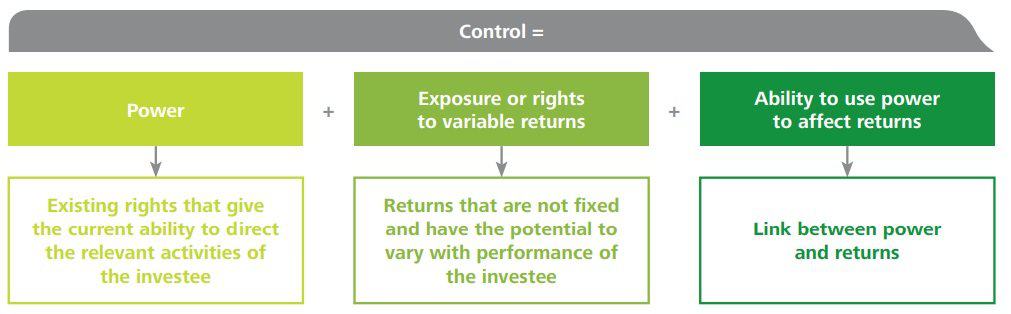

Consolidated definition

Consolidated definition is all about IFRS 10 Consolidated financial statements. Key in consolidated definition is:

- Control – To establish principles for the presentation and preparation of consolidated financial statements when an entity (the parent) controls one or more other entities (subsidiary(ies).

- The act of consolidation – combine assets, liabilities, equity, income, expenses and cash flows of the parent and its subsidiary(ies). Offset (eliminate) the parent’s investment in each subsidiary with its portion of equity of the subsidiary. Eliminate in full all intra-group transactions and balances, the parent and its subsidiaries must have and apply uniform accounting policies, if not, alignment adjustments must be quantified and posted, consolidation begins from the date the investor gains control of an investee and ceases when the investor loses control of an investee, and reporting dates cannot vary by more than 3 months. Here is this part.

- Special situations:

- Principal versus agent – An investor with decision making rights therefore has to determine whether it is a principal or an agent.

- ‘De facto agents’ – When assessing control, an investor needs to consider the nature of its relationship with other parties. In doing so the investor must consider whether those other parties are acting on the investor’s behalf (i.e. they are ‘de facto agents’). Such a relationship need not have a contractual arrangement.

Control

1 Power

1.1 Relevant activities Q&A

Question 1 – Assessing power when different investors control activities in different periods

An investor has power over an investee when the investor has existing rights that give it the current ability to direct the relevant activities of the investee (IFRS 10.10). Can an investor have power currently if its decision-making rights relate to an activity that will only occur at a future date?

X and Y set up a new company to construct and operate a toll road. X is responsible for the construction of the toll road, which is expected to take two years. Thereafter, Y has authority on all matters related to toll road operation. Is it possible for Y to have power over the company during the construction phase although X is responsible for construction and has authority to make decisions that need to be made currently?

Answer

Y may have power currently even though it cannot yet exercise its decision-making rights. The investor that has the ability to direct the activities that most significantly affect the returns of the investee has power over the investee (IFRS10.B13). The criteria in IFRS 10.B13 example 1 should be applied, which include consideration of:

- the purpose and design of the investee;

- the factors that determine profit margin, revenue and value of the investee. For example, the construction of the road may be under the supervision of the national roads authority. X is contracted to build the road under government supervision and, subject to audit, will recover its costs plus a specified percentage of margin. That margin will be returned through adjustment of the amount of tolls that will flow to X, so that X has first call on the cash flows generated by tolls. Y will manage the toll road operations, including maintenance, and will have be able to claim a management fee equivalent to any residual cash in the entity after all operating expenses have been paid, including payments to X. Y has the ability to set tolls. Alternatively, the arrangement could set out that the government regulates the tolls that can be charged with little variation in expected revenue but gives the investee more discretion over how the toll road is constructed, with X and Y sharing equally in the net cash flows of the investee;

- the effect on the investee’s returns resulting from each investor’s decision-making authority with respect to the factors in b); and

- investors’ exposure to variability of returns.

