Share options give the holder the right to buy the underlying shares at a set price, called the ‘exercise price’, over or at the end of an agreed period. If the share price exceeds the option’s exercise price when the option is exercised, then the holder of the option profits by the amount of the excess of the share price over the exercise price. Benefit is derived from the right under the option to buy a share for less than its value.

The holder’s cost is the exercise price, whereas the value is the share price. It is not necessary for the holder to sell the share for this profit to exist. Sale only results in realisation of the profit. Because an option holder’s profit increases as the underlying share price increases, share options are used to incentivise employees to contribute to an increase in the price of the underlying shares.

Employee options are typically call options, which give holders the right but not the obligation to buy shares. However, other types of options are also traded in markets. For example, put options give holders the right to sell the underlying shares at an agreed price for a set period.

Given that holders of put options profit when share prices fall below the exercise price, such options are not viewed as aligning the interests of employees and shareholders. All references in this section to ‘share options’ are to employee call options.

Share options granted by entities often cannot be valued with reference to market prices. Many entities, even those whose shares are quoted publicly, do not have options traded on their shares. Options that trade on recognised exchanges such as the Chicago Board Options Exchange are created by market participants and are not issued by entities directly.

Even when there are exchange-traded options on an entity’s shares for which prices are available, the terms and conditions of these options are generally different from the terms and conditions of options issued by entities in share-based payments and, as a result, the prices of such traded options cannot be used directly to value share options issued in a share-based payment.

For example, the contractual lives of traded options are generally significantly shorter than the expected terms of share-based payments. In the absence of market prices, valuation techniques are used to value share options. (IFRS 2.B4)

The value of a share option at exercise is relatively straightforward. If the exercise price is below the share price, then the value of the option is equal to the share price less the exercise price. However, if the exercise price is above the market price, then the option has no value. In these circumstances, an employee wishing to buy shares would be expected to buy shares in the open market rather than exercising the option.

Exercising the option would cause a loss because the holder would be acquiring an item for more than its market price. The ability of an option holder to avoid a loss by not exercising the option (i.e. the option expires unexercised) highlights a feature of options – i.e. the option holder has the right but not the obligation to buy the shares. Therefore, the value of an option at exercise is the greater of zero or the share price less the exercise price.

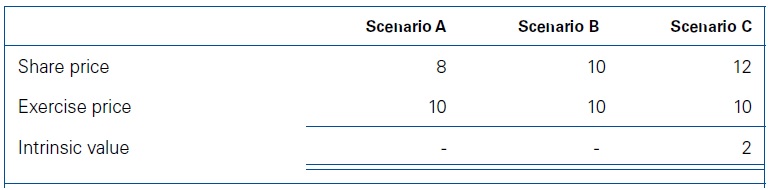

The following table illustrates the value of an option at expiry under various share price scenarios.

|

Assume that an employee holds an option to buy shares in Company C at 10. At expiry, this right will have value if it allows the employee to buy shares at a price below that prevailing in the market.

Notes

|

The ‘pay-off’ of an option is the value of the option for a given underlying share price. A ‘pay-off function’ describes the formula to calculate the pay-off. For example, on a plain vanilla – i.e. standard – call option, the pay-off formula is the greater of the share price less the exercise price or zero.

More complex pay-off functions can be created. For example, when an entity wishes to place a cap on the maximum that an employee could earn from an award, the pay-off formula would be the greater of the share price less the exercise price, up to a maximum amount of the cap, or zero.

The pay-off or value of an option at exercise is relatively straightforward because the share price is known. However, before exercise the future share price at the exercise date is not known, which makes the valuation of an option more complex. Option valuation models use mathematical techniques to identify a range of possible future share prices at the exercise date.

From these possible future share prices, the option’s pay-off can be calculated. The fair value of an option at its grant date is estimated by calculating the present value of the possible future intrinsic values, which are estimated using a probability-weighted outcome technique (hereafter referred to as ‘probability-weighted values’).

Fair value ESOPs – An option has two primary components of value: intrinsic value and time value. Time value is the difference between the total value of an option and its intrinsic value and can be viewed as having two components: minimum value and volatility value.

As stated previously, intrinsic value can be calculated easily on any given date, but option pricing models are needed to estimate the overall value of an option, including its time value. These terms are described further as follows.

- Intrinsic value: Intrinsic value is the greater of (a) the share price minus the exercise price and (b) zero. Intrinsic value is the pay-off that would be realised by the option holder, assuming that they exercised the option on the measurement date, even though, in practice, the option may not be exercisable – e.g. because it has not vested.

- Minimum value: Minimum value is equal to the value of the underlying share, less the value of any dividends to which the option holder is not entitled, less the present value of the exercise price; it represents the value to the option holder of delaying payment of the exercise price until the exercise date. Under standard present value techniques, future cash flows – in this case, cash outflows related to payment of the exercise price – have a present value below the nominal future amount.

- Volatility value: Volatility value relates to the upside potential associated with an option.

Fair value ESOPs – Option pricing models use six key assumptions, as discussed below.

Fair value ESOPs – Assumptions

There are a number of assumptions or inputs that are used in option pricing models. These assumptions and their relationship to an option’s value are as follows and are discussed next in more detail. (IFRS 2.B6)

|

The higher the share price |

The higher is the value of the option |

|

The higher the exercise price |

The lower is the value of the option |

|

The higher the expected volatility |

The higher is the value of the option |

|

The higher the expected dividends not receivable |

The lower is the value of the option |

|

The higher the risk-free rate |

The higher is the value of the option |

|

The higher the expected term |

In general. the higher is the value of the option |

The expected term of an option is the length of the period over which the option is expected to be unexercised. Expected term is the contractual life of an option adjusted to reflect early exercise of the option by employees – i.e. employees exercising an option before the end of its contractual term. In general, the longer an option’s expected term, the higher is the value of the option.

