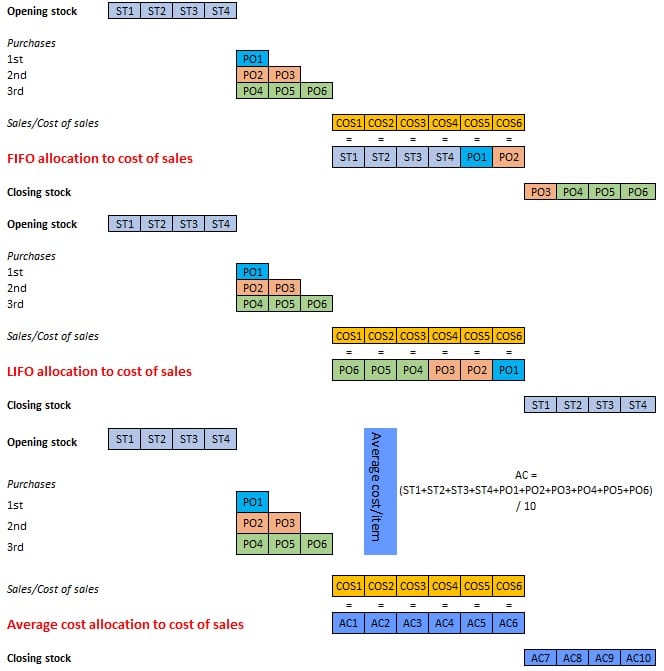

Inventory costing – is about costs allocated to value inventory in stock at the end of a reporting period and calculate the costs of sales/gross profit earned in a period. Most operations comprise retail or wholesale operations, using relatively simple inventory costing systems such as FIFO, LIFO or Average Costs, other operations such as manufacturing or servicing/construction use standard or actual costing systems.

Also keep in mind that the general rule in IFRS is that inventory is measured as the lesser of cost or net realizable value.

For context – Net realizable value

There are a number of different inventory costing methods available for Inventory / Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) valuations/allocations. Perpetual systems continuously update the inventory, avoiding issues inherent with periodic based systems. For cost flow, there are three (3) regularly used cost methodologies in the world: FIFO, LIFO, and Weighted-Average Cost (also commonly referred to as Average Cost).

- FIFO or First-In, First-Out, always assigns the cost of the earliest unit available at the time of sale to COGS, regardless of which unit from the inventory pool is used.

- LIFO or Last-In, First-Out, always assigns the cost of the newest unit available at the time of sale to COGS, regardless of which unit from the inventory pool is used.

- Average Cost calculates the cost that is assigned to COGS and inventory each period closing with new units purchased and added to the inventory.

However, there are also more complex inventory costing systems that facilitate the (financial and operational) management of manufacturing and servicing activities, reference is made to standard costs and actual costs.

To visualize the difference of these three systems (FIFO, LIFO and Average Costs) here is a simple case in quantities of one product in inventory only:

The Case:

|

Opening stock 1 March 20×2 |

4 items in stock, ST1, ST2, ST3, ST4 |

|

Purchases March 20×2 |

1st purchase order, 1 item PO1 |

| Inventory costing Inventory costing Inventory costing Inventory costing Inventory costing Inventory costing |

2nd purchase order, 2 items PO2, PO3 |

| Inventory costing Inventory costing Inventory costing Inventory costing Inventory costing Inventory costing |

3rd purchase order, 3 items P04, PO5, PO6 |

|

Sales March 20×2 |

6 items were sold in the period (COS1, COS2, COS3, COS4, COS5, COS 6) |

|

Closing stock 31 March 20×2 |

4 items in stock at the end of the reporting period |

This results in the following Inventory / Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) valuations/allocations:

In practice – What is the effect of each system?

Three retailing US giants, Amazon.com, Inc., (NASDAQ: AMZN), and Target Corporation (NYSE: TGT) and Best Buy Co., Inc. (NYSE: BBY) each use a different inventory costing method. Amazon uses FIFO, Target uses LIFO and Best Buy uses weighted-average cost.

Here is one simple case to show the differences in applying these three systems:

Assume that all three retailers sell a popular trouser that sells for $32/trouser. To compare the impact of inventory costing method, also assume that all three retailers have the following inventory and sales data for the same period. To keep the calculations simple, a “unit” represents one million trousers.

- Beginning inventory: 3 units @ $10.00

- Purchases: 2 units @ $15.00

- Ending inventory: 1 unit

Sales are calculated as follows:

begin 3 plus purchases 3 is 5 available for sale,

less ending (not sold) 1 ===> sold 4 units.