Question 2 – Re-assessment of power -When should an investor reassess control?

Assume the same fact pattern as in question 1, except that:

- two years have passed and the toll road has been fully constructed; and

- Y has entered bankruptcy, and X has assumed management of the toll road operations and is in discussions with the national roads authority to continue managing those operations.

Should X reassess whether it has control of the investee in this situation?

Answer

Yes, X should make this reassessment because there has been a change that affects the power criterion (IFRS 10.B80).

Question 3 – Can decisions made when an entity is formed be considered as relevant activities?

A structured entity (SE) was set up by a sponsoring bank to invest in bonds. The most important activity that affects the returns of the SE is the bond selection process. The bonds were selected upon set-up of SE by the sponsoring bank, and the incorporation documents state that no further bonds may be purchased. No further bond selection decisions are therefore required after the SE is set up.

Does the sponsoring bank have power over the SE solely by virtue of its power to select the bonds in which the SE invests?

Answer

Asset selection, on its own, is unlikely to give the sponsoring bank power in this scenario. The bonds cannot be replaced, so the power to select bonds (the relevant activity) ceased when the SE was established. However, the sponsoring bank’s active involvement in the design of the SE indicates that the bank had the opportunity to give itself power.

replaced, so the power to select bonds (the relevant activity) ceased when the SE was established. However, the sponsoring bank’s active involvement in the design of the SE indicates that the bank had the opportunity to give itself power.

All of the contractual arrangements related to the SE and other relevant facts and circumstances should be carefully assessed to determine if the bank has power over the SE (IFRS 10.B51). Power might arise from rights that are contingent on future events (see Question A7).

1.2 Potential voting rights Q&A

Question 4 – Can an option provide power when the option holder does not have the operational ability to exercise?

Investors X and Y own 30% and 70% respectively of a manufacturing company (‘Investee’). Investee is controlled by voting rights, manufactures a specific product for which the patent is owned by Y, and is currently managed by Y. X has an out-of-the-money call option over the shares held by Y.

The patent used by Investee will revert to Y if the call option is exercised, unless there is a change in control of Y, Y breaches the terms of the contract between the parties or Y enters bankruptcy. Investee cannot manufacture the product without Y’s patent, which is not replaceable. Neither party expects the call option to be exercised.

The purpose of the call option is to allow X to take control of Investee in exceptional Does the option provide X with power over Investee?

Answer

The option held by X is unlikely to be regarded as substantive. There are substantial operational barriers to the exercise of the call option by X. Further, X will not obtain benefits from the exercise of the call option absent the occurrence of one or more of the events described above.

The design of the call option suggests that the call option is not intended to be exercised (IFRS 10.B48). The option is therefore unlikely to confer power upon X.

Question 5 – Can an option provide power when the option holder does not have the financial ability to exercise the option?

Investors X and Y own 30% and 70% respectively of a company (‘Investee’) that is controlled by voting rights. X has a currently-exercisable, in-the-money call option over the shares held by Y. However, X is in financial distress and does not have the financial ability to exercise the option. Investee is profitable. Does the option provide X with power over Investee?

Answer

A currently exercisable in-the-money option is likely to convey power. X may not be able to exercise the option itself without seeking finance from a third party or might exercise the option and immediately re-sell its interest in Y.

If X could sell the option itself or otherwise obtain economic benefits from the exercise, the option will provide power of the Investee. An option that was out-of-the-money might mean there are significant barriers that would prevent the holder from exercising it [IFRS 10.B23(c)].

An option is therefore generally not substantive if it is not possible for the option holder to benefit from exercising it.

The purpose and design of such an option also needs to be considered (IFRS 10.B48).

Question 6 – Can an option provide power if it is out of the money?

Investors X and Y hold 30% and 70% respectively of a company (‘Investee’) that is controlled by voting rights. X has a currently-exercisable, out-of-the-money call option over the shares held by Y. Can the option provide X with power over the Investee?

