1. The Realisation Principle – Then and Now

The realisation principle has long stood at the core of accrual accounting: revenue is recognised only when it is earned and realised—that is, when goods or services have been delivered, or when risks and rewards have transferred to the customer. Under this traditional view, earning the revenue, not merely receiving cash, was the decisive event.

However, since the introduction of IFRS 15 – Revenue from Contracts with Customers, the focus shifted from risk and reward to transfer of control. Under IFRS 15.31–35, revenue is recognised when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation by transferring control of a promised good or service to the customer.

In other words: the old “realisation principle” has evolved into a performance-based recognition principle.

This modern framework provides a more faithful depiction of economic reality: entities recognise revenue when they deliver value to customers—not when cash happens to change hands.

2. From Concept to Standard – IFRS 15’s Five-Step Model

Every entity must follow the five-step workflow set out in IFRS 15.9–86:

| Step | Description | IFRS Reference | Key Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify the contract | Determine if an enforceable contract exists (approval, rights, payment terms, commercial substance). | IFRS 15.9–21 | Is there a valid contract with a customer? |

| 2. Identify performance obligations | Specify distinct goods or services to be transferred. | IFRS 15.22–30 | What exactly are we promising to deliver? |

| 3. Determine the transaction price | Estimate the amount of consideration expected, including variable components. | IFRS 15.47–72 | How much will we be entitled to receive? |

| 4. Allocate the transaction price | Assign the total price to each performance obligation based on relative stand-alone selling prices. | IFRS 15.73–86 | How is the price split across our promises? |

| 5. Recognise revenue | Record revenue when (or as) each obligation is satisfied, based on transfer of control. | IFRS 15.31–45 | Has control passed to the customer? |

This model operationalises the modern realisation concept and ensures comparability across industries.

IFRS 15’s Five-Step Model – The Story Behind the Numbers

When the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) introduced IFRS 15 – Revenue from Contracts with Customers, it wasn’t simply rewriting a rulebook. It was solving a problem that had haunted accountants for decades: When is revenue truly earned?

Across industries, companies were applying dozens of inconsistent standards—one for construction, another for software, and yet another for telecoms. The result?

Confusion, earnings management, and investor mistrust. IFRS 15 set out to change that by introducing one universal logic for all revenue: the five-step model.

Think of it as a story of trust between a company and its customer—a journey from handshake to headline revenue.

Step 1 – Identify the Contract (IFRS 15.9–21)

Why: Because not every handshake is a contract.

Imagine a company selling solar panels to homeowners. A friendly conversation, a quote, a nod of agreement—does that already create revenue?

Under IFRS 15, no. Before revenue can be recognised, there must be a contract that creates enforceable rights and obligations.

To qualify, five criteria must be met:

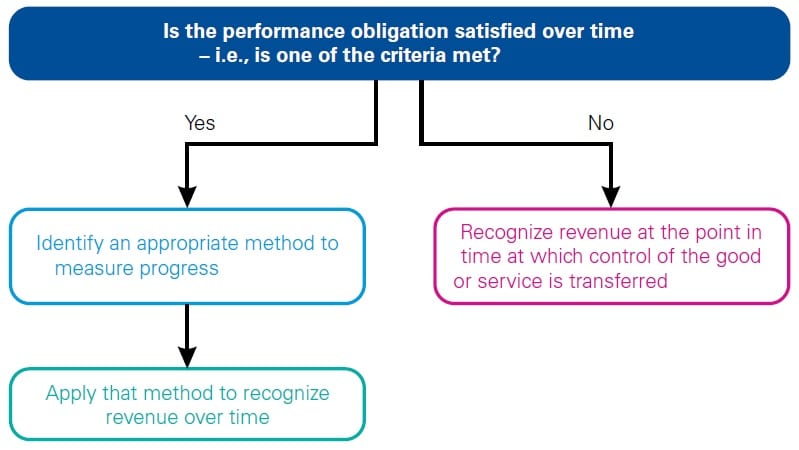

3. Key Recognition Triggers

Revenue is not recognised on cash receipt, but rather when control passes. IFRS 15 distinguishes:

- Point-in-time recognition (IFRS 15.38–45):

Control transfers at a specific moment—often delivery, acceptance, or installation. - Over-time recognition (IFRS 15.35):

Control transfers continuously, e.g., in construction, SaaS, or long-term maintenance contracts.

