IFRS 10 Special control approach determines which entities are consolidated in a parent’s financial statements and therefore affects a group’s reported results, cash flows and financial position – and the activities that are ‘on’ and ‘off’ the group’s balance sheet. Under IFRS, this control assessment is accounted for in accordance with IFRS 10 ‘Consolidated financial statements’.

Some of the challenges of applying the IFRS 10 Special control approach include:

- identifying the investee’s returns, which in turn involves identifying its assets and liabilities. This may appear straightforward but complications arise when the legal ownership of assets diverges from the accounting depiction (for example, in financial asset transfers that ‘fail’ de-recognition, and in finance leases). In general, the assessment of the investee’s assets and returns should be consistent with the accounting depiction in accordance with IFRS

- it may not always be clear whether contracts and other arrangements between an investor and an investee

- create rights or exposure to a variable return from the investee’s performance for the investor; or

- transfer risk or variability from the investor to the investee IFRS 10 Special control approach

- the relevant activities of an SPE may not be obvious, especially when its activities have been narrowly specified in its purpose and design IFRS 10 Special control approach

- the rights to direct those activities might also be difficult to identify, because for example, they arise only in particular circumstances or from contracts that are outside the legal boundary of the SPE (but closely related to its activities).

IFRS 10 Special control approach sets out requirements for how to apply the control principle in less straight forward circumstances, which are detailed below: IFRS 10 Special control approach

- when voting rights or similar rights give an investor power, including situations where the investor holds less than a majority of voting rights and in circumstances involving potential voting rights

- when an investee is designed so that voting rights are not the dominant factor in deciding who controls the investee, such as when any voting rights relate to administrative tasks only and the relevant activities are directed by means of contractual arrangements IFRS 10 Special control approach

- involving agency relationships IFRS 10 Special control approach

- when the investor has control only over specified assets of an investee

- franchises. IFRS 10 Special control approach

Majority holdings in an investee

IFRS 10 confirms that an investor with the majority of an investee’s voting rights controls an investee in most circumstances. In the absence of other relevant factors the majority vote holder has control if:

- the investee’s relevant activities are directed by the holder of the majority of the voting rights; or

- the majority of the members of the governing body that directs the relevant activities is appointed by a vote of the holder of the majority of the voting rights [IFRS 10.B35].

IFRS 10 has more specific guidance on when the majority owner does not have control in the following situations:

|

Case |

Examples |

|

Another entity that is not an agent has rights to direct relevant activities |

Another investor’s voting rights, plus its substantive potential voting rights, represent an overall majority of voting power [IFRS 10.B36] Investee’s relevant activities are subject to direction by:

|

|

Voting rights are not substantive |

When different factors are considered more weight is given to the evidence in the first row above. |

Involvement of a government, court, administrator (or similar) or regulator in an investee’s decision-making process does not necessarily mean that a majority owner does not have control. Careful consideration of all facts and circumstances is necessary and judgement may be required. IFRS 10 Special control approach

The following example describes one such scenario and the required analysis:

|

Example – Scheme of protection from creditors |

|

In country X, a legislative mechanism exists whereby a ‘sick’ company is able to seek statutory protection from its creditors in order to provide a period of time for restructuring and rehabilitation. Key features of Country X’s applicable law are that:

Reasoning: In this situation a majority owner retains the right to appoint the majority of the board of directors, but the board’s powers are constrained by the Restructuring Board’s and operating agent’s ability to:

Deciding whether a majority owner has retained or loses control involves determining which activities have the greatest expected effect on returns. For a company in financial distress, the restructuring activity might affect returns more than day-to-day operations. In particular, without such restructuring the company may be forced to enter liquidation in which case returns to shareholders are often zero. However, reaching a conclusion involves careful consideration of all facts and circumstances and may require judgement. |

Large minority holdings in an investee

IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach

While control assessments involving majority ownership are relatively straightforward, IFRS 10 requires more focus on investees in which the investor holds a significant minority of voting rights. This is because, under IFRS 10, control exists when the investor has the practical ability to direct an investee’s relevant activities. This approach is often referred to an effective (or de facto) control model. IFRS 10 Special control approach

This section discusses basic situations in which minority voting rights may confer control in isolation – ie in the absence of potential voting rights, other contractual rights or other relevant facts and circumstances. In practice, all these factors need to be considered collectively to reach a conclusion. IFRS 10 Special control approach

In practice IFRS 10 Special control approach

To illustrate a de facto control approach, and how it differs from a legal control model, consider this example below:

|

Example – Large minority shareholding |

|

An investor holds 47% of the ordinary shares in an investee with a conventional control and governance structure (in others words, an investee whose relevant activities are directed by voting rights conferred by ordinary shares). The remaining 53% of the shares are owned by hundreds of other unrelated investors, none of whom own more than 1% individually. There are no arrangements for the other shareholders to consult one another or act collectively and past experience indicates that few of the other owners actually exercise their voting rights at all. Reasoning: Under the practical ability model in IFRS 10, the investor controls the investee. This is because its voting power is sufficient to provide the practical ability to direct. A large number of other shareholders would have to act collectively to outvote the investor. There are no mechanisms in place to facilitate collective action. |