However, there are circumstances in which it will be optimal for an option holder to exercise an option earlier – e.g. because there are large dividends being paid on the underlying shares, so that a shorter term is better. Expected term is discussed in detail below.

Each of these assumptions is discussed in detail below. In our experience, expected volatility and expected term are often the assumptions with the greatest potential subjectivity.

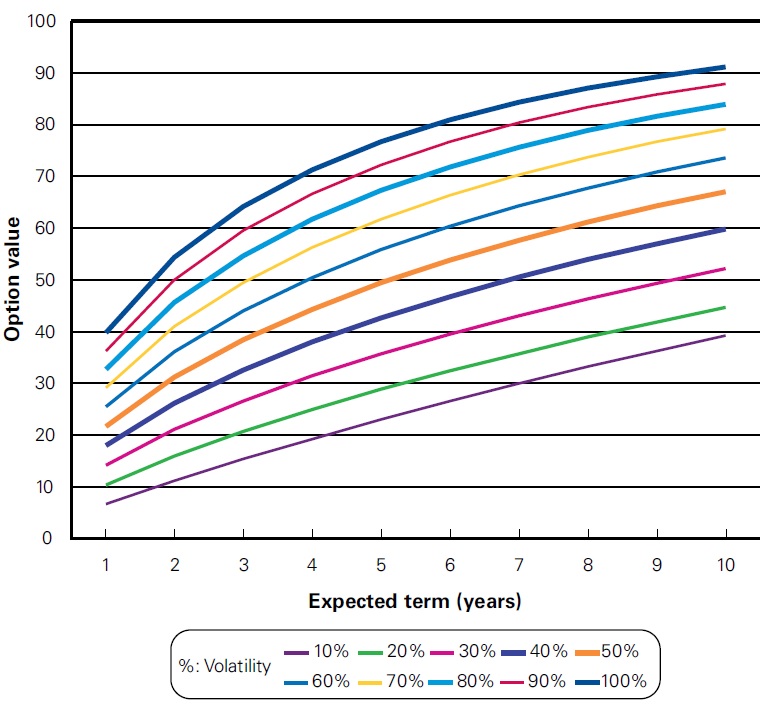

The table below shows the different option values that result from changing an option’s expected term and expected volatility assumptions, assuming a share price and exercise price of 100, a risk-free rate of 5 percent and a dividend yield of 0 percent.

Fair value ESOPs – Expected volatility expected term

A graph of this table shows that option values are not a linear function of expected term. This means that the value of an option with a two-year term is not twice the value of an option with a one-year term.

As a result, calculating an option’s value based on the average date at which all employees are expected to exercise their options may be less accurate than stratifying employees into different groups based on similarity of early exercise behaviour and separately valuing the options received by each such group. (IFRS 2.B20) This is discussed further below.

Effect on option value of varying the expected term for a specified volatility

Selecting inputs to option pricing models

The valuation of an option should use the expectations for inputs that would be reflected in a market price on the measurement date. In estimating such inputs, a range of factors including the historical values of the individual parameters would be considered.

When there is a range of reasonable expectations, an expected value is calculated by weighting each specific expectation with its associated probability.

In some circumstances, specific factors may indicate that the historical outcome may be a poor predictor of future experience.

For example, in estimating the expected dividend input to an option pricing model, historical dividend levels would not be used without considering possible changes to dividend policy, future capital requirements, dividend forecasts from market analysts etc. (IFRS 2.B11-B14)

For an entity with publicly traded shares, the share price used to value an option at grant date is generally the closing share price on grant date. Daily prices can be sourced from data services, stock exchange pricing data etc. For an entity whose shares are not traded publicly, valuation techniques are used to estimate the fair value of shares.

The higher the share price, assuming that all other inputs remain the same, the greater is the value of an option. For a given exercise (or cost) price, a rational holder would prefer a higher underlying share price to a lower underlying share price.

An option with a zero intrinsic value has a total value that is greater than zero before expiry of the option because the share price might move in-the-money before expiry. Clearly, the share price input also affects the value of an out-of-the-money option.

For example, for an option with an exercise price of 20, the value of the option is higher when the underlying share is trading at 15 than when the underlying share price is 10. This is because, although in either case the option has zero intrinsic value, the likelihood of the option expiring in-the-money is higher in the former case.

Exercise price

The exercise price of an option, which is also referred to as the option’s ‘strike price’, is the price at which the option holder is entitled to acquire the underlying share.

Frequently, an option plan states that options should not be issued with an exercise price below the share price on grant date. This may lead a valuer to use an exercise price equal to the share price in the option valuation model, which may not always be appropriate.

In particular, the exercise price is a matter of contract and will be set out in the agreement with the recipient and may differ from the share price on grant date.

For example, the exercise price may be set before grant date – i.e. before the share price is measured, because of delays in communicating details of the option grant to employees (see Determination of grant date in Employee equity settled share-based payments).

Because the exercise price represents the cost of the share to the holder, they will prefer a lower exercise price, assuming that all other inputs remain the same. Similarly, an option holder is worse off if an award’s exercise price is higher.

Some entities issue options with a zero exercise price. This is equivalent to issuing unvested shares when the holder does not have a right to a dividend during the vesting period. Such an award can be modelled in an option pricing model, though a very small but greater than zero exercise price input is used (In the BSB model, the formula includes the exercise price in a denominator. Attempting to divide by zero would cause the model to report an error).

If an option holder is entitled to dividends during the vesting period, then an option with a zero strike price will have a value indistinguishable from the share price, assuming that all other inputs remain the same.