The over-time recognition class is the defined one. If not meeting the criteria for IFRS 15.25 the type of recognition id point-in-time.

Entities must assess indicators of control transfer: legal title, physical possession, significant risks and rewards, and acceptance by the customer.

Here is the original PDF of IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers at IFRS.org

4. Six Case Examples – How the Realisation Principle Works in Practice

Below are six practical examples illustrating how the traditional realisation idea now operates under IFRS 15. Each follows the five-step workflow.

Case 1 – Advance Sale of Goods (Point-in-Time)

Scenario:

On 23 February 20X1, Entity A receives EUR 20 000 as an advance payment for goods to be delivered on 5 April 20X1.

Step-by-step analysis:

- Identify contract – Valid agreement exists (IFRS 15.9).

- Identify performance obligation – One obligation: delivery of goods (IFRS 15.22).

- Determine transaction price – EUR 20,000 (IFRS 15.47).

- Allocate price – Not applicable (single obligation).

- Recognise revenue – At the point in time control transfers (delivery) → See IFRS 15.38–40.

Journal entries:

At contract inception:

Dr Cash 20,000 | Cr Contract liability (deferred revenue) 20,000 – Entity A received advance and records a liability to deliver the goods, as soon as the advance is recorded in the bank account.

At delivery:

Dr Contract liability 20,000 | Cr Revenue 20,000 – The goods have been delivered, so the Performance Obligation has been fulfilled and Revenue is recognised.

Result: Revenue recognised on 5 April 20X1, not on cash receipt.

Case 2 – Software Subscription with Updates (Over-Time)

Scenario:

Customer pays EUR 6,000 for a one-year software licence with continuous updates and technical support.

Analysis (IFRS 15.35(a)):

- Contract identified.

- Two performance obligations: software access + updates/support.

- Transaction price = EUR 6,000.

- Allocate (e.g., 60 % software = 6,000 x 60% = 3,600 / 40 % support = 6,000 x 40% = 2,400).

- Recognise revenue over time because the customer simultaneously receives and consumes benefits (IFRS 15.35(a)). Monthly revenue calculation: 3,600/12 + 2,400/12 = 300 + 200 =

500/month

Recognition pattern: Straight-line over 12 months.

Journal entries:

At contract inception:

Dr Cash 6,000 | Cr Contract liability (deferred revenue) 6,000

Revenue recognition over time:

Dr Contract liability (deferred revenue) 500 | Cr Revenue 500 (per month)

Case 3 – Construction Contract (Percentage of Completion)

Scenario:

A construction company builds a bridge for EUR 10 million over two years.

Application:

- Contract – approved; enforceable rights.

- Performance obligation – build one bridge.

- Transaction price – EUR 10 million

- Allocate – single obligation.

- Recognise revenue over time under IFRS 15.35(b) because the asset is constructed on the customer’s site and has no alternative use.

Progress measure: Cost-to-cost method (IFRS 15.39–45).

If 40 % complete at year-end:

Revenue = EUR 4 million (= 10 million * 40%)

At year-end:

Journal entry:

Dr Contract asset 4,000,000 / Cr Revenue recognised 4.000,000 (per IFRS 15.117–121),

Payments as per contract: Dr Cash 4,500,000 / Cr Contract liabilities 4,500,000,

In the year/end close the balances Dr Contract assets 4,000,000 and Cr Contract liabilities would be netted because they come from one and the same contract, Cr contract liabilities 500,000.

Note – Since the case states the project is 40% complete, you do not need to calculate the estimated cost to complete or the actual costs incurred—the percentage is given. However, in practice, the company would use the Cost-to-Cost ratio (or a similar method like surveys of work performed or labor hours) to arrive at the 40%

Case 4 – Combined Sale of Truck and Maintenance Contract (Multiple Obligations)

Scenario:

XXX Truck Factory Co. Ltd sells a truck with a one-year maintenance package.

Workflow:

- Contract valid.

- Two performance obligations: truck delivery + maintenance service.