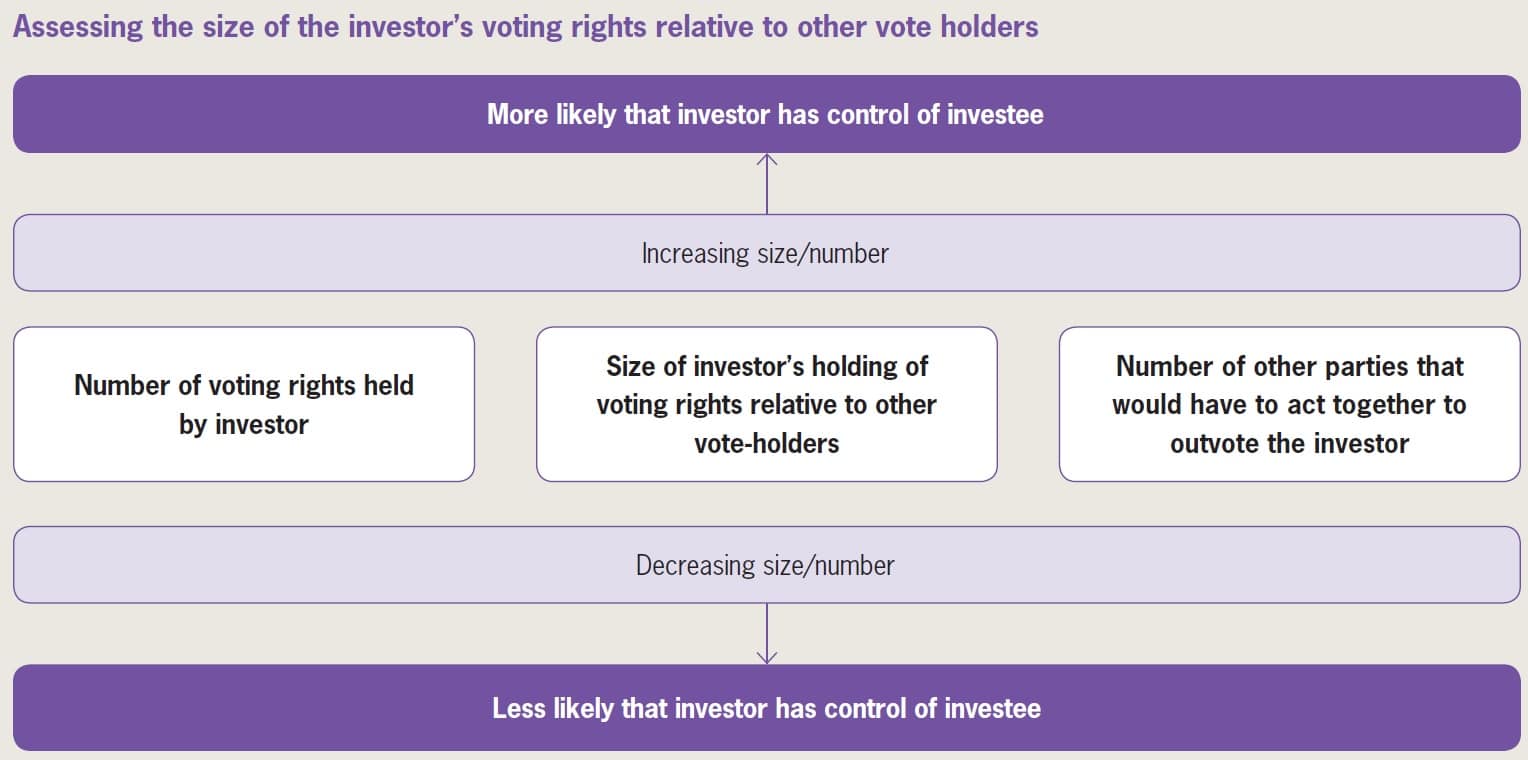

The preceding example is a relatively clear-cut situation in which a large minority shareholding confers control based solely on an analysis of the distribution of voting power. In assessing whether an investor’s voting rights are sufficient to give it power an investor considers all facts and circumstances, including:

- the size of the investor’s holding of voting rights relative to other vote holders, noting that:

- the more voting rights an investor holds, the more likely the investor is to have power

- the more voting rights an investor holds relative to other vote holders, the more likely it is to have power

- the greater the number of other parties that would need to act together to outvote the investor, the greater the likelihood the investor has power IFRS 10 Special control approach

- potential voting rights held by the investor and other parties

- other contractual rights IFRS 10 Special control approach

- any additional facts and circumstances that indicate the investor has, or does not have, the current ability to direct the relevant activities at the time that decisions need to be made, including voting patterns at previous shareholders’ meetings [IFRS 10.B42]. IFRS 10 Special control approach

Although IFRS 10 has no bright lines on when a particular distribution of voting power confers control, our example above and the following two examples below are based on similar examples in IFRS 10 and therefore serve to illustrate the IASB’s thinking: IFRS 10 Special control approach

|

Example – Two other shareholders could outvote Investor |

|

Investor A holds 45% of the voting rights of an investee. Two other investors each hold 26% of the voting rights of this investee. The remaining voting rights are held by three other shareholders, each holding 1%. There are no other arrangements that affect decision-making. Reasoning: In this case, the absolute size of investor A’s voting interest, and its size relative to the other shareholdings, are sufficient to conclude that investor A does not have control. The two investors holding 26% could readily co-operate to outvote Investor A. |

|

Example – Eleven other shareholders could outvote Investor |

|

Investor A holds 45% of the voting rights of an investee. Eleven other shareholders each hold 5% of the voting rights of the investee. None of the shareholders has contractual arrangements to consult any of the others or make collective decisions. Reasoning: Based on IFRS 10’s guidance, the distribution of voting rights is inconclusive. Other facts and circumstances should be considered to assess whether Investor A has control. |

Accordingly IFRS 10 makes it clear that a large minority shareholder in extreme:

- has control when hundreds or thousands of other shareholders would have to act collectively to outvote it (and there is no mechanism to facilitate collective action), and IFRS 10 Special control approach

- does not have control if only two other shareholders could act collectively to outvote it.

However, many situations are less clear-cut and an analysis of the distribution of voting rights (along with any other contractual rights and potential voting rights) is inconclusive. The previous example above shows one such case, in which eleven other shareholders could collectively outvote the investor. IFRS 10 Special control approach

Additional facts and circumstances then need to be considered – and judgement may be required. IFRS 10 does not specify any bright lines or thresholds to determine when an analysis of distribution of voting rights is sufficient to reach a conclusion and when additional facts and circumstances must also be considered. IFRS 10 Special control approach

As noted above, one of the important other factors is the voting pattern of other shareholders at previous shareholders’ meetings. This is illustrated in the example below: IFRS 10 Special control approach

|

Example – Shareholder participation |

|

An investor holds 35% of the voting rights of an investee. Three other shareholders each hold 5% of the voting rights of the investee. The remaining 50% of the voting rights are held by numerous other shareholders, none individually holding more than 1%. None of the shareholders has arrangements to consult any of the others or make collective decisions. Decisions about the relevant activities are directed by a simple majority of the votes cast at shareholders’ meetings. At recent meetings, 75% of the total voting rights have been cast (including the investor’s votes). Reasoning: In this case, the absolute size of investor A’s voting Based on IFRS 10’s guidance, the investor does not have control. The active participation of the other shareholders at recent shareholders’ meetings indicates that the investor would not have the practical ability to direct the relevant activities unilaterally. The fact that other shareholders may have voted in the same way as the investor, with the effect that the investor’s desired outcomes have been achieved, does not change the conclusion. |

This example makes the important point that an ability to direct as a result of other vote-holders choosing to vote in the same way does not amount to control by itself. This is because the decisions are not being taken unilaterally by one investor. That said, although the above example might seem to set a clear threshold, some In practice questions can be expected in practice. IFRS 10 Special control approach

These include: IFRS 10 Special control approach

- how far back an investor should look when assessing past voting behaviour

- whether it is appropriate to assume that past behaviour trends will continue (for example, it is possible that other shareholders’ voting behaviour will be altered by another investor acquiring a major holding)

- situations in which past data is not available such as start-ups and some newly acquired holdings.

There is no single right answer to these questions that will apply in all situations. However, in our view the judgement required is essentially forward-looking. The key question for an investor with a large minority holding is whether, based on the best information available, it reasonably expects to have the practical ability to direct the investee’s relevant activities unilaterally going forward. IFRS 10 Special control approach

Another In practice issue is the role of additional expertise and ‘soft’ influence in a de facto control assessment. This is illustrated in the example below: IFRS 10 Special control approach

|

Example – Different levels of knowledge and expertise |

|

Investor A, an entity operating in a high technology industry, establishes a new venture in an overseas jurisdiction. The corporate law in this jurisdiction prohibits majority foreign ownership. Accordingly, Investor A identifies a local partner (B) to co-invest. Ownership and voting rights are split 49% and 51% between the investor and local partner. The new venture’s Board comprises five directors of which Investor A is entitled to appoint two and local partner B three. All relevant activities are directed by the Board. However, because the Investor A has superior industry knowledge, the local investor agrees to an initial Board comprising four current employees of Investor A and only one representative of its own. Although the composition of the Board can be changed at future meetings, Investor A expects that it will in practice be able to continue to appoint the majority of the Board because of its superior industry knowledge and expertise. Reasoning: IFRS 10 has no specific guidance on the ability to direct through additional knowledge and expertise. IFRS 10 does however include various other ‘indicators’ and ‘evidence’ to assist in more difficult assessments. Some of this guidance may suggest that Investor A does have control in this example. The following are non-conclusive indicators:

If it would be impractical for the local partner B to oppose the wishes of Investor A there is an argument that B’s rights are not substantive. For example, depending on the type of technology involved and the local market, Investor A might be the only feasible source of suitably qualified people. In that case it is likely that Investor A has control. However, if local partner B has the practical ability to exercise its rights then Investor A does not have control. This is because Investor A’s past ability to appoint the majority of the Board is not unilateral, but exists only with the consent of local partner B. This consent can be withdrawn unilaterally. The first and second indicators above would not change the analysis because the basic voting arrangements lead to a clear conclusion. |

|

Unclear control assessment = No control |

Importantly, IFRS 10 states that if the assessment remains unclear having considered all the applicable guidance, the investor does not have control [IFRS 10.B46]. IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach |