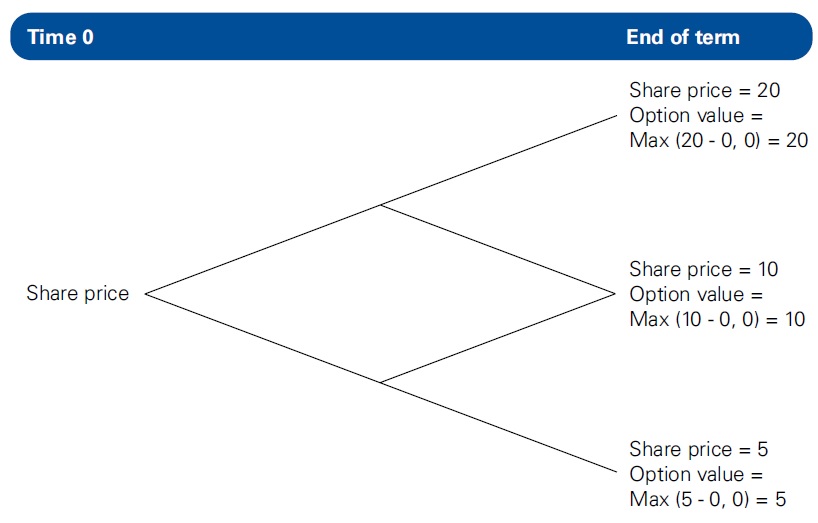

The reason why an option with a zero exercise price is considered equivalent to an unvested share can be understood by considering the option’s intrinsic value. Consider first an option on a non-dividend-paying share. The value of the share is the present value of the probability-weighted possible future share prices.

The value of an option is the present value of the probability-weighted possible future intrinsic values. If an option has a zero strike price, then the possible future share prices and intrinsic values are equal so the value of the option must equal the value of the share, as illustrated below.

The diagram shows a share price lattice, which includes different possible future share prices, over time, moving from left to right (from the valuation date). This illustrates that the future possible share prices are equal to the future intrinsic values. A small number of possible future share prices is shown for simplicity but the principle is unchanged if the number of share prices is increased.

For a share that entitles the holder to dividends, an option with a zero strike price is not equal to the full current value of a share. In essence, the current value of a share is based on its expected future cash flows – i.e. dividends – to shareholders.

The value expected to be realised by an individual shareholder will comprise expected dividends and expected future proceeds from sale of the shares.

However, future sale proceeds should be based on the future dividends thereafter. In this way, the value of a share over its life is ultimately related to expected dividends.

Because option holders are not generally entitled to dividends paid during the vesting period, the value received by the option holder is worth less than the value of shares on which dividends are expected during the vesting period. Such an instrument can be valued using an option pricing model with a very small, but greater than zero, exercise price.

Expected volatility

The expected volatility of returns on the underlying share is a key assumption when valuing an option. Volatility is a measure of the range of possible future returns on a given investment. Zero volatility means that the actual return on an investment is always equal to its expected return and only applies to risk-free investments. Volatility other than zero reflects the fact that for investments with some risk of variability, actual returns will often differ from expected returns.

Higher volatility means that the range of possible share price returns is wider and that differences between actual and expected returns are likely to be greater than when there is lower volatility.

Option pricing models use the annualised standard deviation of the continuously compounded rates of return on a share over time as the measure of volatility. (IFRS 2.B22-B23)

The rate of return on a share comprises both share price movements – i.e. capital gains or losses, whether realised or unrealised over a period – and dividends, if applicable. Volatility of 30 percent, for example, as an expression, means one standard deviation of returns is the range of ereturn+/-0.30, in which (e) is the base of natural logarithms and is used due to the greater ease of working with natural logarithms in complex formulae. Option pricing models use the risk-free rate as the return assumption.

The expected volatility of a share provides a range within which the actual return is expected to fall two-thirds of the time. For example, if a share has an expected return of 10 percent and expected volatility is 40 percent, then annual share returns are expected to fall within a range of -30 percent to +50 percent two-thirds of the time (10% – 40% and 10% + 40%, respectively). If the share traded currently at 20, then the share price in a year would be expected to be in the range of 14.82 (20 x e-0.30) to 32.97 (20 x e0.50), two-thirds of the time. (IFRS 2.B24)

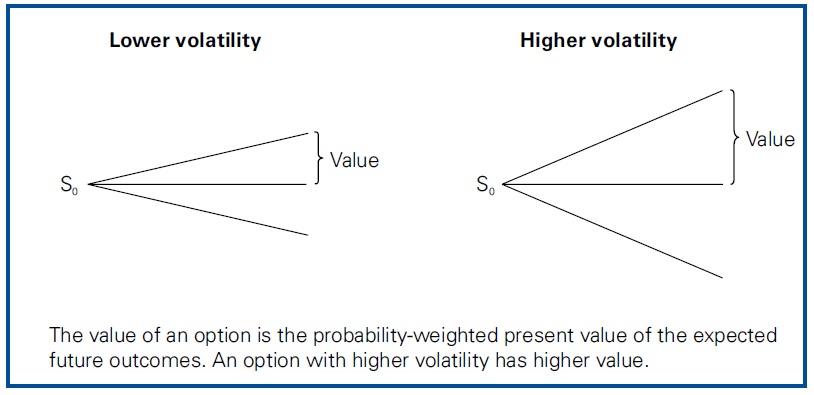

One might expect that the greater the possible dispersion of returns – i.e. the wider the range of possible returns – and the higher the uncertainty about the ultimate outcome, the lower the value of an investment would be. However, this is not the case in the context of option valuation. For shares, greater possible upside is balanced by greater possible downside and greater risk will often result in a lower value for a share.

However, for options, the downside is a zero value and the amount by which the share price is below an option’s exercise price is irrelevant. For example, whether an option is out-of-the-money by 1 or 100 at expiration, the intrinsic value is zero.

Therefore, in the case of a risky share, there may be a greater likelihood that the share price will end up significantly below the exercise price compared with a less risky share. However, the pay-off to the option holder in either scenario is the same – i.e. zero. The greater upside benefits available for a high-volatility share with similar downside risk means that higher volatility leads to a higher value for an option on that share.