Answer

Yes, such an option can provide X with power if it is determined to be substantive. This will require judgement based on all of the facts and circumstances. The relevant considerations are set out below.

X must benefit from the exercise of the option in order for it to be substantive (IFRS 10.B23(c)). The option is out of the money, which might indicate that the potential voting rights are not substantive (IFRS 10.B23(a)(ii)).

However, X may benefit from exercising the option even though it is out of the money. X might achieve other benefits − such as synergies from exercising the call option – and might, overall, benefit from exercising the option. The option is likely to be substantive in those circumstances (IFRS 10.B23c).

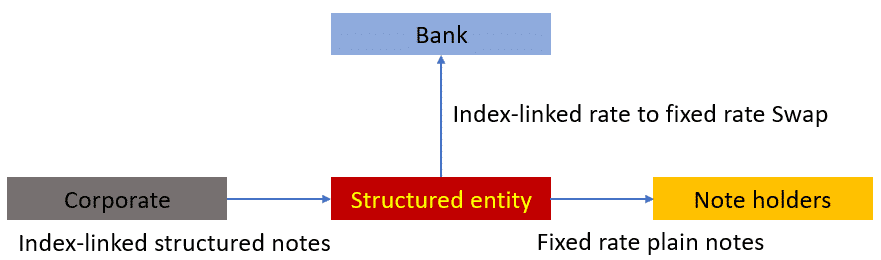

1.3 Structured entities Q&A

A structured entity is one that has been designed so that voting or similar rights are not the dominant factor in deciding who controls it (IFRS 12 Appendix A). For such entities, the criteria in IFRS 10.B51 to B54 should be applied in order to determine which investor, if any, has power.

Many structured entities may run on ‘auto-pilot’ such that no ongoing decisions need to be made after the structured entity has been set up. The assessment of power may be challenging for such entities, as there appear to be no significant decisions over which power is required.

entity has been set up. The assessment of power may be challenging for such entities, as there appear to be no significant decisions over which power is required.

IFRS 10.10 requires an investor to have the current ability to direct the relevant activities of the investee in order to have control.

If there are truly no decisions to be made after an entity has been set up, none of the investors have such a ‘current ability to direct’ and so no one would consolidate the investee. However, this assessment must be made carefully after considering all relevant factors including those set out below. In our view, such entities are expected to be rare.

The purpose and design of the structured entity should be considered when assessing control. Involvement in the purpose and design of a structured entity does not of itself convey power; it may indicate who is likely to have power (IFRS 10.B17 andB51).

If decisions that significantly affect returns are required only if some trigger event happens (for example, default of receivables or downgrade of collateral held by the structured entity), these should be looked to in determining who has power, no matter how remote the triggering event is.

These decisions should be considered in light of the purpose and design of the entity and the risks that it was intended to pass on. For example, decisions regarding the management of defaulting bonds are more likely to be relevant activities when the structured entity was set up to expose investors to the bonds’ credit risk, no matter how remote default might be at inception of the vehicle.

The possibility that non-contractual power may exist should also be considered. It will be important to assess how any decisions over any relevant activities are actually made in practice (IFRS 10.B18).

If the investee has some form of ‘special relationship’ with the investor, the existence of such a relationship could also suggest that the investor may have power (IFRS 10.B19).

Contractual arrangements such as call rights, put rights and liquidation rights established at the investee’s inception should also be assessed. When these contractual arrangements involve activities that are closely related to the investee, these activities should be considered as relevant activities of the investee when determining power over the investee (IFRS 10.B52).

If an investor has an explicit or implicit commitment to ensure that an investee continues to operate as designed, this may also indicate it has power over relevant activities. Such a commitment may increase the investor’s exposure to variability of returns and thus give it an incentive to obtain rights sufficient to give it power (IFRS 10.B54).

Finally, if an investor has disproportionately large exposure to variability of returns, it has an incentive to obtain power to protect its exposure; the facts and circumstances should therefore be closely examined to determine if it has power (IFRS 10.B20).

Question 7 – Contingent power

Can an investor have power if it can make decisions only upon a contingent event but cannot make any decisions currently?