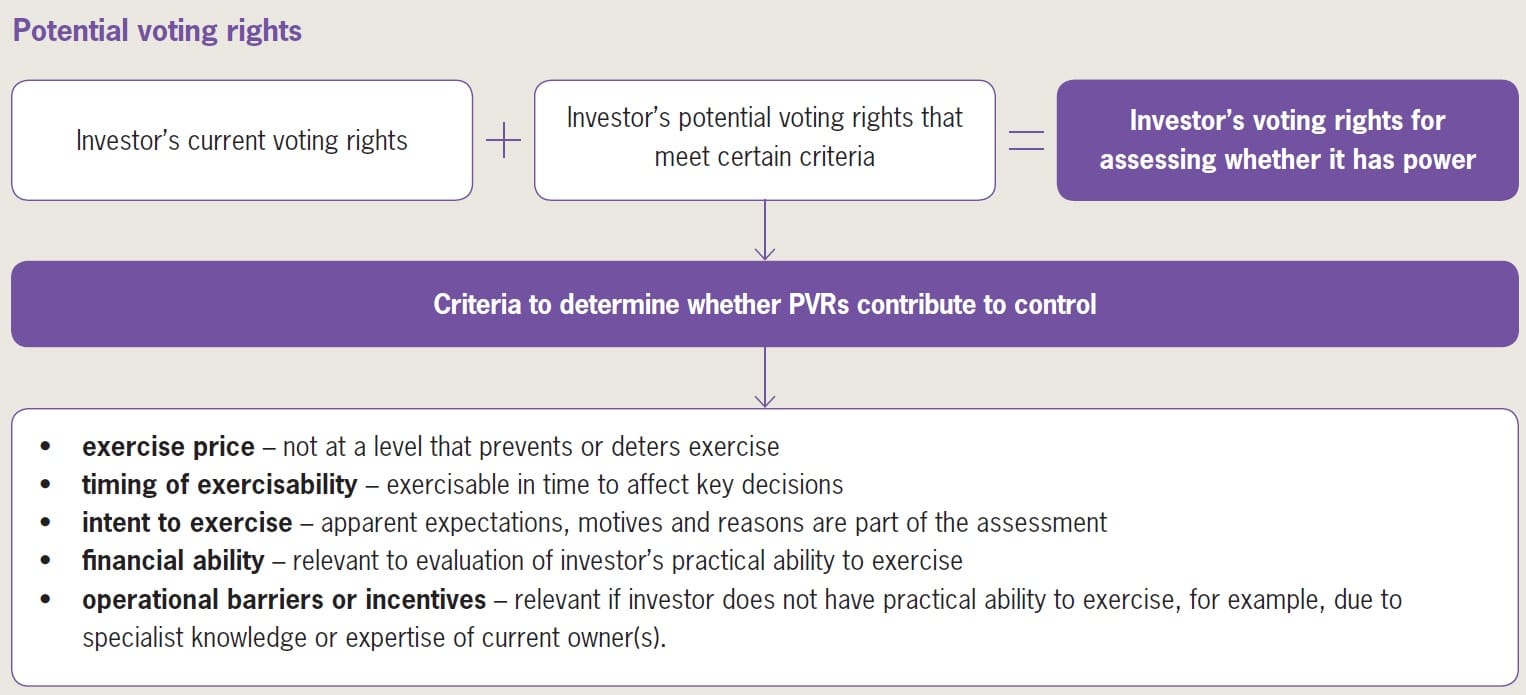

Potential voting rights

IFRS 10 Special control approach

An investor may hold instruments that (if exercised or converted), give the investor power to direct the relevant activities. These are called ‘potential voting rights’ and may be held through ownership of the following types of instrument:

- share options and warrants IFRS 10 Special control approach

- convertible bonds IFRS 10 Special control approach

- convertible preference shares. IFRS 10 Special control approach

Potential voting rights can contribute to control of an investee in combination with current voting rights, or even confer control on their own. However, IFRS 10 requires an assessment to determine whether potential voting rights are substantive.

IFRS 10 has no bright lines and so judgement will be required.

IFRS 10’s ‘substantive’ assessment takes into account both:

- the general guidance in IFRS 10.B22-B25 – summarised in the elements of control

- the purpose and design of the instrument – including its terms and conditions, and the investor’s apparent expectations, motives and reasons for agreeing to them [IFRS 10.B48].

Some of the factors referred to in IFRS 10.B22-B25 are normally more relevant than others, although any could be relevant in some situations. The following model summarises the factors that are most commonly of practical relevance:

In practice

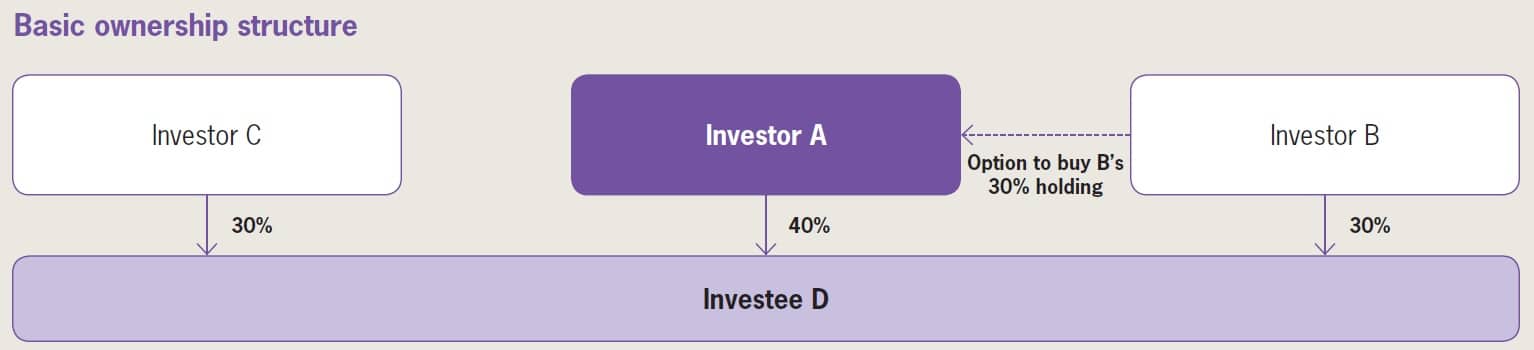

The In practice of IFRS 10’s approach is best illustrated using examples. The examples in this section draw on the basic ownership structure in the flowchart below. Each example also assumes that Investee D is controlled by shareholder vote, and that there are no contractual or other non-voting rights that affect the analysis:

The following examples are based on the general fact pattern above, with different specific detailed circumstances to illustrate the following different factors in the analysis. While each example focuses on one aspect of the analysis, it should be noted that IFRS 10 requires a broad assessment of whether a right is substantive. Accordingly, none of the individual factors discussed below is normally decisive in isolation.