Unlike the share price and exercise price assumptions, expected volatility cannot generally be taken from a single objective source and there is subjectivity in estimating this model input.

Some factors to be considered in estimating expected volatility include the following. (IFRS 2.B25)

- The implied volatility (see below) of traded share options on the entity’s shares or traded instruments that have option features such as convertible debt.

- The historical volatility (see below) over the most recent period commensurate with the expected term of the instrument. For example, in estimating the expected volatility of an option with a five-year expected term, significant weight would generally be placed on the historical volatility of the shares over a five-year period ending on grant date.

- The length of time that the entity’s shares have been traded publicly (public company). For example, an option may have an expected term of seven years but the entity’s shares may have been traded publicly for only six months. As such, the entity has limited experience with the historical volatility of its own shares on which to base longer-term volatility estimates.

- The tendency of volatility to return to longer-term average levels, which is sometimes referred to as ‘reverting to its long-term mean’ or to be ‘mean-reverting’. For example, a period of very high volatility may relate to an event that is not expected to recur. In such circumstances, it could be appropriate to exclude the volatility from such a period. However, the basis for the exclusion of specific historical periods should be carefully supported, as discussed below. For example, an entity that disposed of its core business (e.g. high-risk development of a new pharmaceutical) and used the funds to enter a different, less volatile business (e.g. a product with an existing stable revenue stream) may be able to support the exclusion of a historical period.

- Appropriate and regular intervals for price observations. (IFRS 2.B25)

Unlisted entities do not have quoted share prices and look to the historical and implied volatilities of comparable listed entities. (IFRS 2.B29 )

There are a number of issues that arise in practice when estimating expected volatility, including the following.

- The period over which share price volatility is estimated.

- Possible adjustments to remove especially volatile periods from the historical period over which volatility is calculated.

- Sourcing volatility information, especially implied volatility data.

- The trading volume required to place (exclusive) reliance on implied volatility.

- The weightings applied to implied and historical volatility estimates.

Two measures of volatility are historical volatility and implied volatility.

Historical volatility

Historical volatility is a measure of the volatility of share returns over a given interval (e.g. daily, weekly, monthly), over a specified term (e.g. one year, two years, three years etc), which can be measured over time. For example, for an award with a five-year expected term, one might focus in particular on the volatility of daily share returns over the five-year period preceding the valuation date.

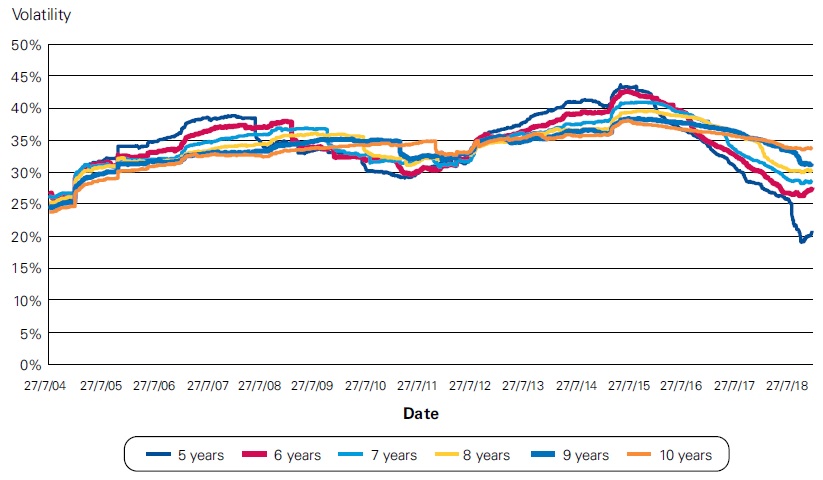

This might be calculated only for the most recent five-year period on the valuation date. Alternatively, one might measure a series of rolling five-year daily (or other period) volatilities, starting on grant date and moving back over time, one day at a time, to have more information on movements in historical volatility over time to understand trends and outliers. This is shown in a graph below.

Share price volatility

Historical volatility estimates may be provided by information sources or may be calculated from a sample of share prices. Whether they are sourced externally or calculated directly, a consistent method is applied to calculate historical volatility.

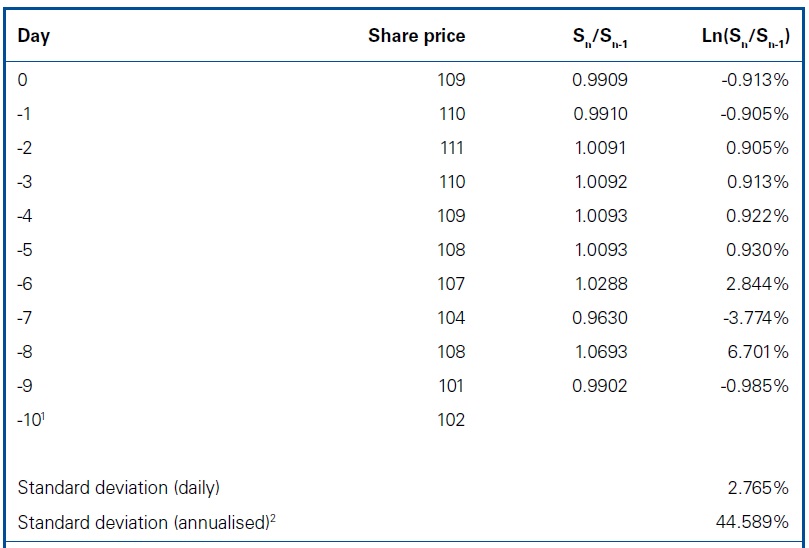

To illustrate this, the steps involved in calculating historical volatility from a sample of share prices are as follows.

- Source share prices for the interval selected – e.g. daily share prices over the past 10 years. The share prices of dividend-paying shares should be adjusted to remove the effect of the payment of dividends, which cause a reduction in the price of a share unrelated to generalised volatility. Such adjustments are often made by the data provider but may also be made directly.