Answer

An investor may have power in this situation. When an investor can direct an activity that will only occur in the future upon the occurrence of an event, that power should be considered even before the occurrence of that event (IFRS 10.B13; IFRS 10 example 1).

Contingent power is a key consideration in assessing who controls those structured entities where no decisions may be required or permitted unless the contingent event occurs (IFRS 10.B53). Contingent power is not necessarily protective only (IFRS 10.B26).

Question 8 – Can reputational risk give control?

A bank sets up a structured entity (SE) to acquire and hold pre-specified financial assets that the entity purchases from traded markets, and to issue asset-backed securities to investors. The bank has no further interest in, or decision-making rights over, the SE once it is set up.

However, the bank’s reputation will suffer if the SE fails. The bank will, in such circumstances, consider providing financial support to the SE, even though it has no obligation to do so, in order to protect its own reputation. How does reputational risk impact the conclusion on control?

Answer

Reputational exposure may create an implicit commitment for the bank to ensure that the SE operates as designed; however, this alone does not provide conclusive evidence that the bank has power (IFRS 10.B54). The bank was also involved in the design and set-up of the SE; however, this consideration, again, does not provide conclusive evidence of power (IFRS 10.B51).

If no other indicators of power exist, the bank is unlikely to control the SE. Reputational exposure on its own is generally not an appropriate basis for consolidation (IFRS 10.BC37).

However, all of the facts and circumstances should be carefully examined to establish whether the bank has control. Reputational exposure on its own is not sufficient to convey control, but it may increase the investor’s exposure to variability of returns and so give it an incentive to obtain rights sufficient to give it power (IFRS 10.BC39).

2 Exposure to variability Q&A

An investor must have exposure to an investee’s variable returns before the investor can meet the control criterion and consolidate the investee (IFRS 10.7).

‘Variable returns’ is a broad concept under IFRS 10; the standard sets out examples ranging from dividends to economies of scale, cost savings, tax benefits, access to future liquidity and access to proprietary knowledge (IFRS 10.B56 to B57). Even fixed interest and fixed performance fees are considered ‘variable’ returns, as they expose the investor to the credit risk of the investee because the amount recoverable is dependent on the investee’s performance.

To meet the criterion in IFRS 10.7(b), the investor’s involvement in the investee needs to be one that absorbs variability from the investee rather than contributes variability to it (IFRS 10.BC66 and 67).

For example, a party that borrows money from an investee at a plain vanilla interest rate contributes variability from its own credit risk to the investee; it is therefore not exposed to variable returns from the investee in the absence of other interests in it. Conversely, an ordinary shareholder in an investee absorbs fluctuations in the residual returns of the investee; the shareholder is therefore exposed to variable returns (absorbs variability).

Question 9 –What types of instrument absorb variability from an investee, and which instruments create variability in an investee?

Answer

Whether an instrument creates or absorbs variability may not always be that clear. We would generally expect the instruments in list I below to absorb variability of an investee and those in list II to create variability.

I. Instruments that in general absorb variability of an investee and therefore, if the holder’s degree of exposure to variable returns is great enough and the other tests in IFRS 10 are met, could cause the holder of such instruments to consolidate the investee:

- equity instruments issued by the investee;

- debt instruments issued by the investee (irrespective of whether they have a fixed or variable interest rate);

- beneficial interests in the investee;

- guarantees of the liabilities of the investee given by the holder (protects the investors from suffering losses);

- liquidity commitments provided to the investee; and

- guarantees of the value of the investee’s assets.

II. Instruments that generally contribute variability to an investee and therefore do not, in themselves, give the holder variable returns and cause the holder of such instruments to consolidate the investee:

- amounts owed to an investee;

- forward contracts entered into by the investee to buy or sell assets that are not owned by it;

- a call option held by the investee to purchase assets at a specified price; and

- a put option written by the investee (transfers risk of loss to the investee).

Question 10 – Does a contract with an entity create or absorb variability?