|

Example – Exercise price somewhat out-of-the-money |

|

Investor A’s option has been acquired recently and is exercisable at any time in the next two years. The exercise price is fixed. The fixed price exceeds the current fair value of the underlying shares by 30%. Reasoning: In accordance with IFRS 10 Investor A considers, among other things, whether the exercise price presents a barrier or deterrent. In this case, a 30% premium is not trivial. However, this premium may or may not prevent the option from being substantive in practice. Investor A should consider additional factors such as:

|

|

Example – Option not yet exercisable |

|

Investor A’s option has been acquired recently and is exercisable in 30 days’ time and then at any time in the following 12 months. The exercise price is based on a formula that is designed to approximate fair value of the underlying shares at each exercise date. An annual shareholders’ meeting is scheduled in six months’ time. Any existing shareholder is also able to call a special meeting, on giving 45 days’ notice to other shareholders. Members of the management committee (which directs Investee D’s relevant activities) are elected or removed at these meetings by a simple majority of shareholder votes cast. Reasoning: To be substantive in accordance with IFRS 10 a right must confer the current ability to direct relevant activities. However, while this normally requires the right to be currently exercisable, IFRS 10 explains that this is not always the case. Instead, the key question is whether the rights can be exercised by the time the decisions need to be taken. When direction is by shareholder voting, this means that potential voting rights must be convertible into current voting rights before the next voting opportunity. In this case, the potential voting rights are convertible in time because Investor A can call a meeting in 45 days and exercise the option in 30 days. No other shareholder can force a vote before the option’s earliest exercise date. Variation 1 – longer exercise date: Assume instead that the option becomes exercisable 60 days after purchase. The notice period required for a shareholder vote is still 45 days. In this case, for IFRS 10 purposes, the option would not be substantive on purchase. However, it may become so 15 days later. Variation 2 – staggered exercise dates: Assume the option can be exercised only on fixed dates, at 90 day intervals, over the next 720 days. The notice period required for a shareholder vote is still 45 days. This fact pattern presents a practical difficulty. Taking IFRS 10’s guidance at face value would imply that Investor A could obtain control 45 days after acquiring the option, but then lose control in another 45 days (ie on day 90) if it doesn’t exercise the option. This pattern is then repeated. Although it is of course possible to obtain and lose control of an investee repeatedly in a short period, this outcome is counter-intuitive and unlikely to represent the substance of the arrangement in this example. It is important to consider IFRS 10’s guidance on timing of exercisability in the context of the broader principle and guidance on ‘substantive’, rather than take an entirely mechanistic approach. In this example, if Investor A does conclude that it has control of Investee D from day 45 we doubt it is appropriate to reverse this conclusion in the event of non-exercise on day 90 (provided the other relevant factors support the control conclusion). Although it may in theory be possible for Investors B and C to call a meeting in the next 45 days, and outvote Investor A, they may have little incentive to do this in the circumstances. In reaching a conclusion, assessing the purpose and design of the option, and the parties’ intentions and motivations for agreeing to its terms, will be particularly important. |

The Standard itself includes some other examples illustrating its guidance on timing of exercisability [Illustrative Examples 3–3D of IFRS 10.B24]. IFRS 10 Special control approach

|

Example – Option held for defensive purposes |

|

As in the preceeding example, Investor A’s option is exercisable at any time in the next two years at a fixed exercise price that exceeds the current estimated fair value of the underlying shares by 30%. However, Investor A’s intention in purchasing this option was not to obtain control of Investee D, but instead to prevent Investor B from obtaining control by acquiring Investor C’s shares. Investor A would be prepared to exercise, and pay the required premium, to block Investor B but is otherwise content to remain a long-term strategic (but non-controlling) investor. Reasoning: In accordance with IFRS 10 Investor A considers, among other things ‘the purpose and design’ of the instrument, as well as the purpose and design of any other involvement the investor has with the investee. This includes an assessment of the various terms and conditions of the instrument as well as the investor’s apparent expectations, motives and reasons for agreeing to those terms and conditions [IFRS 10.B48]. If the evidence supports Investor A’s assertion that the potential voting rights are intended solely as a defensive mechanism, and would be exercised only in particular circumstances, it is reasonable to conclude that the rights are non-substantive. |

Special purpose and structured entities

IFRS 10 Special control approach

IFRS 10 applies to both normal and structured or special purpose entities (SPEs). IFRS 10 has no specific guidance on SPEs. The reasons for referring to SPEs in this guide are that: IFRS 10 Special control approach

- the term is widely-used in practice to describe certain types of entity (see below)

- many of the approaches used for assessing control of SPEs under the old guidance in SIC-12 are not sufficient or appropriate under IFRS 10. IFRS 10 Special control approach

An SPE is not defined in IFRS nor was it defined in SIC-12. The latter simply noted that ‘an entity may be created to accomplish a narrow and well-defined objective (for example, to effect a lease, research and development activities or securitisation of financial assets)’. This lack of a clear definition (and consequent lack of a clear dividing line as to which entities SIC-12 applied to) was a perceived shortcoming of IAS 27 (2008) and SIC-12.

Despite the lack of a definition, entities typically considered to be SPEs in practice normally have some of the characteristics noted in the Food for thought box below. IFRS 10 Special control approach

|

Food for thought – Typical features of SPEs |

|

The most widespread use of SPEs is in the financial services industry, in connection with securitisation and other asset-backed financing arrangements. Other common uses include:

Typically, an SPE has at least some of the following governance characteristics:

|

The practical implications of IFRS’s 10’s control definition on SPE’s are as follows:

- SPE control assessments are in the scope of IFRS 10’s single model

- IFRS 10 includes guidance on investees for which voting rights cannot significantly affect the returns and contractual rights determine the direction of the relevant activities IFRS 10 Special control approach

- SIC-12 was applied in different ways by different entities and some approaches was longer sufficient, for example, assessments based only on: IFRS 10 Special control approach

- quantitative analysis of risks and rewards IFRS 10 Special control approach

- qualitative consideration of whether an SPE’s activities are conducted on behalf of the investor and the activities are on ‘autopilot’. IFRS 10 Special control approach

Although IFRS 10 has no separate guidance on SPEs, it does have guidance on assessing control over entities for which voting rights do not have a significant effect on returns. This type of entity is described (in IFRS 12) as a ‘structured entity’. In practice, we expect that most (but not all) SPEs previously within the scope of SIC-12 would be structured entities under IFRS 12’s definitions.

Definition of structured entity [IFRS 12 Appendix A]

An entity that has been designed so that voting or similar rights are not the dominant factor in deciding who controls the entity, such as when any voting rights relate to administrative tasks only and the relevant activities are directed by means of contractual arrangements.

IFRS 10’s guidance on assessing control over these types of entity is summarised in the table below [IFRS 10.B51-B54]:

|

Criterion |

Explanation |

|

Consider investor’s involvement in ‘purpose and design’ of investee IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach |

|

|

Consider contractual arrangements between investor and investee IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach |

|

|

Relevant activities may include activities that arise only in particular circumstance IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach |

|

|

Consider implicit and explicit commitments to support investee IFRS 10 Special control approach |

|

|

assessment of the investee’s relevant activities and the investor’s rights to decide about them |