Amazon – FIFO

Sold 4 units, 3 from beginning inventory and 1 from purchases

Cost of sales: 3 units @ $10.00 from beginning inventory and 1 unit @ $15.00 from purchases = $45.00

Ending inventory: 1 unit @ $15.00 from purchases = $15.00

Target – LIFO

Sold 4 units, 2 from purchases and 2 from beginning inventory

Cost of sales: 2 units @ $15.00 from purchases and 2 unit @ $10.00 from beginning inventory = $50.00

Ending inventory: 1 unit @ $10.00 from beginning inventory = 10.00

Best Buy – Weighted-average cost

Sold 4 units, average cost calculation:

Beginning inventory: 3 units @ $10.00 plus purchases: 2 units @ $15.00 = total costs $60.00 for 5 units,

Average costs $60.00 / 5 = $12.00/unit

Cost of sales: 4 units @ $12.00 = $48.00

Ending inventory: 1 unit @ $12.00 = $12.00

OR in comparison:

| FIFO | LIFO | AC | |

| Revenue from sales 4 units @ $32.00 | 128.00 | 128.00 | 128.00 |

| Cost of sales 4 units | 45.00 | 50.00 | 48.00 |

| Gross profit | 83.00 | 78.00 | 80.00 |

| In % of revenue | 65% | 61% | 63% |

| Ending inventory | 15.00 | 10.00 | 12.00 |

FIFO results in the remaining items in inventory being accounted for at the most recent purchase/market price (purchase input side), so inventory costing on the balance sheet is relatively high, with potentially higher risks for obsolescence. In addition FIFO also results in matching older purchase costs with current sales prices, so one may argue this does not reflect a proper matching of revenues and costs. The FIFO valuation method is the most commonly used inventory valuation method as most of the companies sell their products in the same order in which they purchase it.

LIFO is just the other way around, remaining items in inventory are valued prudently at low(er) old purchase prices, but matches current purchase costs with current sales prices. However LIFO is not allowed under IFRS! It assumes that the most recently purchased or manufactured items are sold first.

Average costs results in something in between, with the advantage that the perpetual system does not have to take into account layers of beginning inventory, purchases and sales. This method is mainly used by businesses that don’t have variation in their inventory. Average costs is allowed under IFRS.

Note: increases or decreases in sales and purchase prices may lead to very different outcomes, the example is hypothetical.

Standard costing

Standard costing is generally applied to manufacturing activities, but can be applied in other environments (i.e. service environment):

- Common / repetitive operations

- Input to produce output can be specified

- Can be applied where different products are produced, as long as there are common operations / processes

Standard costing is predetermined per product type/production department/production phase, and represent target costs under normal efficient operating conditions.

The difference between a budget and standard costing is that a budget is for a total activity, whereas standard costing represents the budget per unit of the units of budgeted production.

A standard cost is effectively a budget or target cost that is applied to both purchased and manufactured items. With standard costing, every item that is bought or made is given a standard cost. If a manufacturer holds routing information (i.e. details of resources such as labor and machines, along with process times) on the system, it would be normal to just enter standard costs for materials and resources and then have the system calculate the processing costs via a process usually known as a “cost roll-up”.

Traditionally, standard costs are re-calculated yearly and, if companies find they are re-calculating them much more frequently, that is usually a sign that standard costing is not appropriate for them.

Having set a standard cost for each item, all transactions for that item are then costed at that standard until it is changed. In real life, of course, the actual cost will frequently differ, as purchase costs can vary, as will manufacturing costs because process times can vary from batch to batch. This is actually the strength of standard costing because every time there is a variance between standard (budget) and actual costs, that variance is written to a variance account in the financial system.

By monitoring the variance accounts regularly, companies can check that costs are broadly in line with expectations and that profitably, in consequence, is likely to be on target also. Of course, companies can get positive variances when costs are less than expected. This can be a sign that it may be possible to increase market share by reducing selling prices, but it would be wise to check carefully first!

If costs are out of line with expectations, the system should be able to identify where the problems are; be they problems with the cost of particular materials or with a failure or inability to manufacture products within expected times. Only by knowing where the problems are can they be remedied and, for that reason, it is imperative that the variance accounts are structured carefully and checked regularly. It is not good enough to get to the end of the financial year before noticing that costs are higher than budgeted and products, perhaps, have been sold at a loss.

Standard cost variances also give excellent trending information: companies can’t change the past but they can certainly influence the future. So, in an industry where items are manufactured repeatedly, standard costing may be the answer. But, when moving along the manufacturing spectrum from continuous process to job shop, it becomes less so.

Actual Costing

At the other end of the manufacturing spectrum are companies that manufacture, and sometimes even engineer, to order. Frequently, manufacturing volumes are low but the key thing is that these companies need to look at profitability by order, and not by batch as standard costing does.