A structured entity (SE) holds C2m of high-quality government bonds. The SE enters into a contract whereby − in return for an upfront premium from the contract counterparty ‘A’ − the SE agrees to pay A C2m if there is default on a specified debt instrument issued by an unrelated company (Z). The SE has no other assets or liabilities, and is financed by equity investments from investors.

SE was set up for the purpose of entering into the contract with A to protect A against Z’s default on a specified debt instrument and to expose SE’s investors to the credit risk of Z.

A is potentially exposed to the credit risk of SE if Z defaults on a specified debt instrument. Does this mean that A has exposure to variable returns of SE through its purchased credit default swap (IFRS 10.7b)?

Answer

Yes, A does have exposure to variable returns of SE through its potential exposure to SE’s credit risk. However, this credit exposure is likely to be small relative to the credit risk of Z, given the quality of the government bonds.

Additionally, the SE is financed by equity investors and has no other liabilities, which reduces the credit risk to which A is potentially exposed. The contract is likely to have contributed more variability into the SE than it absorbs and is unlikely, on its own, to cause A to consolidate the SE.

Further, the purpose and design of SE is to transfer Z’s credit risk to SE, not to transfer the SE’s exposure to government bonds to A. Such a purpose and design supports a conclusion that the contract with A was designed primarily to transfer risk into the SE.

It is therefore unlikely the contract would cause A to consolidate the SE.

Question 11 – What assets should an investor look to in assessing control?

The assets recorded by an entity for accounting purposes do not always correspond to assets that are legally owned by the entity. The assessment of control could differ depending on whether the accounting or legal assets are considered. Should an entity focus on accounting or legal assets or on something else?

A Seller transfers legal title to receivables with a principal amount of C100 to a structured entity (‘Buyer SE’). In return, Buyer SE pays C93 cash and agrees that if it collects more than C93 of principal on the underlying receivables, it will pay the excess to the Seller.

The Seller therefore remains exposed to the risk that the underlying receivables may not be collected in full, up to an amount of C7. It has been assessed that the exposure created by this deferred consideration of C7 causes the Seller to retain substantially all of the risks and rewards of those receivables under IAS 39.

The Seller cannot therefore derecognise those receivables under IAS 39; and the Buyer SE, correspondingly, cannot recognise those receivables (IAS 39.AG50). Instead, the Buyer SE records a receivable from the Seller.

From a legal perspective, the Buyer SE owns 100% of the underlying receivables, of which the Seller is exposed to C7. From an accounting perspective, the Buyer SE has a receivable due from the Seller − that is, the Seller is a debtor of the Buyer SE, and the Seller is not therefore exposed to the variability of the Buyer SE.

Does the Seller have exposure to variability of Buyer SE for purposes of assessing control under IFRS 10?

Answer

Yes, the Seller has exposure to variability of Buyer SE.

IFRS 10 requires a consideration of the purpose and design of an entity (IFRS 10.B5), which includes consideration of the risks to which the investee was designed to be exposed, the risks it was designed to pass on to the parties involved with the investee, and whether the investor is exposed to some or all of those risks (IFRS 10.B8).

It is therefore necessary to look at the underlying risks to which the Buyer SE is exposed and the risks that the Buyer SE passes on to investors. This assessment of risks should be based on an assessment of the economic risks of the Buyer SE.

Economically, the Buyer SE is exposed to all the risks of the receivables, but some of those risks are passed on to the Seller via the deferred consideration mechanism. The Seller is therefore exposed to variability of the Buyer SE. The Seller is also potentially exposed to the credit risk of the Buyer SE (for example, if the Buyer SE collects all the monies from the underlying receivables but is unable to pay out the last C7 to the Seller due to unforeseen circumstances).