- Transaction price = EUR 100,000.

- Allocate: Truck EUR 90,000, with an advance of 30% when the contract is signed; Maintenance EUR 10,000 for 12 months (IFRS 15.73–86).

- Recognise:

- Truck → point in time (delivery).

- Maintenance → over time (monthly).

IFRS refs: 15.22, 15.73, 15.35(a).

Result: Split recognition pattern increases transparency and aligns with substance of the transaction.

At contract inception:

Advance receipt 90,000 x 30% = 27,000, Journal entry: Dr Cash 27,000 / Cr Contract liability (deferred revenue) 27,000

At delivery:

Journal entry: Dr Contract liability (deferred revenue) 27,000 / Dr Bank 100,000 -/- 27,000 = 73,000 / Cr Revenue 90,000 / Cr Deferred revenue 10,000

Maintenance 12 months revenue over time:

Journal entry: Dr Deferred revenue 833 (= 10,000 /12) / Cr Revenue 833

Case 5 – Licensing with Sales-Based Royalties (Variable Consideration)

Scenario:

Music Co. grants a licence to stream songs and receives a 5 % royalty on sales.

IFRS 15.B63 requires that sales- or usage-based royalties tied to a licence are recognised only when the subsequent sale or usage occurs—not when the licence is granted.

Workflow:

- Contract identified.

- Performance obligation: right to access IP.

- Transaction price variable.

- Allocate entirely to the licence.

- Recognise revenue as sales occur.

Journal:

Dr Receivable X | Cr Revenue X (5 % of actual sales)

Case 6 – Consignment Arrangement (Control Retained)

Scenario:

Entity B delivers goods to a dealer on consignment. Dealer sells to end customers.

Under IFRS 15.B77–B78:

Control does not pass to the dealer upon shipment; risks remain with the consignor.

Revenue recognition:

Only when the dealer sells the goods to the end customer.

Journal impact:

Until sale: inventory remains on consignor’s books.

At sale:

Dr Receivable / Cash | Cr Revenue | Cr COGS

This prevents premature recognition—one of the classic violations of the realisation principle.

5. Matrix Summary – Realisation under IFRS 15

| # | Scenario | Type | IFRS 15 Reference | Recognition Timing | Control Indicator | Main Journal Entry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Advance goods sale | Point-in-time | 15.38–40 | On delivery | Transfer of title | Contract liability → Revenue |

| 2 | Software subscription | Over-time | 15.35(a) | Evenly over period | Simultaneous receipt of benefit | Liability → Revenue (monthly) |

| 3 | Construction project | Over-time | 15.35(b)–(c) | Based on progress | No alternative use | Asset → Revenue (proportionally) |

| 4 | Truck + maintenance | Mixed | 15.73–86 / 15.35(a) | Split (delivery + service) | Separate obligations | Revenue split |

| 5 | Licence + royalties | Variable | 15.B63 | As sales occur | Usage-based | Receivable → Revenue |

| 6 | Consignment | Point-in-time (delayed) | 15.B77–B78 | On customer sale | Retained control | Revenue when sold |

See also IFRS 15 Review of Accounting Standard on revenue.

6. Common Pitfalls and Misinterpretations under IFRS 15 – Where Good Intentions Go Wrong

IFRS 15 was designed to bring order to chaos.

Yet, in boardrooms and audits across the world, the same errors appear again and again.

Not because accountants are careless, but because commercial pressure, judgement calls, and complexity make the five-step model easy to misread.

Let’s explore the most frequent traps — not as dry bullet points, but as stories of how logic, optimism, or convenience can derail sound reporting.

6.1 Mistaking Cash for Performance

Many finance teams still fall into the oldest trap in accounting: assuming that receiving cash equals earning revenue.

A customer pays a €100 000 advance for bespoke machinery; the bank account looks healthy, management celebrates — and someone books revenue.

But under IFRS 15.9–21, the cash is irrelevant until the entity has a contract and has transferred control of the promised goods or services.

The result of jumping the gun is a contract liability that never appears — and a profit that doesn’t exist.

When auditors correct it, confidence suffers.

IFRS 15 deliberately separates liquidity from performance: money can move before or after value is delivered.

