1. From Boardroom to Border: When Governance Escapes the Firm

Tech entrepreneurs creating private states – Corporate governance was never designed for this.

Traditional governance frameworks—OECD principles, board structures, internal control systems, audit committees—assume a bounded entity: a company operating within the legal, fiscal and democratic infrastructure of a sovereign state. The company may be large, influential, even systemically important, but it remains subject to an external authority. The state is the referee. The company plays the game.

What happens when the players begin designing their own pitch?

Over the past decade, a subset of technology entrepreneurs and investors—primarily rooted in Silicon Valley’s libertarian ecosystem—has begun to experiment with something radically different: the creation of semi-autonomous zones, charter cities, network states and privately governed territories. These initiatives are not science fiction. They exist, attract capital, employ people, and in some cases host thousands of residents.

The Volkskrant analysis “Power and money are no longer enough for the tech bros – they want to found their own states” describes this phenomenon with journalistic precision, documenting projects such as Próspera (Honduras), Praxis Nation, and California Forever, and tracing the ideological roots back to figures like Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen.

From a governance perspective, these initiatives represent something far more consequential than eccentric billionaire hobbies. They signal a structural stress test for corporate governance itself. When economic power, technological capability, and ideological ambition converge, governance migrates—from the boardroom to the border, from internal control to constitutional design.

This article examines that migration. Read more on the BBC: The crypto bros who dream of crowdfunding a new country.

2. The Governance Paradox: Hyper-Control Internally, Radical Freedom Externally

One of the most striking contradictions in Big Tech governance is this:

The same entrepreneurs who build companies with extreme internal control, surveillance, and optimization advocate radical deregulation once they step outside the firm.

Inside Big Tech companies, governance is anything but libertarian. Decision rights are tightly centralized. Algorithms monitor performance continuously. Access rights, escalation protocols, and compliance mechanisms are sophisticated and unforgiving. Internal audit, risk management, and legal oversight are deeply embedded.

Yet when these actors speak about states, regulation, or democracy, the language flips. Governments are inefficient. Regulation is obsolete. Democratic processes are too slow for innovation. The solution, they argue, is not better governance—but exit.

Albert Hirschman famously framed responses to failing systems as exit, voice, or loyalty. These projects represent exit at scale. Instead of lobbying governments (voice) or reforming institutions (loyalty), tech elites design parallel jurisdictions where they can write the rules themselves.

Governance scholars should pause here. Because this is not deregulation—it is re-regulation, but with radically altered accountability structures.

3. Network States Explained: Governance Without a Demos

The ideological backbone of these initiatives is often referred to as the network state, a concept popularized by Balaji Srinivasan. The idea is deceptively simple:

-

Start with an online community bound by shared ideology.

-

Aggregate capital and talent.

-

Acquire physical territory.

-

Negotiate recognition from existing states.

-

Transition from digital network to sovereign entity.

In theory, this is governance-as-a-startup: lean, scalable, user-centric. In practice, it raises fundamental governance questions.

A state, unlike a company, derives legitimacy not from capital contribution or user adoption, but from citizenship, consent, and accountability. Boards can be replaced. Governments cannot be pivoted.

Projects like Próspera explicitly blur this boundary. Established as a Zone for Employment and Economic Development (ZEDE) in Honduras, Próspera operates with its own legal system, tax regime, and regulatory framework. Residents effectively opt into a parallel governance structure, one that prioritizes investor certainty over democratic participation.

The Volkskrant article notes that although Honduras formally abolished ZEDEs in 2022, Próspera continues to operate, highlighting the legal ambiguity and geopolitical friction inherent in such models.

From a governance standpoint, this is a red flag: rule of law without democratic anchoring.

4. The Corporate Governance Lens: Where the Framework Breaks

Let us apply a classic corporate governance lens.

Accountability

In listed companies, accountability flows upward (to the board) and outward (to shareholders, regulators, and society). In network states, accountability flows primarily to investors and founders. Residents are closer to customers than citizens.

Transparency

Corporate transparency is enforced through disclosure regimes, audit requirements, and market discipline. Network states often promise transparency, but without independent enforcement mechanisms. Who audits a state founded by its own financiers?

Checks and Balances

Modern governance relies on separation of powers. These projects concentrate legislative, executive, and judicial functions in compact governance structures designed for speed and efficiency. Efficiency, however, is the enemy of restraint.

Stakeholder Model

Corporate governance has gradually shifted from shareholder primacy toward stakeholder capitalism. Network states reverse this trend. Stakeholders without capital—workers, residents, local communities—have limited voice.

The metaphor here is biological: these systems resemble organisms with a powerful brain but an underdeveloped nervous system. They can act quickly, but they feel little pain when decisions harm peripheral stakeholders.

