Last Updated on 03/10/2025 by 75385885

Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance – When Two Giants Needed Each Other

At the end of the 1990s, the global car industry stood at a crossroads. Japan’s Nissan was teetering on the edge of collapse, crippled by debt and unable to launch competitive models. France’s Renault, smaller than its European rivals Volkswagen and PSA (now Stellantis), was looking for global scale and presence beyond Europe. The solution seemed obvious: an alliance that combined Renault’s engineering discipline and European footprint with Nissan’s technology and Asian reach. The Renault–Nissan Alliance started.

What followed, however, was not just an industrial partnership but a decades-long governance experiment. The Renault–Nissan–Mitsubishi Alliance became a textbook example of how strategic interdependence can clash with cultural divergence, national interests, and questions of control. It worked—until it didn’t.

This case is not only about cars. It is about how companies try to stitch together different DNA strands into a single organism. Sometimes the result is a healthy hybrid; sometimes it is a Frankenstein that cannot live.

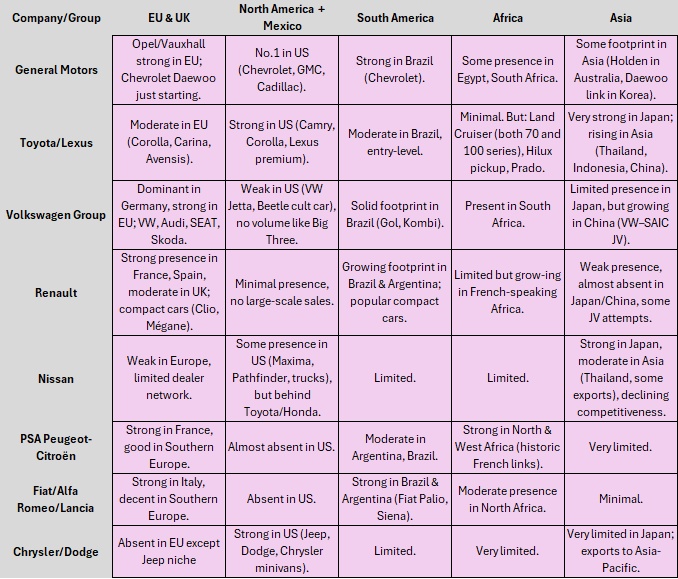

Car-manufacturers GEO Position Matrix (circa 1998–1999)

Starting Positions: Why Renault and Nissan Entered the Alliance

Renault’s Motivation

In the late 1990s Renault was profitable, but relatively small. Compared with Volkswagen, Toyota, and General Motors, its production volumes were modest. Renault needed:

- Scale economies: Renault wanted to save money by building more cars on the same basic platforms and sharing engines across different models. By producing higher volumes of the same components, costs per car would go down, making Renault more competitive.

- Geographical diversification: Renault’s business was concentrated in Europe, which meant that when the European market slowed down, Renault’s sales and profits were hit hard. By joining forces with Nissan, Renault gained access to new regions like Asia and North America, spreading its risks across more markets.

- Technological breadth: At the time, Renault was strong in small cars but lacked experience in growing segments like SUVs. Nissan already had know-how and successful SUV models. The alliance gave Renault the chance to expand into these areas more quickly than it could have on its own.

Renault’s government shareholder also wanted a flagship French industrial group with global ambition. For Renault, acquiring Nissan was not possible (too large, too indebted). But an alliance, without full merger, offered the benefits of reach without the risks of a hostile takeover.

Nissan’s Motivation

Nissan was in crisis. By 1999 it had nearly $20 billion in debt, an ageing product line, and a domestic market shrinking under demographic pressures. The banks were pressuring for restructuring. Without outside help, Nissan risked bankruptcy.

Why Renault? Because Renault offered cash, credibility, and no immediate intention to dominate. Renault acquired 36.8% of Nissan’s shares, giving it effective control but not outright ownership.

Nissan gained:

- Financial lifeline to reduce debt: By the late 1990s Nissan was burdened with almost $20 billion in debt. The alliance with Renault gave the company the cash it needed to pay back creditors and avoid collapse. Without that capital injection, Nissan might not have survived as an independent player.

- External discipline from Renault’s managers: Nissan had been struggling internally, with management hesitant to take tough decisions. The arrival of Renault executives brought a fresh, outsider’s perspective and the willingness to push through the painful restructuring steps that Nissan’s own leadership had delayed.

- Breathing space to cut costs and modernize: The deal bought Nissan valuable time. With Renault’s support, it could close unprofitable plants, renegotiate supplier contracts, and focus on updating its ageing product line. That breathing room allowed Nissan to rebuild its competitiveness in global markets.

It was an unequal alliance: Nissan was bigger, but weaker. Renault was smaller, but stronger. This asymmetry was baked into the governance structure.