That distinction is the moral heart of accrual accounting.

6.2 Bundling Everything Together

Another common failure is the “one-bucket syndrome.”

A company sells a product, a warranty, and ongoing cloud access.

Instead of unbundling them, it books all revenue on the shipment date — arguing that the “sale” is complete.

Under IFRS 15.22–30, each distinct good or service must be identified as a separate performance obligation.

If the cloud access provides continuous benefit, that part of the consideration belongs to the future, not to day one.

The motivation behind bundling is often innocent — simplification — but its impact is dangerous.

It front-loads profits, hides future commitments, and distorts performance indicators.

True governance requires resisting that temptation and recognising that “one deal” can still contain many promises.

6.3 Over-optimism in Variable Consideration

Executives love performance bonuses.

So do their forecasts.

But IFRS 15 demands restraint: variable consideration (discounts, bonuses, penalties, royalties) may only be recognised when it is highly probable that a significant reversal will not occur (IFRS 15.56–58).

Here is where many organisations stumble.

They include potential bonuses as soon as a project “looks on track.”

Later delays or disputes force reversals — eroding trust and inviting scrutiny.

The standard’s built-in constraint is a test of character: record what you know, not what you hope.

As one auditor once quipped, “IFRS 15 isn’t against optimism; it just insists on evidence.”

6.4 Ignoring Progress Measurement

In long-term contracts — think construction, software implementation, shipbuilding — IFRS 15 allows over-time recognition only when performance can be measured reliably (IFRS 15.35–45).

Yet many companies treat the percentage of completion as an accounting decoration rather than a discipline.

They use cost data that lags by months, ignore rework, or rely on unverified engineer estimates.

When reality catches up, margins collapse.

Progress measurement is not about spreadsheets; it’s about control of information flow.

If operational data are unreliable, financial data will be fiction.

Strong internal controls, independent validation, and regular recalibration are the only defence.

6.5 The “Delivery Equals Control” Fallacy

For decades, accountants were trained to think in terms of risk and reward transfer.

Trucks leaving the warehouse meant “sale complete.”

IFRS 15 replaced that logic with transfer of control, yet many still use the old shortcut.

Consider consignment arrangements or goods subject to installation and testing.

Until the customer can direct the use of the asset and obtain substantially all benefits, control has not transferred (IFRS 15.33–38, B77–B78).

Revenue booked on shipment must therefore be reversed if significant risks remain.

The psychological trap is subtle: delivery feels tangible, while “control” sounds abstract.

But the essence of IFRS 15 is to look beyond the warehouse door — to who truly owns the outcome.

6.6 Forgetting to Reassess Contracts

Projects evolve.

Prices change, scope expands, and deadlines move.

Yet many entities treat the contract analysis as a one-off exercise.

IFRS 15.20 and 15.88–90 require continuous reassessment:

- Have new performance obligations been added?

- Should the old contract be modified or replaced?

- Does the change represent a separate contract?

Ignoring these triggers leads to inconsistent revenue patterns and hidden obligations.

Contract management systems must talk to finance — otherwise, the five-step model freezes in time while reality moves on.

6.7 The Missing Documentation

Even when recognition is technically correct, lack of documentation undermines compliance.

Under IFRS 15.123–126, entities must disclose significant judgements about timing, methods of measuring progress, and allocation.

Many teams underestimate this requirement.

They assume “the numbers speak for themselves.”

They don’t.

Without a clear narrative — why you recognised revenue over time, how you estimated variable consideration — the audit trail collapses.

Good documentation is not bureaucracy; it’s protection.

It explains the reasoning behind every recognition decision and allows future reviewers to trace logic, not just ledger entries.

6.8 Misalignment between Finance and Operations

Perhaps the most human of all pitfalls: the communication gap.

Sales signs the contract, operations deliver, finance records — yet none fully understand the other’s interpretation.

The result?

Finance books revenue when operations have not yet completed deliverables, or operations recognise milestones that finance cannot substantiate.

IFRS 15 depends on collaboration: the “five steps” are not five departments but one process.

Best practice is to build an internal revenue recognition committee where commercial, legal, and finance staff review material contracts before signing.

That’s governance in action.