When manufacturing against a contract, for example, they need to know exactly what the job has cost and that can’t be done easily with standard costing because the variances, at least for materials, will have been written away separately. The problem can be compounded in an ETO (engineer to order) environment when the customer requests design changes after production has commenced. Sometimes these changes result in the purchase of extra materials for which premium prices (or special delivery charges) have to be paid to ensure quick delivery. In these circumstances, there is no alternative to knowing exact (i.e. actual) costs.

Everything comes at a price though. If companies want to know exactly what a manufactured item has cost, they need first to know exactly what components, in terms of item and quantity, went into making it. But some companies have variable material usages. For example, waste can vary greatly in industries that use wood because wood is not uniform. The number (and distribution) of knot holes varies, so waste is only approximately predictable.

Material is only part of the problem. Labor and processing times can also vary; particularly if rework or rectification

work is required. So, to get accurate costs, it is necessary to measure, record and report actual usage of both materials and labor.

work is required. So, to get accurate costs, it is necessary to measure, record and report actual usage of both materials and labor.

This can be a problem in some industries that use bulk materials when the cost of those materials varies. Imagine that two batches of liquid are going into the same tank and those two batches have come in at different actual costs. When drawing liquid from the tank, it is impossible to know which batch is being used (in fact, it is almost certainly some of both). Luckily most ERP systems get around this problem by allowing the issue on a theoretical FIFO (first in, first out) basis, so the oldest batch is ‘assumed’ to have been used.

FIFO issues may not be a true reflection of reality, of course, but on the occasions when cost allocation to particular jobs has to be precise, ERP systems usually allow users to override this automatic selection and record a different batch. As the batches must have been of essentially identical material in order to have been mixed, it is of course generally irrelevant which was actually used. An exception would be when handling things like foodstuffs but, in these circumstances, if a batch of product is recalled because of a problem with an ingredient, it would be normal to also recall the product that theoretically used ingredients from batches either side of the suspect batch.

So, in a manufacturing environment where precise costings for each individual job or batch are essential, Actual (or FIFO) Costing is obviously more appropriate even though it is harder to identify trends that show up easily in Standard Costing. Be aware, though, that Actual or FIFO Costing tends to not work well in backflushing environments where material or labor variances are common, unless the ERP system chosen allows easy adjustment of resources used.

Annualreporting provides financial reporting narratives using IFRS keywords and terminology for free to students and others interested in financial reporting. The information provided on this website is for general information and educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice. Use at your own risk. Annualreporting is an independent website and it is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or in any other way associated with the IFRS Foundation. For official information concerning IFRS Standards, visit IFRS.org or the local representative in your jurisdiction.

Disclosure financial assets and liabilities

Introductory guidance

Disclosing financial assets and liabilities (financial instruments) in one note

Users of financial reports have indicated that they would like to be able to quickly access all of the information about the entity’s financial assets and liabilities in one location in the financial report. The notes are therefore structured such that financial items and non-financial items are discussed separately. However, this is not a mandatory requirement in the accounting standards.

Accounting policies, estimates and judgements

For readers of Financial Statements it is helpful if information about accounting policies that are specific to the entity

and about significant estimates and judgements is disclosed with the relevant line items, rather than in separate notes. However, this format is also not mandatory. For general commentary regarding the disclosures of accounting policies refer to note 25. Commentary about the disclosure of significant estimates and judgements is provided in note 11.

and about significant estimates and judgements is disclosed with the relevant line items, rather than in separate notes. However, this format is also not mandatory. For general commentary regarding the disclosures of accounting policies refer to note 25. Commentary about the disclosure of significant estimates and judgements is provided in note 11.

Scope of accounting standard for disclosure of financial instruments

IFRS 7 does not apply to the following items as they are not financial instruments as defined in paragraph 11 of IAS 32:

- prepayments made (right to receive future good or service, not cash or a financial asset)

- tax receivables and payables and similar items (statutory rights or obligations, not contractual), or

- contract liabilities (obligation to deliver good or service, not cash or financial asset).

While contract assets are also not financial assets, they are explicitly included in the scope of IFRS 7 for the purpose of the credit risk disclosures. Liabilities for sales returns and volume discounts (see note 7(f)) may be considered financial liabilities on the basis that they require payments to the customer. However, they should be excluded from financial liabilities if the arrangement is executory. the Reporting entity Plc determined this to be the case. [IFRS 7.5A]

Classification of preference shares

Preference shares must be analysed carefully to determine if they contain features that cause the instrument not to meet the definition of an equity instrument. If such shares meet the definition of equity, the entity may elect to carry them at FVOCI without recycling to profit or loss if not held for trading.