5. Case Study I – Próspera: Governance as a Product

Próspera markets itself as a governance innovation platform. Its value proposition mirrors that of enterprise software:

-

Regulatory efficiency

-

Legal certainty

-

Investor-friendly dispute resolution

-

Modular governance services

Residents can choose legal systems as if selecting software packages. Arbitration replaces courts. Contracts replace constitutions.

This is governance as a service (GaaS).

From a business perspective, it is elegant. From a governance perspective, it is dangerous.

Why? Because law becomes a product, and products are optimized for buyers, not for justice. The absence of political opposition, investigative journalism, and electoral pressure removes the friction that normally prevents abuse.

The Volkskrant analysis explicitly raises concerns about neocolonial dynamics: wealthy Western entrepreneurs experimenting with governance models in economically vulnerable regions.

Governance without friction may look efficient. It rarely proves resilient. Read the New York Times on this ‘land’ – The For-Profit City That Might Come Crashing Down.

6. Case Study II – Praxis Nation: Ideology Without Territory

If Próspera represents physical governance experimentation, Praxis Nation represents its ideological extreme.

Praxis exists primarily as a digital movement: an online community, capital pool, and aesthetic vision of a techno-futurist city-state. Its founders explicitly frame it as a civilizational reboot, blending libertarianism, futurism, and elite selection.

There is no functioning territory yet. But from a governance perspective, Praxis is arguably more revealing than Próspera.

Why? Because it exposes the cultural logic behind these projects.

Governance is not treated as a public good. It is treated as a design problem. Citizens are not equals; they are curated participants. Inclusion is not a right; it is a feature.

This is governance as architecture, not as democracy. Read more on Praxis Nation in Vanity Fair: Welcome to Praxis: The High-Tech, High-Testosterone Eden That Will Save the World.

7. The Historical Echo: Company States and Charter Empires

None of this is new.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC), the British East India Company, and other chartered enterprises exercised quasi-sovereign powers: taxation, military force, legal authority. They were accountable primarily to investors, not populations.

History’s verdict on these experiments is unambiguous: they generated wealth, but at enormous human and ethical cost.

Modern tech entrepreneurs often dismiss these comparisons as irrelevant. They argue that technology, transparency, and voluntary participation change everything.

Governance scholars should respond bluntly: tools change; power dynamics persist. Read more on the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company on Britannica.com

8. Why This Matters for Corporate Governance Today

Even if most of these projects fail, they matter profoundly for corporate governance for three reasons:

-

They redefine the ambition horizon of corporate power

Boards are no longer the ceiling. Sovereignty is. -

They expose the limits of existing governance frameworks

ESG, CSR, and stakeholder models assume state primacy. That assumption is weakening. -

They force regulators, auditors, and governance professionals to think beyond firms

When companies design jurisdictions, governance risk becomes geopolitical.

The uncomfortable truth is this: corporate governance is being outpaced by corporate ambition. Read more in our blog: Good Corporate Governance – Foundations of Trust and Accountability.

9. Metaphor: Governance Without Gravity

States provide gravity. They slow things down. They force negotiation. They absorb shocks. They create inertia.

Network states aim to eliminate gravity.

But systems without gravity do not stabilize. They drift. They fragment. They collide.

The question is not whether these experiments are innovative. They are.

The question is whether governance without gravity can endure.

10. California Forever: When Corporate Governance Dresses Up as Urban Planning

If Próspera and Praxis represent the libertarian edge of governance experimentation, California Forever represents its respectable cousin.

At first glance, California Forever looks different. Less crypto-utopian. Less anti-state rhetoric. More community-oriented language. The project—backed by Silicon Valley investors who quietly acquired vast tracts of land in Solano County—promises a walkable, green city with affordable housing, clean energy, and high quality of life.

Yet governance professionals should look past the marketing.

Because structurally, California Forever raises the same core question: who governs whom, and on whose mandate?

Unlike Próspera, California Forever does not seek legal autonomy. It operates within U.S. law. But its governance model is still profoundly corporate:

-

Land is aggregated by capital, not public mandate

-

Urban design precedes democratic representation

-

Governance emerges after investment, not before

This reverses the traditional sequence of city formation. Historically, cities emerge through population, commerce, political negotiation, and only then formal planning. California Forever flips that logic. The city is designed like a product roadmap, and governance becomes a downstream concern.

From a corporate governance perspective, this resembles a leveraged buyout of public space. Also read our blog on: AI and Corporate Governance – Vision, Technology and Trust in a Connected World.

11. Governance Risk Reframed: From Agency Problem to Legitimacy Gap

Classic corporate governance theory is obsessed with the agency problem: how to align management with shareholders. Network-state initiatives expose a different risk altogether:

The legitimacy gap.