6.9 The Governance Blind Spot

IFRS 15 is often treated as an accounting issue, but it is equally a governance issue.

Audit committees should understand the judgements driving revenue timing, yet many boards delegate the topic entirely to controllers.

Revenue is not just a number — it’s the most watched signal of performance.

Weak oversight here can mislead investors faster than any balance sheet misstatement.

Good boards ask:

- What assumptions drive our revenue?

- How sensitive are results to changes in timing or estimates?

- Do disclosures tell the full story?

A board that cannot answer these questions is governing blindfolded.

6.10 The Illusion of Simplicity

Perhaps the deepest misinterpretation is believing that IFRS 15 is a checklist.

Five steps, a flowchart, a few tables — and done.

But every step demands professional judgement: is the service distinct, is progress measurable, is consideration variable, is control transferred?

When management treats IFRS 15 as mechanical, the spirit of the standard is lost.

Revenue recognition is not about ticking boxes; it’s about capturing reality faithfully.

As soon as accountants forget that, they stop being narrators of business truth and become mere bookkeepers of numbers.

Why These Pitfalls Persist

Three forces explain why the same mistakes keep resurfacing:

- Commercial pressure: management bonuses linked to revenue growth.

- Legacy habits: staff trained under IAS 18 or US GAAP equivalents.

- Information silos: accounting data disconnected from operational progress systems.

IFRS 15 demands a cultural shift — from “recording sales” to measuring performance.

Without that shift, even technically correct entries can misrepresent substance.

Learning from the Mistakes

Every pitfall tells a governance story:

- The over-eager CFO who books bonuses too early.

- The project manager who hides delays to keep margin forecasts alive.

- The accountant who accepts delivery notes as proof of control.

They are not villains — they are reminders that accounting is behavioural science with numbers attached.

The five-step model works only when each step is anchored in ethical discipline.

Strong organisations institutionalise that discipline: they integrate contract management, internal audit, and disclosure review into one continuous loop.

That is how you turn IFRS 15 from a compliance burden into a competitive advantage.

Realisation principle

Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle

In the End – Revenue as a Test of Character

The realisation principle used to be simple: recognise revenue when earned.

IFRS 15 made it richer, fairer, and far more demanding.

It asks not just “when did we sell?” but “when did we truly deliver value?”

The common pitfalls show that the biggest risk is not misunderstanding the rules — it’s forgetting their purpose.

Revenue recognition is the moral mirror of a company’s business model: it reflects how honestly performance is measured and communicated.

When CFOs, auditors, and boards respect that mirror, the numbers tell the truth — and investors can believe the story behind them.

See also Post-implementation Review of IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers.

7. The Principle in Governance and Reporting

The realisation principle—modernised through IFRS 15—protects the integrity of reported earnings. It enforces discipline: performance before profit.

Good governance requires audit committees and CFOs to ensure that:

- Contract identification follows formal criteria.

- Significant judgements are documented (IFRS 15.123–126).

- Disclosures on performance obligations are transparent (IFRS 15.114–116).

When consistently applied, this principle transforms financial reporting from an income statement exercise into a trust mechanism for investors.

Also read: WalllStreetmojo

FAQs – The Realisation Principle

Q1. What is the main difference between the traditional realisation principle and IFRS 15?

The old principle focused on transfer of risks and rewards. IFRS 15 replaces this with transfer of control, supported by a structured five-step model that determines when and how much revenue to recognise.

Q2. Why is revenue not recognised when cash is received?

Because cash inflows may occur before performance (advance payments) or after (credit sales). Under accrual accounting, revenue is recognised only when the entity fulfils its obligations, not when liquidity changes.

Q3. When is revenue recognised “over time”?

When the customer simultaneously receives and consumes benefits, controls an asset as it is created, or when the asset has no alternative use and the entity has an enforceable right to payment (IFRS 15.35).

Q4. What disclosures are required?

Entities must disclose significant judgements, timing of satisfaction of performance obligations, and balances of contract assets/liabilities (IFRS 15.117–127).

Q5. How does the realisation principle enhance governance?

By ensuring that profits reflect actual performance, it deters earnings manipulation and provides transparency on timing and risks in revenue streams.

Realisation principle

Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle Realisation principle