Reform of interest rate benchmarks

Certain interest rate benchmarks including LIBOR, EURIBOR and EONIA are being or have recently been reformed.

What are interest rate benchmarks?

Interest rate benchmark are used to determine

- the amount of interest payable for a wide range of financial products such as derivatives, bonds, loans, structured products and mortgages, and

- the valuation of financial products.

The most common examples of interest rate benchmarks used in financial contracts across the world are the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) and for the Euro, the Euro Interbank Offered Rate (EURIBOR) and Euro Overnight Index Average (EONIA).

Why are these benchmarks being reformed?

As benchmark rates are fundamental to so many financial contracts, they need to be robust, reliable and fit for purpose. Each of these interest rate benchmarks subject to reform were based on the rates at which banks lend to each other in the interbank market.

Financial regulatory authorities have expressed their concern that because interbank lending transactions have significantly decreased in recent years, the

benchmark rates may no longer be representative or reliable.

benchmark rates may no longer be representative or reliable.

This concern has resulted in recommendations made by the Financial Stability Board towards the global financial industry to reform the major interest rate benchmarks and to develop a set of alternative rates that are more representative of the current financial environment.

IFRS Reporting disclosure amendments

The amendments made to IFRS 9 Financial Instruments, IAS 39 Financial Instruments: Recognition and Measurement and IFRS 7 Financial Instruments: Disclosures provide certain reliefs in relation to interest rate benchmark reform. The reliefs relate to hedge accounting and have the effect that the reforms should not generally cause hedge accounting to terminate. However, any hedge ineffectiveness should continue to be recorded in the income statement. Given the pervasive nature of hedges involving interbank offered rates (IBOR)-based contracts, the reliefs will affect companies in all industries.

Entities relying on the relief must disclose:

- the significant interest rate benchmarks to which the entity’s hedging relationships are exposed

- the extent of the risk exposure that the entity manages that is directly affected by the interest rate benchmark reform

- how the entity is managing the process of transition to alternative benchmark rates

- a description of significant assumptions or judgements that the entity made in applying the reliefs, and

- the nominal amount of the hedging instruments in those hedging relationships. [IFRS 7.24H]

Information about how the entity is managing the transition process will provide users with an indication of the extent to which management is prepared for the transition. For example, this could include explanations about differences in fallback provisions between the hedged item and the hedging instruments.

The amendments are not clear whether the disclosure of the extent of the risk exposure that the entity manages could be provided on a qualitative rather than quantitative basis. However, numerical disclosures may be more useful for users.

Accounting policies relating to hedge accounting will need to be updated to reflect the reliefs. Fair value disclosures may also be impacted due to transfers between levels in the fair value hierarchy as markets become more / less liquid.

Entities should consider whether further disclosure of the impending replacement of IBOR should be provided in other parts of the annual report, for example in management’s discussion and analysis.

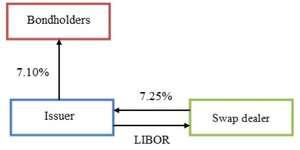

Example Disclosure reform of interest rate benchmarks

This Example Disclosure Related party transactions shows the disclosures an entity would have to add if it has a loan with an interest rate based on 3-month GPB LIBOR and a cash flow hedge in the form of a floating-to-fixed rate interest rate swap that is referenced to LIBOR. The disclosures assume that the entity has adopted the hedge accounting requirements of IFRS 9.

While primarily illustrating the disclosures required by the amendments made to IFRS 7 and other hedge accounting disclosures affected by IBOR reform, extracts

of other disclosures from the main body of the publication have been included, to provide some context for the additional disclosures.

of other disclosures from the main body of the publication have been included, to provide some context for the additional disclosures.

New or revised disclosures are highlighted with shading. This appendix does not illustrate disclosures that may be required if the terms of the loan and the swap have moved to new benchmark rates.

12 Financial risk management (extracts)

12(a) Derivatives (extracts)

(iv) Hedge effectiveness (extracts)

Hedge ineffectiveness for interest rate swaps is assessed using the same principles as for hedges of foreign currency purchases. It may occur due to:

- the credit value/debit value adjustment on the interest rate swaps which is not matched by the loan

- differences in critical terms between the interest rate swaps and loans, and

- the effects of the forthcoming reforms to GBP LIBOR, because these might take effect at a different time and have a different impact on the hedged item (the floating-rate debt) and the hedging instrument (the interest rate swap used to hedge the debt). Further details of these reforms are set out below. [IFRS 7.22B(c), IFRS 7.23D]

Ineffectiveness of CUXX,XXX has been recognised in relation to the interest rate swaps in other gains or losses in profit or loss for 2020 (2019 CUXX,XXX). The significant increase in ineffectiveness in the current year was caused by the expectation that the interest rate swap and the hedged debt will move from GBP LIBOR to SONIA at different dates. [IFRS 7.24C(b)(ii)]

12(b) Market risk

(ii) Cash flow and fair value interest rate risk

The group’s main interest rate risk arises from long-term borrowings with variable rates, which expose the group to cash flow interest rate risk. Group policy is to maintain at least 50% of its borrowings at fixed rate, using floating-to-fixed interest rate swaps to achieve this when necessary.