- Calculate the share price returns on a natural logarithm basis. This is done by dividing each share price by the preceding price and then obtaining the natural logarithm. This can be done using a spreadsheet function. Option pricing models use continuous compounding for which natural logarithm returns are required. It is beyond the scope of this discussion to explain the specific detailed basis for why logarithms are used to perform these calculations.

- Calculate the standard deviation of the returns. Most spreadsheet programs include a function to perform this calculation.

- Convert the resulting standard deviation into an annualised standard deviation. This is done by multiplying the standard deviation by the square root of the number of the intervals selected in a year. For example, if daily share price volatility was calculated, then annualised share price volatility is calculated by multiplying the daily estimate by the square root of 260 (there are approximately 260 trading days in a year). If weekly share price volatility was calculated, then annualised share price volatility is calculated by multiplying the weekly estimate by the square root of 52.

The steps are illustrated as follows, when day zero may be either grant date or the previous day.

Notes

1. Eleven days is too short a period from which to sample share returns but is used for simplicity above.

2. To convert from a daily volatility estimate to an annual volatility estimate, use the square root of time – i.e. multiply the daily standard deviation by a factor of 260^0.5 (there are approximately 260 trading days in a year).

S: Share price.

The following are some of the factors that are considered in using historical volatility.

- Older historical periods may be less relevant than more recent periods. For example, a company may have changed its operations, disposed of a core business, significantly changed its capital structure etc. (Capital structure influences the volatility of an entity’s shares. When an entity is leveraged, one effect of the debt is to amplify the volatility of the share price. Share price volatility primarily arises from changes in the value of an entity’s operations. Debt in the capital structure will have volatility below the volatility of the value of the operations, and equity will have volatility above the volatility of the value of operations. The greater the proportion of debt in the capital structure, the greater is this effect.)

- A specific historical period may be excluded from the volatility measurement period if during that period the share price was extraordinarily volatile and such extraordinary volatility is not expected to recur. In many cases, events or other factors that caused spikes in volatility may be reasonably expected to recur, in which case specific historical periods would not be excluded. It is important to remember that, because the expected term of many options is relatively long, a relatively short period of volatility will be a relatively small part of the overall measurement period. (IFRS 2.B25(d) )

- A newly publicly traded entity may not be able to calculate historical volatility over a period that is commensurate with the expected term of its options. Such an entity should calculate its own historical volatility for the longest period available. It should also consider the historical volatility of comparable entities over a period that is commensurate with the expected term. If the volatility of comparable entities is used to estimate the volatility of an entity – e.g. for privately held or newly publicly traded entities – then differences in capital structure and operations should be considered. Adjusting for any such differences is a matter of judgement rather than being subject to a formulaic adjustment mechanism. (IFRS 2.B26)

Implied volatility

Implied volatility is a measure of the volatility assumption implicit in a traded instrument. For example, for an option that is traded on an options exchange, the price of the option as well as variables such as the underlying share price, the exercise price, the contractual term and the risk-free rate over the term are known.

With these variables being known, it is possible to calculate the expected volatility implicit in the traded option price. This is because the implied volatility variable, used together with the other model inputs in a standard option valuation model such as BSM, results in a model value that is equal to the option’s price. This implied volatility is often regarded as the market’s estimate of volatility over the term of the quoted instrument.

Given that implied volatility is often regarded as the market’s estimate of expected volatility over the term of an instrument, it might be expected that it would always be used in share option valuation. Implied volatility already reflects historical volatility to the extent to which the market believes that historical volatility is relevant over the expected term of an instrument. However, it is frequently not possible to apply implied volatility for a number of reasons, including the following.

- The entity does not have traded options or other derivative securities on its shares. IFRS 2.B25(a) states that an entity may be able to calculate the implied volatility of traded instruments with option features such as convertible debt. This may be difficult to apply in practice because such instruments often have a number of features that complicate the estimation of implied volatility. For example, convertible debt may have callable or puttable features that complicate the derivation of implied volatility estimates related to its conversion features.

- Traded options generally have significantly shorter maturities than the expected term of options granted to employees. For example, many traded options have lives of three, six or nine months, whereas the contractual terms of an employee option can be 10 years.

- Quoted options may not be traded sufficiently actively to be a reliable basis for estimating expected future volatility. Market data is frequently used, if it is available, on the basis that the interaction of multiple buyers and sellers in a market brings a balanced perspective from sources highly incentivised to make correct estimates. However, when a market is not active such ‘wisdom of crowds’ is not present and the resulting values are less reliable. It is worth noting that there may be a number of options traded on the entity’s shares with different terms – e.g. puts vs calls, different maturity dates, different exercise prices etc. The large number of options available means that trading volumes may be split. Traded option information is useful in such circumstances, but lower volumes may reduce the level of reliance that can be placed on the data.

- The traded instrument from which the implied volatility estimate is derived may have an exercise price that is either heavily in or out-of-the-money. Implied volatility derived from such instruments is regarded as less reliable when valuing an at-the-money option.

- A study of implied and historical volatility data provides information to help estimate expected volatility. However, in the absence of implied volatility from an actively traded instrument with a remaining life equal to the expected term of a share option, an entity will have to weigh the merits of different historical and implied volatility data points in estimating expected volatility. An entity may conclude that it is appropriate to weight both implied and historical volatility. The weights attached to the implied and historical volatility estimates are a matter of judgement. No strict formula or rules of thumb exist to calculate such weights.

Expected dividends

The treatment of expected dividends in a valuation of unvested shares or options depends on whether the holder is entitled to dividends or dividend equivalents during the vesting period. An example of a dividend equivalent is a reduction of an option’s exercise price by the amount of a dividend.