Mitsubishi’s Later Entry

In 2016 Mitsubishi Motors, itself hit by scandal (fuel efficiency data falsification), joined the Alliance. Nissan bought 34% of Mitsubishi, pulling it into the orbit. On paper, it made sense: scale, Asian exposure, and shared platforms for small cars and SUVs. In reality, Mitsubishi became an appendix—useful, but never fully integrated.

The Renault–Nissan–Mitsubishi strategy was not fully implemented.

What Went Well – The Golden Years

The Alliance initially flourished. Under Carlos Ghosn, the “cost killer,” Nissan executed a brutal but effective turnaround:

- Debt reduction: Nissan repaid most of its massive debt within a few years.

- Product renewal: new models like the Nissan X-Trail, Qashqai, and 350Z revitalized the brand.

- Technology leadership: Nissan became a pioneer in electric vehicles with the Leaf.

Renault also benefited: shared platforms reduced costs, especially in compact and mid-sized vehicles. Combined, Renault and Nissan quickly became one of the world’s top car groups, rivalling Toyota, GM, and VW.

Governance-wise, the Alliance pioneered “cross-shareholding.” Renault owned 43% of Nissan; Nissan owned 15% of Renault (without voting rights). It was neither a merger nor a loose partnership. A central Alliance Board coordinated decisions.

The metaphor often used was a marriage without divorce: two partners bound together, but with separate homes.

Here is a writing by the hand of Carlos Ghosn in Harvard Business Review – Saving the Business Without Losing the Company.

What Went Wrong – Governance Cracks Appear

Structural Imbalance

From the beginning, the Alliance suffered from an imbalance: Renault controlled Nissan, but Nissan generated more sales and profits. Over time, Nissan executives resented being “junior” despite being the economic engine.

The Nissan–Renault governance was not balanced correctly.

Cultural Divide

Renault’s French engineering culture clashed with Nissan’s Japanese consensus style. Decision-making was slow, mistrust simmered, and informal power games replaced transparent governance.

Political Pressures

The French state, as Renault’s largest shareholder, saw the Alliance as a strategic asset. Japanese stakeholders viewed this with suspicion. When France pushed for closer integration, Nissan resisted.

The Ghosn Factor

Carlos Ghosn embodied the Alliance. He was celebrated as the savior, but also centralized power in himself. His leadership masked governance fragility. When Ghosn was arrested in 2018 on charges of financial misconduct, the Alliance lost its glue. Without him, old resentments resurfaced.

The affair illustrated a deeper lesson: when governance relies too heavily on one charismatic leader, the system itself may be hollow.

Mitsubishi’s Marginalization

Mitsubishi’s entry in 2016 looked like a way to boost volumes, but it never brought real coherence to the Alliance. The company had just been hit by a damaging fuel-efficiency data scandal, which undermined its credibility and weakened its bargaining position.

Financially, Mitsubishi was far smaller and structurally less profitable than Renault or Nissan, with thin margins and a limited global footprint outside Asia.

For Nissan, buying a 34% stake offered an opportunity to stabilize a partner in distress and to secure additional scale in small cars and SUVs. Yet in practice, Mitsubishi often acted more like a liability than a growth engine.

And here is an article on Insead – Designing Durable Alliances: Lessons From Renault-Nissan and the Alliance governance issues.

Governance Lessons from the Renault–Nissan–Mitsubishi Saga

- Balance matters: An alliance must respect economic realities. Renault’s legal control over a stronger Nissan was unsustainable.

- Cultural governance is as important as structures: Cross-shareholdings cannot paper over different corporate cultures.

- State shareholders complicate alliances: National interests may trump business logic.

- Beware of charismatic centralization: Strong leaders like Ghosn can deliver results but may obscure weak governance foundations.

- Flexibility vs. permanence: The Alliance model was designed to avoid a merger, but ended up paralyzing integration.

Read more on governance from a world-leader: ASML and the Power of Governance: From Underdog to Global Chip Machine Leader.

Comparison with Stellantis and Volkswagen Group – Robust Analysis

Stellantis: A Merger of Equals (Peugeot–Fiat–Chrysler)

History: Stellantis was born in 2021 from the merger of PSA (Peugeot-Citroën-Opel) and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA). PSA brought strength in Europe and efficiency in compact cars. Fiat Chrysler contributed Jeep and Ram, two of the most profitable brands in North America, plus Maserati and Alfa Romeo in the premium space.

Governance Model: Stellantis deliberately positioned itself as a merger of equals. The governance structure reflects balance:

- Equal representation on the board from PSA and FCA shareholders.

- A Dutch legal headquarters to avoid dominance by either France or Italy/US.

- Anchored shareholders include the Peugeot family, the Agnelli family (via Exor), and the French state, giving stability.