In overview, then, applying IFRS 10 to structured entities and SPEs requires a detailed and specific assessment of the investee’s relevant activities and the investor’s rights to make decisions about them. |

|

Food for thought – Link with financial asset derecognition rules |

|

SPEs are often used in connection with securitisations and other transactions involving a transfer of financial assets. The financial reporting impact of these transactions depends on the derecognition requirements in IFRS 9 ‘Financial Instruments’ as well as the consolidation conclusion under IFRS 10. IFRS 10 Special control approach If the asset transfer ‘fails’ de-recognition because the transferor retains substantially all the risks and rewards of the transferred assets, the accounting effect is often very similar to consolidation of the SPE. |

|

Example – Investment vehicle |

|

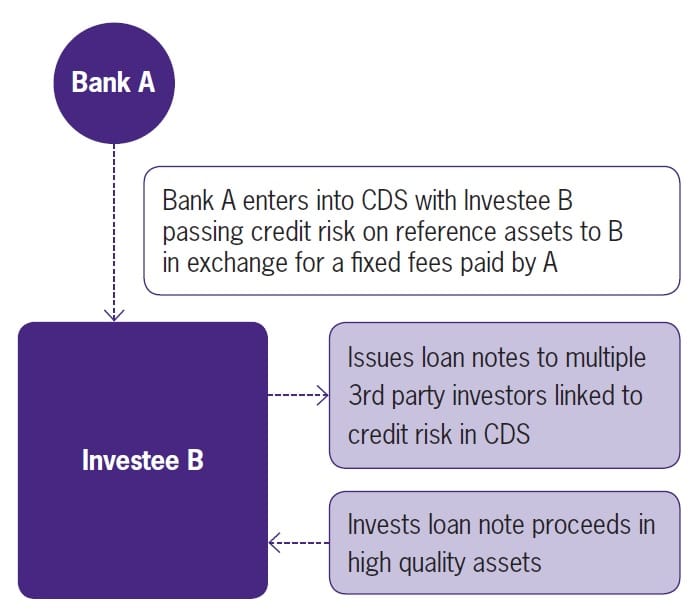

Bank A wishes to provide investment opportunities to outside investors wishing to assume credit risks associated with specific reference assets. It establishes an entity, Investee B, and passes the credit risk to it by writing a credit default swap (CDS). Investee B issues loan notes with payments that are contractually linked to the credit risk on these reference assets. The loan notes are purchased by multiple, unrelated investors. Investee B uses the proceeds to purchase high quality assets that will serve as collateral. Neither Bank A nor any of the note holders have voting rights in Investee B. The structure can be summarised as follows:

Reasoning: Further analysis is required to determine whether or not Bank A controls Investee B in accordance with IFRS 10, including careful consideration of Investee B’s purpose and design – in particular:

|

The following example illustrates, among other points, a situation in which decision-making rights that are relevant to the analysis lie outside the legal boundary of an investee: IFRS 10 Special control approach

|

Example – ‘OpCo/PropCo’ structure |

|

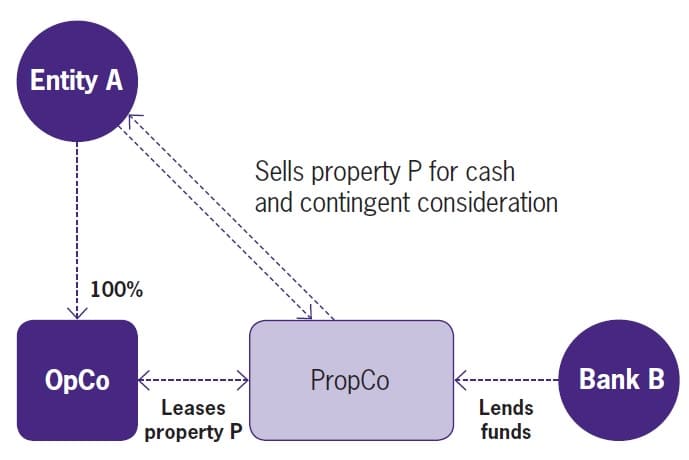

Entity A, a commercial business with extensive property holdings, wishes to reduce its property exposure and obtain finance on advantageous terms. It sets up an ‘OpCo/PropCo’ structure involving two new entities. The trade and operating assets of one of its businesses are transferred into ‘OpCo’, which is a conventional entity and is wholly-owned by Entity A. One property (P) used in this business is sold to ‘PropCo’. PropCo pays cash and contingent consideration (see below). The cash payment is financed by a mortgage loan to PropCo from Bank B. Property P is leased by OpCo under an operating lease. The lease requires OpCo to bear all of the property costs (including maintenance, capital expenditures, tax and insurance). PropCo’s only role is to collect rent and pay the interest and principal on the debt. The arrangements made at set-up include options for OpCo to extend its lease and for Entity A to repurchase the property at market value. In the event of default or non-renewal/repurchase, Property P will be sold on the market to enable PropCo’s loans to be repaid. Any excess funds are remitted to Entity A as additional consideration for the original sale.

Analysis: In this fact pattern both Entity A’s group (including its OpCo subsidiary) and Bank B have rights and exposure to variable returns from Property P. Entity A (including its OpCo subsidiary) has exclusive use of the property, as well as rights from the contingent consideration. Bank B has rights and exposure to variable returns as a result of the credit risk in its loan to PropCo. Also, both Entity A and Bank B have some decision-making rights that are relevant to the analysis:

It is likely in this scenario that Entity A controls PropCo. Entity A has more rights and exposure than Bank B (which is expected to receive a lender’s return), and its decisions to renew the lease or purchase the asset are expected to have a greater impact on PropCo’s returns. In addition, an evaluation of PropCo’s purpose and design may indicate that PropCo is designed to enable Entity A to raise finance using Property P as security, retaining rights over the key decisions. |

The variation to this fact pattern below illustrates the importance of identifying the assets of an SPE in accordance with the substance and accounting depiction of an arrangement, rather than looking solely at legal ownership:

|

Example – ‘OpCo/PropCo’ structure – variation #1 |

|

The facts are similar to the ‘OpCo/PropCo’ structure above except that:

Reasoning: This changes the analysis primarily because PropCo’s assets no longer include Property P (because, from an IFRS perspective, the property is leased to OpCo under a finance lease). PropCo’s main asset is now a finance lease receivable. Entity A (including OpCo) has a finance lease obligation to PropCo. An obligation to an investee does not create rights or exposure to variable returns for the investor – instead this transfers variability to the investee. Accordingly, Entity A does not control PropCo. Entity A would however include the property and finance lease liability in its financial statements in accordance with IFRS 16 ‘Leases’. |

The second variation below introduces additional decision-making rights, some of which are shared rights and some unilateral. In this situation the identification of the relevant activities, and whether the related decisions are taken jointly or unilaterally, becomes critical:

|

Example – ‘OpCo/PropCo’ structure – variation #2 |

|

Facts are similar to the ‘OpCo/PropCo’ structure above except that:

Reasoning: In this variation Entity A (including OpCo), Investor C and Bank B have rights or exposure to variable returns. Entity A and Bank B hold some decision-making rights unilaterally (as in the ‘OpCo/PropCo’ structure above). However, PropCo now has a wider range of activities concerning future property deals and financings, and the related decisions are directed jointly by Entity A and Investor C. If these wider activities are determined to be the relevant activities (which is likely) then PropCo is a joint arrangement within the scope of IFRS 11 because Entity A and Investor C have joint control. |

Principal-agent situations

IFRS 10 Special control approach

As explained in the ‘Ability to use power to affect returns‘, IFRS 10 includes extensive guidance on situations in which an entity with decision-making rights over an investee is an agent or a principal. An agent is an entity primarily engaged to act in the best interests of the other parties (ie the principals) in exercising its rights. An investor that has rights to direct an investee’s relevant activities as an agent does not meet the ‘linkage’ element of the control definition.

|

Food for thought – When is the principal-agent assessment relevant? |

|

In practice the principal-agent assessment is relevant only when an investor:

Accordingly, an assessment is not needed when it is clear that:

The examples in IFRS 10 discuss the role of an asset or fund manager in the fund management sector. However, the underlying principles are not industry-specific and could therefore be relevant to any situation in which decision-making ability is delegated under a management contract (or similar). Other sectors in which these types of contract are commonplace include:

|

IFRS 10 also describes this concept as ‘delegated power’. This is because an agency situation arises when one or more principals delegate power to the agent. Other terminology is also used sometimes – such as ‘fiduciary control’. However, having fiduciary responsibilities to other parties is not enough to conclude that a decision-maker is an agent. IFRS 10 explains that an entity is not an agent simply because:

- others can benefit from its decisions [IFRS 10.B58]

- it is obliged by law or contract to act in others’ best interests [IFRS 10.BC130].