This section will first discuss the valuation of unvested shares and options when the holder is not entitled to dividends or dividend equivalents, before discussing circumstances in which holders are entitled to dividends or dividend equivalents. (IFRS 2.B31-B32)

Dividends paid by an entity reduce the value of an option on the entity’s shares, if all other inputs remain the same. Payment of a dividend does not change a shareholder’s wealth. Instead, payment of a dividend monetises a portion of a share’s value so that after payment of a dividend, a shareholder holds cash plus a share whose value is equal to the pre-dividend value of the share less the amount of the dividend.

For example, assume that a share is trading at 10 and then pays a dividend of 1. The price of the share will decrease by the amount of the dividend to 9. Before payment of the dividend, the shareholder held a share worth 10; after payment of the dividend, they hold a share worth 9 and cash worth 1, with no change in their aggregate wealth.

However, an option holder is worse off by payment of a dividend. Until they exercise their options and hold the underlying shares, they are not generally entitled to dividends. Therefore, option holders receive all of their return from share price appreciation and anything that reduces the underlying share price, such as a dividend payment, will reduce the value of their options.

Continuing the example, suppose that an option holder held an option on the underlying share that had an exercise price of 9.5. Before payment of the dividend, the option was in-the-money and had an intrinsic value of 0.5. However, after payment of the dividend and the resulting decline in the share price, the option moves out-of-the-money. This illustrates that the higher the dividend is on an underlying share, the lower is an option’s value.

Dividends can be incorporated into an option pricing model using the estimated dividend amounts, though it is more common to use an estimated dividend yield. Dividend amounts, if they are used, should be discounted at the risk-free rate from the expected dividend payment date to the measurement date. If dividend payments are modelled as specific amounts, then increases in the dividend over the expected term should be considered. (IFRS 2.B35)

Option models frequently incorporate the effect of dividends by reducing the current price of the share from which a future distribution of share prices is calculated. This is usually accomplished in the model through the entry of the dividend assumption.

In estimating expected dividends over the expected term, one should consider the following.

- Historical dividends or dividend yield. However, reported historical dividend yield may be unreliable as an estimate of expected dividend yield. For example, if a dividend is perceived to be unsustainable, then investors will mark down the price of a share (the denominator in the dividend yield calculation) before the decline shows up in the actual dividends paid (the numerator in the calculation). This can be apparent when the dividend yield appears very large relative to an entity’s historical practices and/or its cost of capital. For example, for many banks during the financial crisis, the reported dividend yields were very large because the market anticipated a decline in dividends before the dividend was cut.

- Planned changes to the dividend over the expected term. An entity may not have paid dividends historically but is expected to pay dividends within the expected term of a share-based payment award. In these circumstances, the expected dividends should be considered in the option valuation. An entity that does not pay dividends and has no plans to do so would use a dividend yield assumption of zero.

- Guidance on dividends provided by management to the market.

- Forecast dividends: e.g. from investment analysts and analyst reports.

- Sustainability of dividends given current and projected profitability and current and projected investment requirements.

- Changes in the nature of the business, including its cash generation and cash requirements.

A valuation should consider whether the terms of an option include any dividend protection features so that the holder is entitled to dividends or dividend equivalents during the vesting period. Such terms protect an option holder from a decline in the value of the option that would otherwise occur from the payment of a dividend.

Such a feature can take the form of a reduction in the exercise price by the amount of any dividends paid. When an option includes a dividend protection feature, the dividend assumption in the model is generally set at zero because the dividend protection feature prevents any decline in the value of the option caused by the payment of a dividend. (IFRS 2.B32-B34)

Risk-free rate

The risk-free rate used in an option pricing model is generally derived from zero coupon government bond yields in the currency in which the option’s exercise price is denominated with a maturity equal to the expected term of the award. (IFRS 2.B37)

It is possible to incorporate the term structure of interest rates into certain option pricing models. However, this is not possible for closed form models and dramatically increases the complexity of lattice models. A term structure is rarely used in practice.

Issues arise when there are no appropriate government bond rates or when government bond rates do not represent risk-free rates, particularly when the credit risk of certain governments has increased.

One indication of whether and the extent to which credit risk is included in a government bond rate may be pricing in derivative markets – e.g. credit default swaps on debt issued by the government concerned. In these circumstances, appropriate substitutes for the risk-free rate should be found.

This could include the use of government bond rates from a more creditworthy country that uses the same currency – e.g. for countries using the euro, the rate used would be from the country with the highest credit rating in the euro zone. (IFRS 2.B37)

Other approaches might include adjusting available government bond rates from countries that are believed to be risk-free for expected inflation differentials between that country and the country in whose currency the exercise price is stated.

The higher the risk-free rate, the greater the value of an option. The risk-free rate is sometimes referred to as the ‘assumed drift of the share price’ – i.e. the share price is assumed to increase on average at the risk-free rate (less the dividend yield) and therefore the higher the risk-free rate, the greater the average assumed increase in price. Use of the risk-free rate is consistent with risk-neutral pricing, an assumption of option pricing models.

Use of the risk-free rate is not intended to suggest that options or the underlying shares are risk-free. However, the riskiness of the share is already reflected in the share price input assumption into the option valuation model. Moreover, option pricing models assume that an investor could create a portfolio that hedges the risk from an option.

Government bond rates can be sourced from a number of data sources.

Expected term

Options may be exercisable at the end of their contractual life, at any point up to the end of their contractual life or at certain periods over the contractual life. An option that is exercisable only at the end of its contractual life is referred to as a ‘European option’.

An option that is exercisable at any point over its life is referred to as an ‘American option’. An option that is exercisable at specified periods over its life is referred to as a ‘Bermudan option’ (on the basis that Bermuda lies between America and Europe).

An employee option is generally a Bermudan option, because it is usually exercisable at any point until the end of its life once the vesting period has passed, subject to potential ‘blackout periods’ when employees are restricted from trading in their employers’ shares.