Contrast with Renault–Nissan:

- Renault–Nissan was an alliance without legal merger, creating permanent ambiguity over control.

- Stellantis is a single listed company, eliminating asymmetry.

- While Stellantis faces cultural challenges (French, Italian, American, German brands under one roof), the rules of engagement are clear from day one.

Lesson: Stellantis shows that clarity of ownership and governance is a stronger foundation than compromise structures. Where Renault–Nissan asked “who’s in charge?”, Stellantis answers “we both are, under one roof.”

Volkswagen Group: The Federal Model

History: VW evolved over decades into a multi-brand empire. Acquisitions of Audi (1960s), SEAT (1986), Skoda (1991), Bentley, Lamborghini, and Bugatti (1998), and Porsche (2012) transformed VW into the most diverse portfolio in the industry. By 2000, VW was already producing more than 5 million vehicles annually.

Governance Model: VW operates as a federal holding:

- Brands have strong autonomy in product development and identity (Audi is premium, Skoda is value, Porsche is performance).

- Group-wide platforms, purchasing, and technology deliver economies of scale.

- Anchored shareholders ensure stability: Porsche–Piëch family, State of Lower Saxony, and Qatar. This prevents hostile shifts of control.

Contrast with Renault–Nissan:

- VW’s anchored ownership contrasts with Renault–Nissan’s fragile cross-shareholding.

- VW brands accept group coordination because ownership is stable and legitimacy is clear.

- Renault–Nissan lacked legitimacy: Renault legally controlled Nissan, but Nissan delivered the majority of profits.

Lesson: VW demonstrates that a federation works when ownership and governance are not disputed. Renault–Nissan had the form of a federation, but without the glue of trust and stable ownership.

Similarities and Differences

- Scale: All three (VW, Stellantis, Renault–Nissan) sought global scale to compete with Toyota and GM.

- Cultural diversity: All three had to integrate different corporate cultures—VW with German, Czech, Spanish, Italian; Stellantis with French, Italian, American; Renault–Nissan with French, Japanese, later also Mitsubishi.

- Governance clarity: VW and Stellantis resolved governance at the structural level (holding company, merger of equals). Renault–Nissan tried to finesse it with cross-shareholdings, which proved unsustainable.

- Anchors vs. ambiguity: VW had anchored shareholders; Stellantis has balanced family and state anchors; Renault–Nissan relied on one man (Ghosn) and fragile structures.

Metaphor:

- VW is a federal state like Germany: strong Länder (brands) within a stable constitutional framework.

- Stellantis is a confederation treaty where two equal nations merged under a new constitution.

- Renault–Nissan was a domestic partnership without marriage contract, always vulnerable to disputes about property and status.

Conclusion – Can the Alliance Survive?

The Renault–Nissan–Mitsubishi Alliance is not dead, but it is wounded. In 2023–2024 steps were taken to rebalance: Renault reduced its stake in Nissan to around 15%, giving Nissan equal weight. This may calm tensions, but the industrial benefits have already eroded.

For students of governance, the case is a reminder that structures alone cannot create trust. Governance is not just about who owns what percentage. It is about aligning incentives, cultures, and political interests.

The Alliance started as a bold experiment, achieved miracles, but stumbled on its own contradictions. Its story stands as a parable for global corporations: partnerships are like marriages—without balance, trust, and renewal, even the strongest alliances decay.

Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance

Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance

FAQs Renault Nissan Mitsubishi

Why did Renault invest in Nissan in 1999?

Renault needed global scale and diversification. Nissan, though larger, was heavily indebted and needed a financial lifeline. Renault’s investment saved Nissan from collapse and gave Renault access to Asian markets.

What governance model did the Alliance use?

It relied on cross-shareholding: Renault owned 43% of Nissan; Nissan owned 15% of Renault without voting rights. Decisions were coordinated through an Alliance Board, not a holding company.

Why did the Alliance weaken after 2018?

The arrest of Carlos Ghosn exposed governance imbalances and mistrust. Without his leadership, cultural and structural tensions resurfaced, especially Nissan’s resentment of Renault’s control.

How does Stellantis differ from Renault–Nissan?

Stellantis was created by a full merger, ensuring equal governance between PSA and Fiat Chrysler. This avoided the imbalance of control vs. size that plagued Renault–Nissan.

How does Volkswagen manage its multi-brand empire?

VW uses a holding company model with strong anchored shareholders. Brands like Audi, Porsche, and Skoda retain autonomy but operate under a clear group governance framework.

What governance lessons apply to future alliances?

Successful alliances require balance, cultural alignment, clear governance, and less dependence on one leader. Without these, even strong industrial logic can unravel.

Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance

Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance Renault Nissan Mitsubishi Alliance governance