This guidance recognises the fact that fund managers (and similar) commonly have an ability and an incentive to act in their own interests as well in the interests of others. The terms of a fund manager’s remuneration typically include a performance-based element that aligns the fund manager’s interest with those of third party investors. Also, many fund managers hold direct interests in the underlying fund. Put another way, fund managers normally have a dual role. IFRS 10 therefore requires an assessment of a range of indicators in order to determine whether the decision-maker’s primary role is agent or principal. These indicators concern:

- scope of decision-making authority IFRS 10 Special control approach

- rights held by others (especially removal or ‘kick-out’ rights)

- remuneration IFRS 10 Special control approach

- other interests [IFRS 10.B60].

These indicators are described in more detail in the following table:

|

Indicator [IFRS 10.B62-72] |

Explanation |

|

The scope of decision-making authority IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach |

|

|

Rights held by other parties (for example, removal or ‘kick-out’ rights) |

|

|

Decision-maker’s remuneration IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach |

|

|

Exposure to variability of returns from other interests in the investee IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach |

|

In practice

An investor with delegated power is required to consider these indicators in reaching a conclusion as to whether its primary role is principal or agent. However, IFRS 10 does not specify any set levels at which one indicator, or a particular combination of indicators, leads to a definitive conclusion (except for removal rights held by a single party and exercisable without cause). Accordingly, reaching a conclusion will often involve judgment.

Despite this absence of bright lines, in our view some of these indicators will have greater practical significance than others. This is considered further below.

Scope of decision-making authority [IFRS 10.B62-B63]

IFRS 10’s various examples (see below) clarify that decision-making authority only within narrowly defined parameters is an indicator of agent status. Conversely, extensive decision-making authority is an indicator of principal status.

In our view, however, this distinction will rarely be a decisive factor in most asset or fund management situations. This is because, for investment funds, decisions about buying, selling or holding investments (ie fund or asset management) will almost always be the activity that most significantly affects future returns (ie the relevant activity).

IFRS 10 confirms that this is the case even when the fund manager is required to operate within the parameters set out in the investment mandate and in accordance with the regulatory requirements [see Illustrative Example 13 of IFRS 10].

|

Example – Different investment mandates |

|

Fund managers A and B have contracts to manage different funds (Funds A1 and B1). In both cases, remuneration is market-based and includes a stated percentage of net asset value. Each investor holds a significant direct interest in the respective fund. There are no kick-out rights. Both fund managers are required to operate within defined parameters set out in the investment mandate and in accordance with strict local laws and regulations. Fund A1 is an emerging markets equity fund and its manager has discretion to invest in a wide range of equities across different countries, sectors and companies. Fund B1 is a UK FTSE 100 tracker fund. Its manager must aim to track that index in the most efficient manner although it has some discretion in how to do so (for example, through full replication or a sampling method, and through buying underlying shares or related derivatives). Reasoning: Fund manager A has considerably more discretion than fund manager B and, all else being equal, is more likely to be a principal. However, both managers have rights to direct relevant activities and each has some discretion. Hence this might not be a strong differentiating factor. That said, in practice it will probably be unusual for a tracker fund manager to be a principal for various other reasons. For example, the remuneration for managing a tracker fund is likely to be at the low end of the scale and unlikely to include a performance-based element. |

Rights held by other parties [IFRS 10.B64-B67]

Substantive removal (or ‘kick-out’) rights held by other parties may affect the decision maker’s ability to direct the investees’s relevant activities. Indeed the only situation in which a single indicator is conclusive in isolation is that a decision-maker is an agent if a single party can remove the decision-maker without cause [IFRS 10.B65].

|

Example – Kick-out rights held by one party |

|

Investors A and B have set up a fund and hold direct investments of 40% and 60% respectively. Investor A has a fund management contract but can be removed by Investor B without cause at any time. Reasoning: Investor A’s rights to direct in the fund management contract are held as agent. There is no need for any further analysis of the other factors. Investor B therefore controls the fund. |

When kick-out rights exist that do not meet the ‘single party, without cause’ criteria (which rarely apply in practice), they need to be assessed to determine how much weight is given to them. The general guidance on substantive rights, discussed in ‘Power over the investee‘, is relevant to this. However, in our view kick-out rights are not necessarily wholly substantive or wholly non-substantive. Instead, the assessment determines how much weight is given to these rights within the overall analysis.

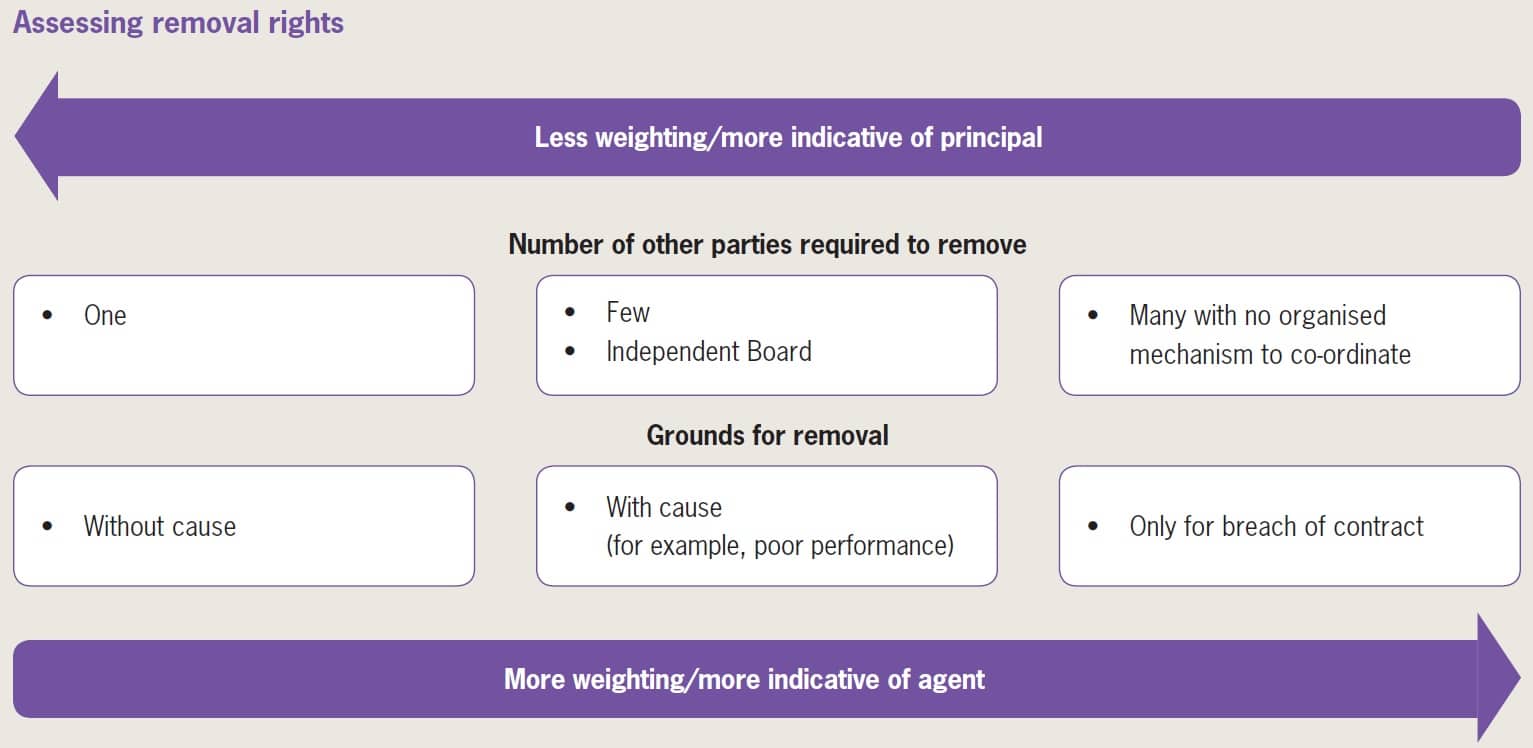

In assessing kick-out rights, the guidance in IFRS 10 suggests that two factors are particularly significant:

- the number of parties that need to act together to remove the decision-maker

- the contractual grounds on which the removal rights may be exercised (if any).