In general, it is sub-optimal to exercise an option before the end of its contractual life. This is because when an option is exercised, its intrinsic value is secured but the time value of the option is lost. As a result, in most cases, models suggest that options should be held through to the end of their contractual life.

An exception to this general principle arises for options on dividend-paying shares. Payment of a dividend will tend to accelerate option exercise so that the option holder can benefit from payment of the dividend.

However, in our experience it is observed that employees exercise their options early. This may, in part, be because employee options are not tradable, and therefore any employee wanting liquidity cannot sell their options and has to exercise the options and sell the underlying shares. Similarly, holders who cease employment with the entity are generally required to exercise their options within a short period.

The inability to transfer an option is reflected through an adjustment to the expected term to reflect early exercise rather than through the application of a separate discount for lack of marketability. (A discount for lack of marketability may be appropriate for the share price input if there are post-vesting restrictions on the transferability of the underlying shares that are obtained when an option is exercised)

As a result, IFRS 2 provides that options are valued based on their expected term rather than their contractual life. Expected term reflects option holders’ early exercise decisions. (IFRS 2.B16)

Traditionally, expected term has primarily been incorporated into the value of an employee option by using a term assumption in the option pricing model that is shorter than the contractual life. However, entities have also sought to identify direct drivers of early exercise behaviour and incorporate these in their option pricing model when the contractual life is used.

For example, lattice models have been used when early exercise has been assumed based on the ratio of the share price to the exercise price.

If an entity does not have experience of employees exercising options, then there is no entity-specific information on which early exercise assumptions can be based. For example, employees in a private entity will often not exercise their options because if they were to do so they would be left holding risky, illiquid shares. As a result, decisions made by employees when an entity was private may not be relevant after such an entity has gone public.

In general, an entity should base its estimate of the expected term on its own specific history. Industry data may become available over time but may not be appropriate for a specific entity’s facts and circumstances – e.g. because of differences in size, share price volatility, employee wealth, rank or age, underlying share price performance etc.

If entity-specific information does not exist, then an entity forms an estimate.

The earliest date at which an option could be exercised is the end of the vesting period, whereas the last date is the end of the contractual life. In the absence of entity-specific information, entities have used the average of these two periods, which is calculated as (vesting period + total contractual life) / 2.

For example, if an option had a 10-year contractual life and four-year cliff vesting (see A2.70), then the expected term under this approach would be seven years ((4 + 10) / 2). When this approach is used because an entity has limited employee exercise history, the entity collects and analyses employee exercise behaviour in order to use entity-specific information when sufficient exercise history is available.

A share-based payment award with a longer vesting period will generally have a longer expected term than a share-based payment award with a shorter vesting period, even if they both have the same contractual life. Share-based payment awards with a longer vesting period may have a higher calculated value through a longer expected term.

This is somewhat counterintuitive because it might be expected that an option with a shorter vesting period would be more valuable than an option with a longer vesting period because the holder in the former case has greater discretion, flexibility and control over when they decide to exercise the option.

However, because options should not generally be exercised early, features that tend to extend the life of an option, including a longer vesting period, will result in a higher value in an option valuation model compared with features that shorten the life of the option.

Other factors to consider in estimating expected term include the following. (IFRS 2.B18-B19)

- Whether one should apply different expected term assumptions for different groups of employees. For example, senior executives may be expected to hold options for longer periods than other employees, partly because senior executives may be expected to hold shares to demonstrate confidence to shareholders and also because senior executives frequently have other sources of wealth beyond options that can be used to fund cash requirements. Because options are not a linear function of expected term (e.g. the value of an option with a two-year term is not twice the value of an option with a one-year term), averaging expected term assumptions across groups of employees with very different expected term expectations may result in a less accurate result than an analysis that considers groups of employees with similar exercise behaviour (see Assumptions above).

- The reliability of early exercise parameters. Although lattice models allow for greater flexibility in modelling and valuing an award, the resulting values will be more reliable than more simplistic models such as the BSM model only if the input assumptions are reliable. The Board identified certain possible early exercise parameters – e.g. when a particular share price was reached or the volatility of the underlying shares. However, options may have been exercised in the past because of a range of complex factors that are not modelled easily. For example, an employee may exercise options to fund the purchase of a holiday home, children’s higher-level education, divorce etc. Use of historical experience to predict future behaviour using these factors may be unreliable.

- A holder’s decision not to exercise an option may not have been voluntary. For example, an option that was deeply out-of-the-money for long periods of its contractual life will not have been exercised because it was out-of-the-money. In such circumstances, a long historical holding period is not necessarily indicative that holders will hold future awards that are in-the-money for a similar length of time before exercising them. This may be a very important factor to consider when evaluating the exercise behaviour in respect of awards from entities whose share price suffered significant declines in value.

- Changes to the terms of an award. It may not be appropriate to apply exercise behaviour from an award with a specific set of contractual terms to an award whose terms differ – e.g. with respect to a market condition, contractual life etc.

- The volatility of the underlying shares. Options on shares with higher volatility may have earlier exercise than options on shares with lower volatility.

- The average length of time during which similar share options have remained outstanding in the past. (IFRS 2.B18)

Vesting and non-vesting conditions

Service and non-market performance conditions are not considered in estimating the value of an individual share or share option but are considered in estimating the number of instruments expected to vest (see Basic principles in Employee equity settled share-based payment).

Market conditions and non-vesting conditions are considered in estimating the fair value of an individual share or share option. Market conditions can be modelled using lattice models or Monte Carlo simulations, as discussed below, but not using the BSM model.

Non-vesting conditions that are based on prices available in a market – e.g. commodity prices – can be valued by simulating the underlying share price and the reference price. A complication is that these simulations are not independent and a simulation of the reference instrument – e.g. the commodity – should take account of the share price simulation, or vice versa.

Complicated techniques – e.g. Cholesky’s decomposition – can be employed in such simulations.