Generally, the group enters into long-term borrowings at floating rates and swaps them into fixed rates that are lower than those available if the group borrowed at fixed rates directly. During 2020 and 2019, the group’s borrowings at variable rate were mainly denominated in Oneland currency units and US dollars. Except for the GBP LIBOR floating rate debt noted below, other variable interest rates were not referenced to interbank offered rates (IBORs) that will be affected by the IBOR reforms. [IFRS7.22A(a),(b), IFRS7.33(a),(b)]

Included in the variable rate borrowings is a 10-year floating-rate debt of CU10,000,000 (2019 CU10,000,000) whose interest rate is based on 3 month GBP LIBOR. To hedge the variability of in cash flows of this loan, the group has entered into a 10-year interest rate swap with key terms (principal amount, payment dates, repricing dates, currency) that match those of the debt on which it pays a fixed rate and receives a variable rate. [IFRS 7.24H(a)]

The group’s borrowings and receivables are carried at amortised cost. The borrowings are periodically contractually repriced (see below) and to that extent are also exposed to the risk of future changes in market interest rates.

The exposure of the group’s borrowings to interest rate changes and the contractual re-pricing dates of the borrowings at the end of the reporting period are as follows: [IFRS 7.22A(c), IFRS 7.34(a), IFRS 7.24H(b)]

|

Amounts in CU’000 |

2020 |

%of total |

2019 |

% of total |

|

Variable rate borrowings – GBP LIBOR |

10,000 |

10% |

10,000 |

12% |

|

Variable rate borrowings – non-IBOR |

43,669 |

46% |

40,150 |

47% |

|

Fixed rate borrowings – repricing or maturity dates: |

||||

|

– Less than one year |

4,735 |

5% |

3,895 |

5% |

|

– 1 – 5 years |

26,626 |

27% |

19,550 |

23% |

|

– Over 5 years |

11,465 |

12% |

11,000 |

13% |

|

Total |

97,515 |

100% |

84,595 |

100% |

An analysis by maturities is provided in note 12(d) below. The percentage of total loans shows the proportion of loans that are currently at variable rates in relation to the total amount of borrowings.

Instruments used by the group

Swaps currently in place cover approximately 37% (2019 – 37%) of the variable loan principal outstanding. The fixed interest rates of the swaps range between 7.8% and 8.3% (2019 – 9.0% and 9.6%), and the variable rates of the loans are between 0.5% and 1.0% above the 90 day bank bill rate or LIBOR which, at the end of the reporting period, were 8.2% and x.x% respectively (2019 – 9.4% and x.x%). [IFRS 7.22B(a), IFRS 7.23B]

The swap contracts require settlement of net interest receivable or payable every 90 days. The settlement dates coincide with the dates on which interest is payable on the underlying debt. [IFRS 7.22B(a)]

Effects of hedge accounting on the financial position and performance

The effects of the interest rate swaps on the group’s financial position and performance are as follows:

|

Amounts in CU’000 |

2020 |

2019 |

|

Interest rate swaps |

||

|

Carrying amount (current and non-current asset) |

453 |

809 |

|

Notional amount – LIBOR based swaps [IFRS 7.24H(b),(e)] |

10,000 |

10,000 |

|

Maturity date [IFRS 7.23B(a)] |

2030 |

2030 |

|

1 : 1 |

1 : 1 |

|

|

Change in fair value of outstanding hedging instruments since 1 January [IFRS 7.24A(c)] |

xx |

xx |

|

Change in value of hedged item used to determine hedge effectiveness [IFRS 7.24B(b)(i)] |

xx |

xx |

|

Weighted average hedged rate for the year [IFRS 7.23B(b)] |

x.x% |

x.x% |

|

Notional amount – non-LIBOR based swaps [IFRS 7.24H(b),(e)] |

10,010 |

8,440 |

|

Maturity date [IFRS 7.23B(a)] |

2020 |

2019 |

|

Hedge ratio [IFRS 7.22B(c)] |

1 : 1 |

1 : 1 |

|

Change in fair value of outstanding hedging instruments since 1 January [IFRS 7.24A(c)] |