As shown below, the more parties must act together to remove a decision-maker the less substantive they are (ie less weight is given to them).

Also, a kick-out right that is exercisable without providing any reason (‘without cause’) carries more weight than one that is exercisable only in particular circumstances. A right that is exercisable only for breach of contract is protective in nature and is an indicator that the decision-maker is a principal [see Illustrative Example 14B of IFRS 10].

Kick-out rights that are exercisable by more than one party are not conclusive in isolation. The examples in IFRS 10 make it clear that:

- the absence of kick-out rights (or kick-out rights that are non-substantive) does not necessarily mean that the decision-maker is principal

- the existence of substantive kick-out rights (for example, held by a small number of investors, or exercisable by an independent Board) does not necessarily mean that the decision-maker is an agent.

The following two examples illustrate these points:

|

Example – No kick-out rights |

|

Fund manager A sets up and markets a fund to a broad range of investors. It receives market-based remuneration, including a performance element. It holds a small (<5%) direct interest. It is required to operate within a defined investment mandate and in accordance with local law and regulation. There are no kick-out rights. Reasoning: Although there are no kick-out rights it is likely that Fund manager A is agent when all the other factors are considered. |

|

Example – Kick-out rights held by a few parties |

|

Bank A sets up a fund along with three unrelated investors. Each holds a 25% direct interest. The fund management contract is awarded to Bank A’s asset management subsidiary on terms that are considered ‘at market’. The contract can be cancelled with one month’s notice (without cause) by a vote of three out of four investors. Reasoning: The kick-out rights are substantive (unless some other factor counters this – for example, if Bank A has unique skills). However, this alone is not sufficient to conclude that Bank A is agent. Nonetheless, in our view kick-out rights that can be exercised by only a few parties and without cause are a strong indicator of agent status. Accordingly, it seems unlikely that Bank A has control in these circumstances as its rights to direct relevant activities could readily be removed. |

Substantive rights held by other parties that restrict a decision-maker’s discretion are assessed in a similar way. For example, a decision-maker that is required to obtain approval for its actions from a small number of other parties is generally an agent.

Decision-maker’s remuneration [IFRS 10.B68-B70]

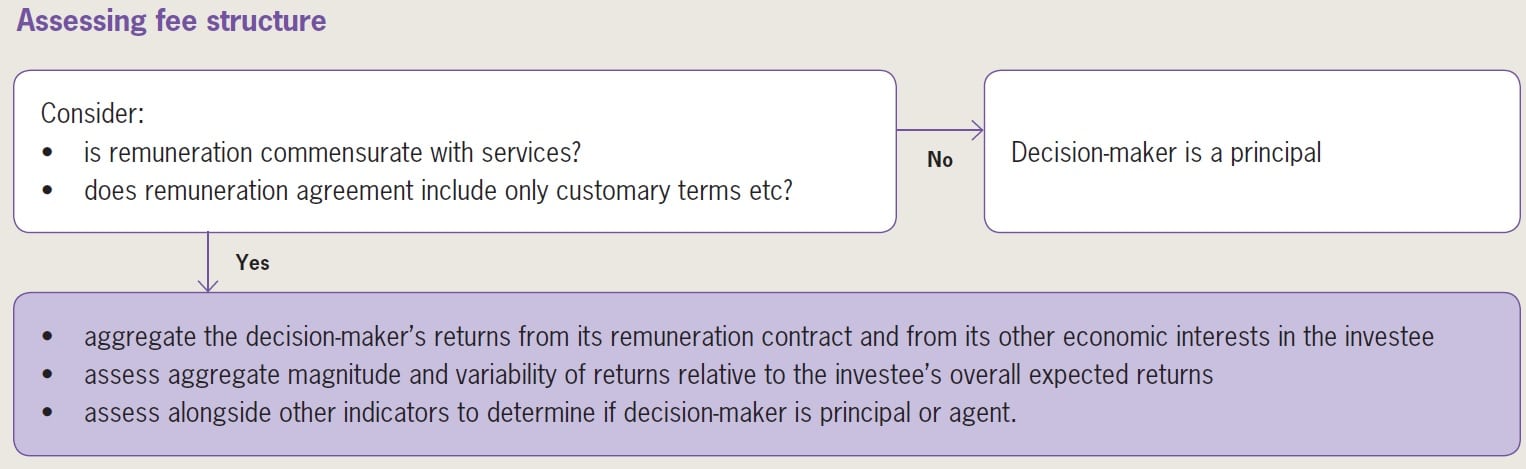

Assessing the decision-maker’s remuneration and its basis is necessary for two main reasons:

- the remuneration usually creates rights to a variable return

- as noted above, a decision-maker cannot be an agent unless remuneration:

- is commensurate with the services provided; and

- includes only terms, conditions or amounts that are customarily present in arrangements for similar services and level of skills negotiated on an arm’s length basis [IFRS 10.B69].

For retail funds, and other funds marketed to unrelated investors, a fund manager’s remuneration contract usually meets these ‘market criteria’. Indeed, the examples in IFRS 10 (while not providing guidance on assessment) include a variety of structures all of which are described as meeting the market criteria. Levels and bases of remuneration will of course vary between markets, fund size, whether the fund is marketed at retail or institutional investors, and the type of investments under management.

|

Food for thought – Remuneration structures |

|

Sectors in which the principal-agent analysis is often relevant include asset or fund management and hotel operation. In both cases the manager’s or operator’s fee structure usually creates rights to a variable return. Asset or fund management In the funds management industry an asset manager:

Hotel management Typically, a hotel operator’s fee structure includes:

|

Assuming the remuneration contract does meet the market criteria, the related rights to variable returns are assessed alongside the other three factors in reaching a conclusion. Variable returns from the remuneration contract are considered together with those from other interests in the investee in assessing the overall magnitude and variability of the decision-maker’s returns relative to the investee’s total returns.

The assessment of the decision-maker’s remuneration is summarised in the flowchart above.

In our view it is unlikely that a decision-maker would be considered a principal if the (market-based) remuneration is its only source of a variable return. This is the case even if there are no kick-out rights and the scope of decision-making authority is broad.