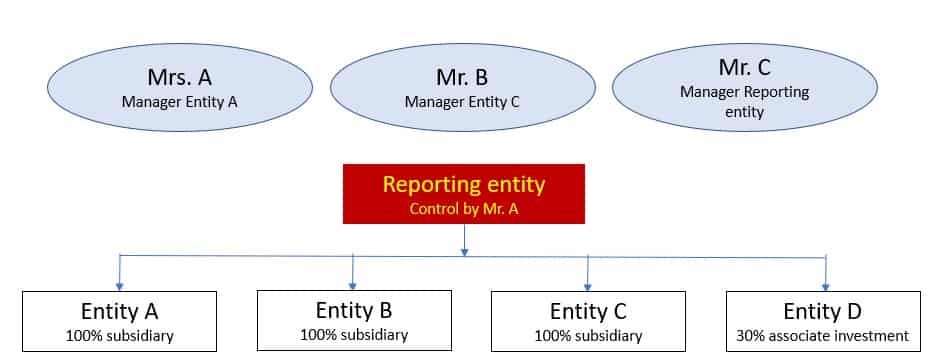

3. Link between power and returns Q&A

An investor with decision making rights has to determine whether it is a principal or an agent

An agent is defined as ‘a party primarily engaged to act on behalf and for the benefit of another party or parties (the principal(s)) and therefore does not control the investee when it exercises its decision making authority’

Thus, sometimes a principal’s power may be held and exercisable by an agent, but on behalf of the principal. An investor that is an agent does not control an investee when it exercises decision making rights delegated to it.

Principal-agent analysis

Certain decision-makers may be obligated to exercise their decision powers on behalf of other parties and do not exercise their decision powers for their own benefit. IFRS 10 regards such decision-makers as ‘agents’ that are engaged to act on behalf of another party (the ‘principal’).

A principal may delegate some of its power over the investee to the agent, but the agent does not control the investee when it exercises that power on behalf of the principal (IFRS 10 para B58). Power normally resides with the principal rather than the agent (IFRS 10 para B59).

There may be multiple principals, in which case each of the principals should assess whether it has power over the investee (IFRS 10.B59). An agent does not control and so will not consolidate the investee.

The overall relationship between the decision-maker and other parties involved with the investee must be assessed to determine whether the decision-maker acts as an agent. The standard sets out a number of specific factors to consider:

- The decision-maker is an agent if a single party can remove them without cause (IFRS 10.B65).

- The decision-maker cannot be an agent if remuneration is at other than normal market terms (IFRS 10.B69-B70).

- The scope of the decision-maker’s authority over investee may be wide and indicate that the decision-maker may have power; or narrow, pointing to the converse (IFRS 10.B62-63).

- Substantive rights held by other parties may indicate that the decision-maker is an agent (IFRS 10.B64-67).

- The magnitude and variability of the decision-maker’s remuneration may indicate that he is acting on his own behalf rather than on behalf of others (IFRS 10.B68).

Similarly, the magnitude and variability of the decision-maker’s exposure to returns from other interests in the investee may indicate that he is acting on his own behalf rather than on behalf of others (IFRS 10.B71-72).

Question 12 – Determination of the principal

IFRS 10.B59 states “…In situations where there is more than one principal, each of the principals shall assess whether it has power over the investee by considering the requirements in paragraphs B5-B54…”.

A decision-maker (a fund manager) is determined to be an agent in relation to the fund it manages, in which there are multiple investors. What considerations should be looked to in determining which (if any) of the investors should consolidate the fund?

Investors A, B and C invest in 15%, 30%, and 55% respectively of a fund that is managed by an external fund manager. The fund manager has wide powers to make investment decisions, and the investors cannot direct or veto these decisions. The fund manager can be removed only by a unanimous vote from all three investors and has been assessed to be an agent under IFRS 10.

Should investors A, B or C attribute the fund manager’s decision powers to themselves when they each consider whether they have power over the fund?

Answer

An agent does not control an investee (IFRS 10.B58). The manager does not therefore control the fund. Rather it is primarily acting on behalf of the other investors (the principals).

However, although an agent “is a party primarily engaged to act on behalf of and for the benefit of another party or parties (the principal(s))”, this does not necessarily mean that any one of the principals controls the entity.