-202 |

1,005 |

|

Change in value of hedged item used to determine hedge effectiveness [IFRS 7.24B(b)(i)] |

202 |

1,005 |

|

Weighted average hedged rate for the year [IFRS 7.23B(b)] |

8.1% |

9. |

xx) Significant judgementsInterest rate benchmark reform Following the financial crisis, the reform and replacement of benchmark interest rates such as GBP LIBOR and other interbank offered rates (‘IBORs’) has become a priority for global regulators. There is currently uncertainty around the timing and precise nature of these changes. [IFRS 7.24H(b)] To transition existing contracts and agreements that reference GBP LIBOR to SONIA, adjustments for term differences and credit differences might need to be applied to SONIA, to enable the two benchmark rates to be economically equivalent on transition. Group treasury is managing the group’s GBP LIBOR transition plan. The greatest change will be amendments to the contractual terms of the GBP LIBOR-referenced floating-rate debt and the associated swap and the corresponding update of the hedge designation. However, the changed reference rate may also affect other systems, processes, risk and valuation models, as well as having tax and accounting implications. [IFRS 7.24H(c)] Relief appliedThe group has applied the following reliefs that were introduced by the amendments made to IFRS 9 Financial Instruments in September 2019:

Assumptions madeIn calculating the change in fair value attributable to the hedged risk of floating-rate debt, the group has made the following assumptions that reflect its current expectations:

|

Reform of interest rate benchmarks

Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks

Annualreporting provides financial reporting narratives using IFRS keywords and terminology for free to students and others interested in financial reporting. The information provided on this website is for general information and educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice. Use at your own risk. Annualreporting is an independent website and it is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or in any other way associated with the IFRS Foundation. For official information concerning IFRS Standards, visit IFRS.org or the local representative in your jurisdiction.

Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks Reform of interest rate benchmarks

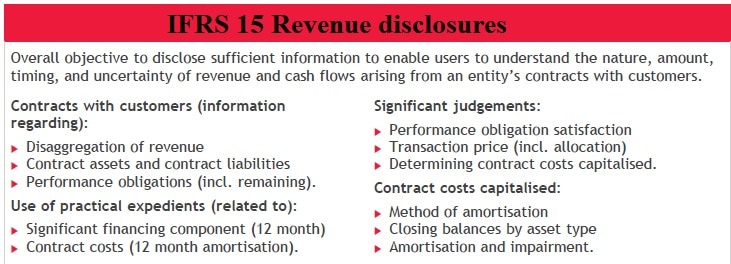

IFRS 15 Revenue Disclosures Examples

IFRS 15 Revenue Disclosures Examples provides the context of disclosure requirements in IFRS 15 Revenue from contracts with customers and a practical example disclosure note in the financial statements. However, as this publication is a reference tool, no disclosures have been removed based on materiality. Instead, illustrative disclosures for as many common scenarios as possible have been included.

Please note that the amounts disclosed in this publication are purely for illustrative purposes and may not be consistent throughout the example disclosure related party transactions.

Users of the financial statements should be given sufficient information to understand the nature, amount, timing and uncertainty of revenue and cash flows arising from contracts with customers. To achieve this, entities must provide qualitative and quantitative information about their contracts with customers, significant judgements made in applying IFRS 15 and any assets recognised from the costs to obtain or fulfil a contract with customers. [IFRS 15.110]

Disaggregation of revenue

[IFRS 15.114, IFRS 15.B87-B89]

Entities must disaggregate revenue from contracts with customers into categories that depict how the nature, amount, timing and uncertainty of revenue and cash flows are affected by economic factors. It will depend on the specific circumstances of each entity as to how much detail is disclosed. The Reporting entity Plc has determined that a disaggregation of revenue using existing segments and the timing of the transfer of goods or services (at a point in time vs over time) is adequate for its circumstances. However, this is a judgement and will not necessarily be appropriate for other entities.

Other categories that could be used as basis for disaggregation include:

- type of good or service (eg major product lines)

- geographical regions

- market or type of customer

- type of contract (eg fixed price vs time-and-materials contracts)

- contract duration (short-term vs long-term contracts), or

- sales channels (directly to customers vs wholesale).

When selecting categories for the disaggregation of revenue entities should also consider how their revenue is presented for other purposes, eg in earnings releases, annual reports or investor presentations and what information is regularly reviewed by the chief operating decision makers. [IFRS 15.B88]

Disclosure Related party transactions

– Learn how to do it –

Disclosure Related party transactions provides a summary of IFRS reporting requirements regarding IAS 24 Related party transactions and a possible disclosure schedule. However, as this publication is a reference tool, no disclosures have been removed based on materiality. Instead, illustrative disclosures for as many common scenarios as possible have been included. Please note that the amounts disclosed in this publication are purely for illustrative purposes and may not be consistent throughout the example disclosure related party transactions.

