventory being subjected to external verification. Statements made by management for which there is no available supporting documentation cannot be verified. Where a reporting company has not yet implemented systems for routinely accounting and recording GHG emissions data, an external verification will be difficult and may result in the verifier being unable to issue an opinion. Under these circumstances, the verifiers may make recommendations on how current data collection and collation process should be improved so that an opinion can be obtained in future years.

Companies are responsible for ensuring the existence, quality and retention of documentation so as to create an audit trail of how the inventory was compiled. If a company issues a specific base year against which it assesses its GHG performance, it should retain all relevant historical records to support the base year data. These issues should be born in mind when designing and implementing GHG data processes and procedures.

Using the verification findings

Before the verifiers will verify that an inventory has met the relevant quality standard, they may require the company to adjust any material errors that they identified during the course of the verification.

If the verifiers and the company cannot come to an agreement regarding adjustments, then the verifier may not be able to provide the company with an unqualified opinion. All material errors (individually or in aggregate) need to be amended prior to the final verification sign off.

As well as issuing an opinion on whether the reported information is free from material discrepancy, the verifiers may, depending on the agreed scope of work, also issue a verification report containing a number of recommendations for future improvements. The process of verification should be viewed as a valuable input to the process of continual improvement.

Whether verification is undertaken for the purposes of internal review, public reporting or to certify compliance with a particular GHG program, it will likely contain useful information and guidance on how to improve and enhance a company’s GHG accounting and reporting system.

Similar to the process of selecting a verifier, those selected to be responsible for assessing and implementing responses to the verification findings should also have the appropriate skills and understanding of GHG accounting and reporting issues.

Continue to Guidance 11 Setting GHG Targets

Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions Reporting GHG Emissions