Where there are multiple principals, each principal should assess whether it has power over the investee by considering all the factors in the consolidation framework (IFRS 10.B59) − that is, power, exposure to variable returns and the ability to use power to affect returns.

For example, if a fund has many widely-dispersed investors all of whom have a small holding, and the investors do not have substantive rights to remove the fund manager or to liquidate the fund nor to direct the decisions made by the fund manager, then none of the investors would have control.

Conversely, if a single investor has a large holding in the fund and the other investors are dispersed and the investor has the practical ability to remove the fund manager or direct the decisions it makes, then it is likely that the investor has power and controls the fund.

Therefore, with regards to the example fact pattern, the investors should not attribute the fund manager’s decision powers to themselves. The fund manager is an agent for all three investors. As the agent acts for multiple principals, each of the principals must assess whether it has power (IFRS 10.B59).

None of the investors has the unilateral power to direct or remove the fund manager. Therefore, none of them on their own have the ability to direct the relevant activities of the fund (IFRS 10.B9).

Question 13 – Is an annual re-appointment requirement considered to be a substantive right?

Substantive removal rights held by other parties may indicate that the decision-maker is an agent. Is a requirement to re-appoint the decision-maker on an annual basis an example of a substantive removal right?

Fund X is managed by a fund manager, which is required to be appointed by the board of Fund X on an annual basis. All of the members of the board are independent of the fund manager and appointed by other investors. The fund management service can be performed by other fund managers in the industry.

Effectively, the annual appointment requirement provides the board with a mechanism to replace the fund manager if necessary. Is the annual appointment requirement a substantive removal right?

Answer

Yes, this is likely to be a substantive removal right (IFRS 10 example 14C). The fund manager should consider the removal right along with other relevant factors, including its fees and other exposure to variable returns, in order to determine whether it is an agent.

Question 14 – Is a removal right with a one-year notice period requirement a substantive removal right?

Fund X is managed by a fund manager, which can be removed by the board of Fund X with a one-year notice period. All of the members of the board are independent of the fund manager and appointed by the investors of Fund X; the majority are independent of the fund manager. The fund management service can be performed by other fund managers in the industry. Is the removal right substantive given that a one-year notice period is required?

Answer

In our view, a positive appointment of an asset manager for a limited period (see Question C2) is different from an indefinite contract with a removal right exercisable with a notice period. The reappointment right creates a mechanism by which the asset manager’s performance is positively considered. A removal right is only exercised from the point that the service is unsatisfactory.

It may be assumed that where an asset manager is appointed for one year, its services will not be unsatisfactory on the first day of appointment. Our view is that a one-year re-appointment right is more likely to be substantive than a one-year notice period because the long notice period may provide a barrier to its exercise.

The guidance on substantive rights is relevant when considering notice periods. Questions that an asset manager should ask in assessing the impact of notice periods on the principal-agent determination include:

- How long is the notice period?

- Is there only a short window during which notice can be given?

- Will the decisions taken within the notice period significantly affect the returns of the fund?

Question 15 – Is an intermediate holding company an agent of its parent?

Holdco, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Parent, owns 100% of Opco, an operating company. The only business purpose of Holdco is to hold investments in Opco. Holdco issues listed debt and is required by local law to prepare consolidated financial statements where required by IFRS.

Is Holdco an agent or de facto agent of Parent (and therefore does not control Opco) if:

- Parent and Holdco have the same managing directors;

- Holdco’s managing directors are Parent’s employees; or

- Holdco is managed by a trust office that is contractually bound to act fully in accordance with Parent’s decisions?

Answer

No. A decision-maker is an agent/de facto agent only when it has been delegated those decision-making powers by another party. IFRS 10.B59 states: “An investor may delegate its decision-making authority to an agent on some specific issues or on all relevant activities. When assessing whether it controls an investee, the investor shall treat the decision-making rights delegated to its agent as held by the investor directly.”

Holdco controls Opco directly in all three scenarios, as it holds the shares in Opco, and Holdco’s management can dictate Opco’s policies through the voting power given by Opco’s shares.