Presentation

All of the related party information required by IAS 24 that is relevant to the Reporting entity Plc has been presented, or referred to, in one note. This is considered to be a convenient and desirable method of presentation, but there is no requirement to present the information in this manner. Compliance with the standard could also be achieved by disclosing the information in relevant notes throughout the financial statements.

Materiality

The disclosures required by IAS 24 apply to the financial statements when the information is material. According to IAS 1 Presentation of Financial Statements,

materiality depends on the size and nature of an item. It may be necessary to treat an item or a group of items as material because of their nature, even if they would not be judged material on the basis of the amounts involved. This may apply when transactions occur between an entity and parties who have a fiduciary responsibility in relation to that entity, such as those transactions between the entity and its key management personnel. [IAS1.7]

materiality depends on the size and nature of an item. It may be necessary to treat an item or a group of items as material because of their nature, even if they would not be judged material on the basis of the amounts involved. This may apply when transactions occur between an entity and parties who have a fiduciary responsibility in relation to that entity, such as those transactions between the entity and its key management personnel. [IAS1.7]

Key management personnel compensation

While the disclosures under paragraph 17 of IAS 24 are subject to materiality, this must be determined based on both quantitative and qualitative factors. In general, it will not be appropriate to omit the aggregate compensation disclosures based on materiality. Whether it will be possible to satisfy the disclosure by reference to another document, such as a remuneration report, will depend on local regulation. IAS 24 itself does not specifically permit such cross-referencing.

Better Communication in Financial Reporting

Better Communication in Financial Reporting is an IFRS.org initiative to focus financial reporting on users. There is a general view that financial reports have become too complex and difficult to read and that financial reporting tends to focus more on compliance than communication. See also narrative reporting as a discussion on alternative ways of reporting.

At the same time, users’ tolerance for sifting through information to find what they need continues to decline.

This has implications for the reputation of companies who fail to keep pace. A global study confirmed this trend, with the majority of analysts stating that the quality of reporting directly influenced their opinion of the quality of management.

To demonstrate what companies could do to make their financial report more relevant, there are several suggestions to ‘streamline’ the financial statements to reflect some of the best practices that have been emerging globally over the past few years. In particular:

- Information is organized to clearly tell the story of financial performance and make critical information more prominent and easier to find.

- Additional information is included where it is important for an understanding of the performance of the company. For example, we have included a summary of significant transactions and events as the first note to the financial statements even though this is not a required disclosure.

Improving disclosure effectiveness

Terms such as ’disclosure overload’ and ‘cutting the clutter’, and more precisely ‘disclosure effectiveness’, describe a problem in financial reporting that has become a priority issue for the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB or Board), local standard setters, and regulatory bodies. The growth and complexity of financial statement disclosure is also drawing significant attention from financial statement preparers, and more importantly, the users of financial statements.

What happened in the reporting period

There is no requirement to disclose a summary of significant events and transactions that have affected the company’s financial position and performance during the period under review (or simply what happened in the reporting period). However, information such as this could help readers understand the entity’s performance and any changes to the entity’s financial position during the year and make it easier finding the relevant information. However, information such as this could also be provided in the (unaudited) operating and financial review rather than the (audited) notes to the financial statements.

Covid-19

At the time of writing, the biggest impact on the financial statements of entities all around the world is related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Most entities will be affected by this in one form or another and should discuss the impact prominently in their financial statements. However, as the events are still unfolding, this publication is not providing any illustrative examples or guidance. See how to account for Covid-19 to get an up-to-date discussion.

Going concern disclosures [IAS1.25]

When preparing financial statements, management shall make an assessment of an entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. Financial statements shall be prepared on a going concern basis unless management either intends to liquidate the entity or to cease trading, or has no realistic alternative but to do so.