Non-vesting conditions that are not price-based – e.g. a requirement to hold underlying shares to retain a separate share option award – are not readily modelled and should be based on entity-specific or industry estimates.

Restrictions on transferability

A share-based payment arrangement may include restrictions on transferability that restrict the recipient from selling an award. Such restrictions may be categorised as either pre-vesting or post-vesting restrictions – i.e. restrictions that restrict a holder from disposing of an award before it vests or post-vesting restrictions that apply even once an award has vested.

Pre-vesting restrictions are not considered in valuing an award but post-vesting restrictions are. (IFRS 2.B8, BC153-BC169)

A discount that is applied to reflect the effect on the value of a share because the share cannot be traded readily either because the shares are not traded publicly or because they are subject to a transfer restriction is referred to as a ‘discount for lack of marketability’.

Discounts for lack of marketability are often applied for factors other than restrictions in a share-based payment arrangement – e.g. restrictions on transferability are often imposed on shareholders in private entities.

A share that has a limitation or restriction on transferability is less valuable than a share that is freely traded. However, quantifying the level of such a discount is difficult. Moreover, if a non-quoted share is subject to a post-vesting restriction, then care should be taken to avoid a double count of a lack of marketability discount – i.e. a discount for lack of marketability may have been applied already to reflect the fact that the share is not publicly quoted and is therefore less marketable than a quoted share.

In such circumstances, an incremental discount may apply for the post-vesting restriction but the level of such a discount should reflect the fact that a discount has already been applied in arriving at the value of a share.

In November 2006, the Interpretations Committee considered adding an issue to its agenda related to the fair value measurement of post-vesting transfer restrictions.

The specific issue was whether an approach to estimate the value of shares issued only to employees and subject to post-vesting restrictions could look solely or primarily to actual or synthetic markets that consisted of transactions between an entity and its employees in which, for example, prices reflected an employee’s personal borrowing rate.

Although it did not add the issue to its agenda, the Interpretations Committee noted several requirements of IFRS 2 that highlighted that value from an employee’s perspective was not the measurement objective, and that consideration should be given to actual or hypothetical transactions with actual or potential market participants.

It also noted that when the shares are traded actively in a deep and liquid market, post-vesting transfer restrictions may have little, if any, effect on the price that a knowledgeable, willing market participant would pay for those shares.

There are several methods used to estimate the level of a discount for lack of marketability, as discussed below. The estimation of a marketability discount should consider the specific characteristics of the entity and of the restriction, including the volatility of the value of the entity, the length of the restriction etc.

- Option pricing or derivative models: Some have sought to use options or other derivatives to quantify discounts for lack of marketability. This appears intuitively attractive because some of the inputs into option pricing models are also factors that would be considered by an investor in estimating a discount for lack of marketability – e.g. the length of the restriction, the volatility of the underlying shares etc. It has been suggested that an at-the-money put option can be used to quantify a marketability adjustment. This assumes that the value of the put option is equal to the value of the restriction and, implicitly that the value of a restricted share with a put option is equal to the value of an unrestricted share. However, the restricted share plus the put option is more valuable on a cash flow basis than an unrestricted share because the put option essentially eliminates the downside on the share while the unrestricted share would still have risk – i.e. the expected cash flows of the restricted share and the put option are greater than the cash flows on the unrestricted share. Therefore, although the value of an option is influenced by some of the same factors that affect the level of a marketability discount, option valuation techniques cannot provide an exact quantification of such a discount.

- IPO studies: These studies compare the prices at which shares were issued by an entity before an IPO with the entity’s subsequent IPO price. They quantify the discount for lack of marketability as the difference between the pre- and post-IPO prices. Potential weaknesses in this approach include that some of the pre-IPO transactions included in the studies may have been with related parties and that changes in an entity’s circumstances and prospects and/or investment markets may have contributed to any changes in value. It is not appropriate to apply average discounts from IPO studies without considering the specific facts and circumstances of an entity.

- Restricted share studies: Restricted share studies compare the prices at which registered shares in entities trade with the prices at which unregistered shares trade. In US equity markets, a public entity may have registered and unregistered shares. The latter are less marketable than the former because they can be sold only to qualified investment buyers. Differences in prices between registered and unregistered securities are attributed to the latter’s reduced marketability and such differences are used as a basis for estimating the level of a marketability discount. The level of discounts reported in these studies has varied both over time and within studies, depending on the characteristics of the entities involved. Their application to estimating post-vesting restrictions should be carefully considered and supported. It is not appropriate to apply average discounts from restricted share studies without considering the specific facts and circumstances of an entity.

In estimating or evaluating a marketability discount, it is useful to note that there is no difference between the underlying cash flows on a restricted share and those on an unrestricted share. A large marketability discount implies that a holder of a restricted share has a significantly higher required return than a holder of an unrestricted share. For example, a holder of an unrestricted share in Company B requires an annual rate of return of 10 percent.

Assuming that Company B does not pay a dividend, this return is expected to result from a capital gain from an increase in the share price – e.g. an increase to 110 after one year (100 x (1 + 10 percent)). If a restriction of 40 percent was applied to value a restricted share in Company B, then the current price of a restricted share would be 60 – i.e. 100 x (1 – 40 percent).

If the restriction expires in one year, at which stage the share is equal to other unrestricted shares, then the implied current required annual return on a restricted share would be 83 percent per annum (110 / 60 – 1). This indicates that the discount is too large.

Annualreporting provides financial reporting narratives using IFRS keywords and terminology for free to students and others interested in financial reporting. The information provided on this website is for general information and educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice. Use at your own risk. Annualreporting is an independent website and it is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or in any other way associated with the IFRS Foundation. For official information concerning IFRS Standards, visit IFRS.org or the local representative in your jurisdiction.

Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share option

Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share option

Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share option

Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share option

Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share options Fair value employee share option