Exposure to variability of returns from other interests in the investee [IFRS 10.B71-B72]

In addition to its remuneration, a decision-maker may hold other interests that increase its overall rights or exposure to variable returns. IFRS 10 explains that holding other interests indicates the decision-maker may be a principal.

|

Food for thought – Other interests in the investee |

|

For the purpose of the principal agent analysis ‘other interests’ could be any type of involvement with the investee that creates rights or exposure to variable returns – see ‘Exposure, or rights, to variable returns‘. However, as a practical matter the most significant or commonplace types of interest are:

|

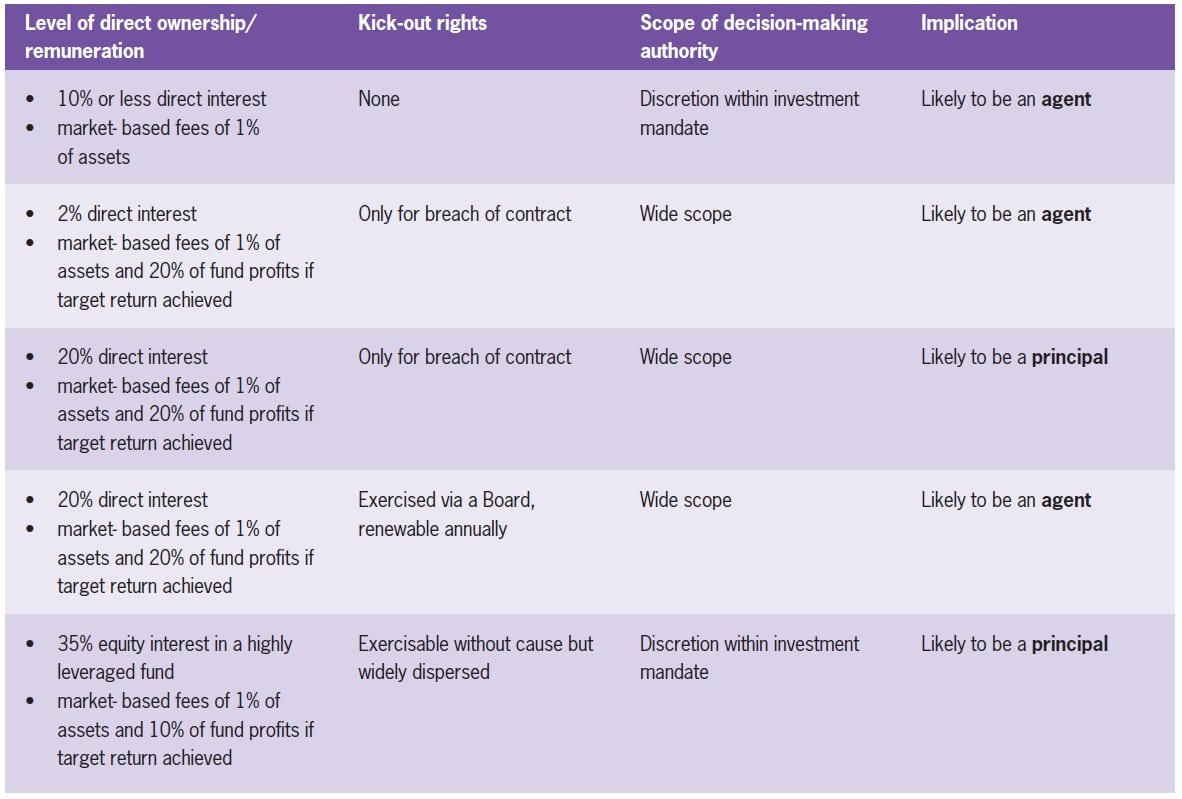

IFRS 10 requires such other interests to be assessed alongside the other indicators and does not specify any percentage ownership thresholds that are conclusive in isolation. However, the examples in the Standard at least provide some hints as to the IASB’s thinking. The examples in IFRS 10 (Illustrative Examples 13 to 15) make it clear that direct interests are an important indicator.

More specifically, these examples suggest that:

- a decision-maker is unlikely to be principal if it has no other interests beyond (market-based) remuneration

- a direct interest of 10% or less is also unlikely to result in classification as principal, even if other indicators such as a lack of substantive kick-out rights, point in that direction

- a direct interest of 20% could result in classification as either agent or principal depending on other indicators.

|

Food for thought – is there a de minimis level of direct investment? |

|

As a practical matter, some fund managers may wish to establish de minimis levels of direct investment, below which they can safely assume they are an agent without detailed analysis. Some may have used benchmarks in developing an accounting policy to apply existing requirements. Unfortunately, IFRS 10 does not specify any benchmark or de minimis threshold. To do so would also be inconsistent with the general requirement to consider all relevant facts and circumstances. That said, the examples in IFRS 10 suggest that a manager with a market-based remuneration agreement and a direct holding of 10% or less is unlikely to be a principal. |

Applying the indicators together

IFRS 10 includes a number of examples to illustrate the application of the four indicators in combination [Illustrative Examples 13 to 16 of IFRS 10]. Some of the inferences that might be drawn from these examples have been discussed already here.

The key aspects of Illustrative Examples 13 to 16 are summarised in the table below (although reference should be made to the full text of the examples in IFRS 10 for a complete explanation of the fact patterns and indicative conclusions):

Franchises

In a franchise operation, both the franchisor and franchisee normally have some decision-making rights and some rights to variable returns from the franchise business. A question therefore arises as to whether the franchisee or franchisor has control (or whether control is shared).

|

Food for thought – Franchises |

|

In a franchise operation one party (the franchisee) pays another (the franchisor) for rights to operate a business using an established trade name and business model. The franchisee pays for rights to use the trade name and know-how for a period of time, and normally receives other services such as training and advertising. The franchisee typically pays the franchisor:

IFRS 10 also notes that a franchise agreement often gives the franchisor rights that are designed to protect the franchise brand and some decision-making rights with respect to the operations of the franchisee [IFRS 10.B29]. For example, the franchisee is commonly obliged to follow the franchisor’s requirements on matters such as staff uniforms and brand imagery and sometimes on pricing and sourcing of equipment and supplies. |

A large part of the assessment in practice relates to whether the franchisor’s rights are protective or go beyond that.

IFRS 10 provides some guidance on this assessment [IFRS 10.B30-B33]. The guidance emphasises that the franchisor’s rights are often protective and do not then prevent the franchisee from having control.

Key points are that:

- a franchisor’s rights that are designed to protect its brand are protective in nature and do not generally prevent others from having control

- other decision-making rights of the franchisor also do not necessarily prevent others from having control

- the lower the level of financial support provided by the franchisor and the lower the franchisor’s exposure to variability of returns from the franchisee the more likely it is that the franchisor has only protective rights

- by entering into the franchise agreement the franchisee has made a unilateral decision to operate its business in accordance with the terms of the franchise agreement, but for its own account.

Franchises do of course vary extensively and each needs to be assessed based on its specific facts and circumstances. Given that both parties have some decision-making the assessment of relevant activities is critical.

|

Example – Franchise |

|

Franchisor A owns the trade name and business model-related IP for a fast food business. Franchisee B enters into an agreement giving it exclusive rights to operate the franchise business in a specified location for 5 years, renewable at B’s option. Franchisee B pays an initial franchise fee, continuing royalties of 5% of revenues, and fees for advertising and other services. Franchisee B is entitled to all residual profits after paying these fees. Under the terms of the agreement:

Reasoning: Both Franchisor A and Franchisee B have rights to variable returns and have decision-making rights over some activities. Franchisor A’s decision-making rights may extend beyond simple brand protection (because, for example, they include rights over input and output prices). An assessment is therefore needed as to which activities have the greatest effect on returns. If it is determined that the most relevant activities are staffing, financing the franchise and renewal then Franchisee B would have control of the business. |

Annualreporting provides financial reporting narratives using IFRS keywords and terminology for free to students and others interested in financial reporting. The information provided on this website is for general information and educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice. Use at your own risk. Annualreporting is an independent website and it is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or in any other way associated with the IFRS Foundation. For official information concerning IFRS Standards, visit IFRS.org or the local representative in your jurisdiction.

IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach

IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach

IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach IFRS 10 Special control approach