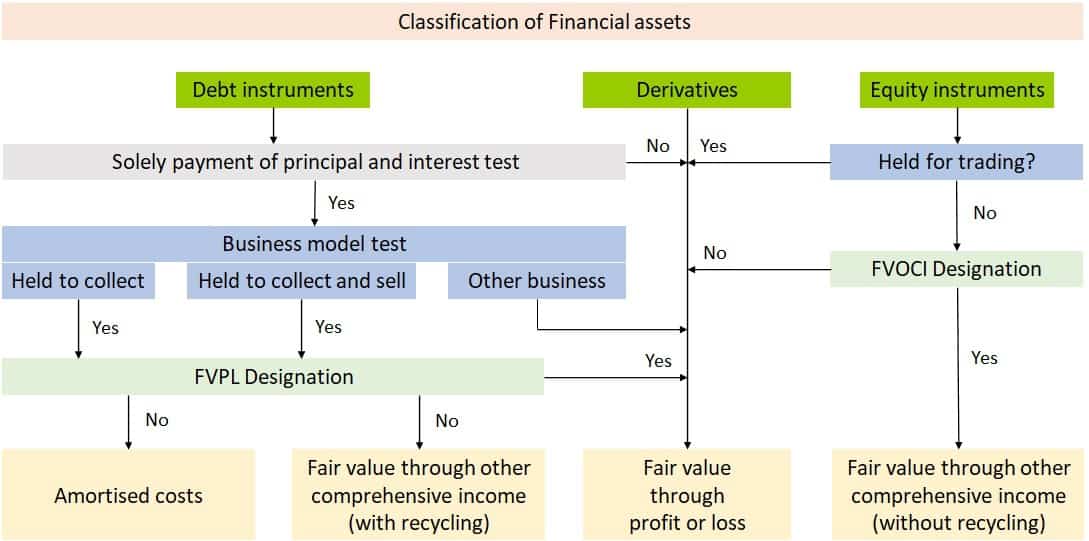

The SPPI Test

If an asset is in a hold-to-collect or hold-to-collect or sell business model, an entity assesses whether the cash flows from the financial asset meet the ‘solely payments of principal and interest’ (SPPI Test) benchmark – i.e. whether the contractual terms of the financial asset give rise, on specified dates, to cash flows that are solely payments of principal and interest.

- ‘Principal’ is the fair value of the financial asset on initial recognition. The principal may change over time – e.g. if there are repayments of principal.

- ‘Interest’ is consideration for the time value of money and credit risk. Interest can also include consideration for other basic lending risks and costs, and a profit margin.

A financial asset that does not meet the SPPI Test is always measured at FVPL, unless it is a non-trading equity instrument and the entity makes an irrevocable election to measure it at FVOCI. Here is the decision tree to put the narrative in context:

Contractual cash flows that meet the SPPI Test are consistent with a basic lending arrangement in the banking industry.

Sale with a right of return in IFRS 15

Under IFRS 15 Revenue from contract with customers, when an entity makes a sale with a right of return it recognises revenue at the amount to which it expects to be entitled by applying the variable consideration and constraint guidance set out in Step 3 of the model (see Step 3 Determine the transaction price). The entity also recognises a refund liability and an asset for any goods or services that it expects to be returned.

- An entity applies the accounting guidance for a sale with a right of return when a customer has a right to:

a full or partial refund of any consideration paid; - a credit that can be applied against amounts owed, or that will be owed, to the entity; or

- another product in exchange (unless it is another product of the same type, quality, condition and price – e.g. exchanging a red sweater for a white sweater). [IFRS 15.B20]

An entity does not account for its stand-ready obligation to accept returns as a performance obligation. [IFRS 15.B21–B22]

In addition to product returns, the guidance also applies to services that are provided subject to a refund.

The guidance does not apply to:

- exchanges by customers of one product for another of the same type, quality, condition and price; and

- returns of faulty goods or replacements, which are instead evaluated under the guidance on warranties. [IFRS 15.B26–B27]

When an entity makes a sale with a right of return, it initially recognises the following: [IFRS 15.B21, B23, B25]

Licensing of intellectual property – in summary

The standard provides application guidance for the recognition of revenue attributable to a distinct licence of intellectual property (IP).

The general model is that if the licence is distinct from the other goods or services, then an entity assesses the nature of the licence to determine whether to recognise revenue allocated to the licence at a point in time or over time and to estimate variable consideration.

But with complex topics like licensing of intellectual property, there is also guidance separate from the general model for estimating variable consideration, on the recognition of sales- or usage-based royalties on licences of IP when the licence is the sole or predominant item to which the royalty relates.

What is intellectual property?

One could say almost everything could be intellectual property! Licensing of intellectual property

Here is a description (not a definition!) from the WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organisation):

Intellectual property (IP) refers to creations of the mind, such as inventions; literary and artistic works; designs; and symbols, names and images used in commerce.

IP is in general protected in law by, for example, patents, copyright and trademarks, which enable people to earn recognition or financial benefit from what they invent or create. A difficult balance exists between striking the interests of innovators and the wider public interest, businesses operating in IP have to foster an environment in which creativity and innovation can flourish.

Just take a look at the (public) discussion between open source software (Apache OpenOffice) and licensed software (Microsoft Office365).