Regardless of the degree of Parent’s representation or control of Holdco’s governing body, the direct investment in Opco and power over Opco are both held by the corporate entity Holdco. Any party that governs Holdco accesses that power by becoming a representative of Holdco. Similarly, any party that owns Holdco accesses the returns of Opco through Holdco.

As power over Opco belongs, in the first place, to Holdco rather than Parent, Parent has not delegated any power to Holdco; Holdco is not therefore an agent of Parent. As Holdco is also exposed to variability of Opco’s returns, Holdco should consolidate Opco.

Question 16 – Employees as de facto agents

Employees of the reporting entity may take on management roles in an investee. Are employees in key management  personnel (KMP) roles considered the de facto agents of a reporting entity, in relation to the reporting entity’s investees?

personnel (KMP) roles considered the de facto agents of a reporting entity, in relation to the reporting entity’s investees?

Entity X manages and has full decision-making authority over a fund. X grants performance-based awards to its KMP whereby they receive shares in the managed funds if certain conditions are met. X also requires that part of the KMP’s cash bonuses is invested directly in the funds. The KMP may also invest their own funds. X does not hold any direct interest in the fund.

As X does not have any direct interest in the fund (other than a management fee), this might suggest that X does not have significant exposure to variable returns. However, the KMP may in substance be holding their shares on behalf of X.

The right of the KMP to invest in the funds may be a form of compensation and so provide indirect benefits to X. This will impact both the exposure to variable returns criterion (IFRS 10.7b) and the principal-agent analysis (IFRS 10.7c, IFRS 10.B74) of control.

Do KMP act as de facto agents of X?

Answer

Judgement is required to assess whether:

-

the KMP might use their investments on behalf of X; or

-

the investments are the personal assets of the KMP, over which the reporting entity has no power.

This judgement should be made based on facts and circumstances, for example, the position of the KMP within the company; the reason KMP are holding those investments; whether those shares have vested (and whether the KMP could resign and retain their investments); whether the shares were granted by X or purchased using KMP’s own resources; any restrictions on transfers of those shares by KMP without X’s approval; and how KMP vote on those investments in practice.

If the KMP are de facto agents, their shareholdings will be attributed to X when deciding whether X should consolidate the fund.

Question 17 – If a decision-maker is remunerated at market rate, does this mean that it is an agent?

A fund manager (‘FM’) is given wide investment powers over an equity fund that it manages. The fund manager receives an annual fee of 2% of the net asset value of the fund, which is consistent with the fee structure of similar funds.

Can the fund manager conclude that it is an agent for fund investors and therefore does not control the fund, by virtue of the fact that it only receives market remuneration?

Answer

No, the fund manager cannot conclude that it is an agent on this basis alone.

The other factors in IFRS 10 must also be considered. For example, if the fund manager has a direct investment in the fund, that should be considered (IFRS 10. B71-72). The fund manager also needs to consider the magnitude and potential variability of its remuneration relative to the returns of the investee (IFRS 10.B68, B72).

An asset manager may choose to reduce its fee for relationship purposes if the returns of the fund are very low. This would preserve a return for the other investors and effectively increase the variability of the fund manager’s return. IFRS 10 examples 13 to 16 provide guidance on how to assess such exposure.

A fund manager is a principal if it accepts a fee structure that is not commensurate with the services provided and does not include only terms, conditions or amounts that are customarily present in arrangements for similar services and level of skills negotiated on an arm’s length basis (IFRS 10 B69).

However, the converse is not true − that is, the fact that remuneration is market-based is not sufficient to conclude that the fund manager is an agent (IFRS 10.B70).

However, a manager with no direct interest in a fund that receives a market-based fee is likely to be an agent.

Annualreporting provides financial reporting narratives using IFRS keywords and terminology for free to students and others interested in financial reporting. The information provided on this website is for general information and educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice. Use at your own risk. Annualreporting is an independent website and it is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or in any other way associated with the IFRS Foundation. For official information concerning IFRS Standards, visit IFRS.org or the local representative in your jurisdiction.

Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition

Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition Consolidated definition