These projects may be efficient, well-capitalized, and technologically sophisticated, but they struggle to answer a simple question:

Why should non-investors accept your authority?

In companies, legitimacy flows from ownership and contracts. In states, legitimacy flows from citizenship and consent. Network states sit awkwardly in between. Participation is framed as voluntary, but exit is rarely costless once livelihoods, housing, and social networks are embedded.

This is where governance theory collides with political philosophy. A system optimized for voluntary entry may still become coercive over time. Without democratic renewal mechanisms, governance calcifies around early adopters and capital providers.

The result is governance that is procedurally clean but substantively hollow.

12. Venture Capital as a Shadow Constitution

One underexplored dimension in the debate is the role of venture capital governance norms.

Venture capital is not neutral money. It brings with it:

-

Preference for speed over deliberation

-

Concentration of control through preferred shares

-

Exit-oriented time horizons

-

Founders’ control structures

These norms make sense in startups. They are toxic in governance systems meant to endure decades.

When VCs fund network states, they effectively write a shadow constitution. Decision rights are embedded in term sheets rather than charters. Dispute resolution prioritizes arbitration over public courts. Transparency is selective, not universal.

The Volkskrant article highlights how prominent investors such as Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, and Sam Altman are repeatedly linked to these initiatives, either directly or ideologically.

This matters because these individuals have already reshaped corporate governance through dual-class shares, founder control, and aggressive regulatory arbitrage. Network states represent the next iteration of that logic, not a break from it.

13. Regulatory Arbitrage, Elevated to Sovereignty

Corporate governance professionals are familiar with regulatory arbitrage: choosing jurisdictions with favorable tax, labor, or disclosure regimes. Network states elevate this from tactic to strategy.

Instead of selecting jurisdictions, they create them.

This has three systemic effects:

-

Race to the bottom, rebranded as innovation

Labor protections, environmental rules, and consumer safeguards are reframed as inefficiencies. -

Fragmentation of accountability

When disputes arise, responsibility is diffused across private entities, arbitration panels, and host states. -

Asymmetric power dynamics

Individuals negotiate with governance systems backed by billions in capital and legal sophistication.

The danger is not immediate collapse. The danger is normalization. Once these models gain legitimacy, traditional states face pressure to compete—by weakening their own governance standards.

This is not hypothetical. Special economic zones, charter cities, and investor courts already exert downward pressure on regulation globally.

14. The Audit Question: Who Audits a State?

For readers of annualreporting.info, this question deserves special emphasis.

In corporate governance, audit is the last line of defense. Independent assurance, professional skepticism, and standardized reporting underpin trust.

But network states systematically evade this logic.

-

There is no supreme audit institution

-

There is no independent public oversight

-

There is no electorate demanding transparency

Self-reporting replaces statutory disclosure. Arbitration replaces public jurisprudence. Private security replaces public law enforcement.

From an assurance perspective, these systems resemble unaudited conglomerates operating outside consolidated supervision.

For auditors, this raises an uncomfortable prospect: entities that look like governments, behave like companies, and are accountable to neither.

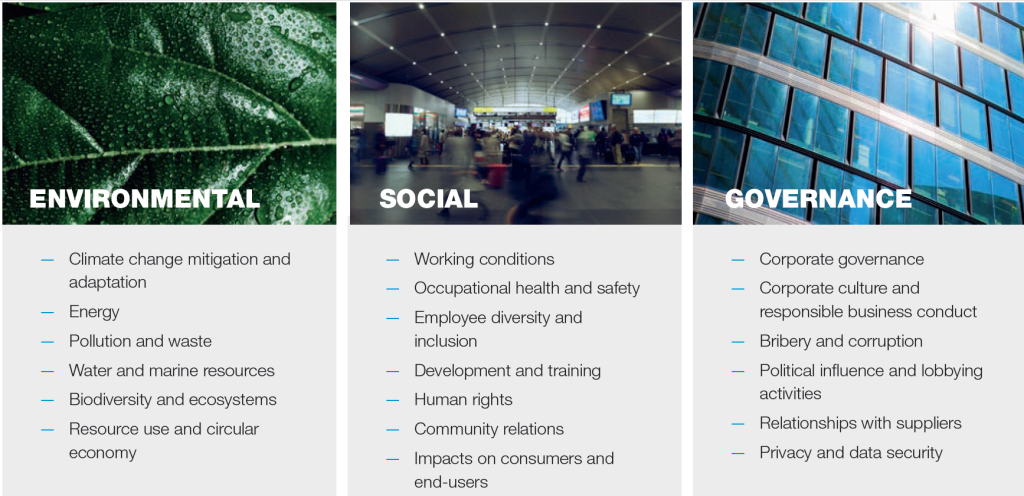

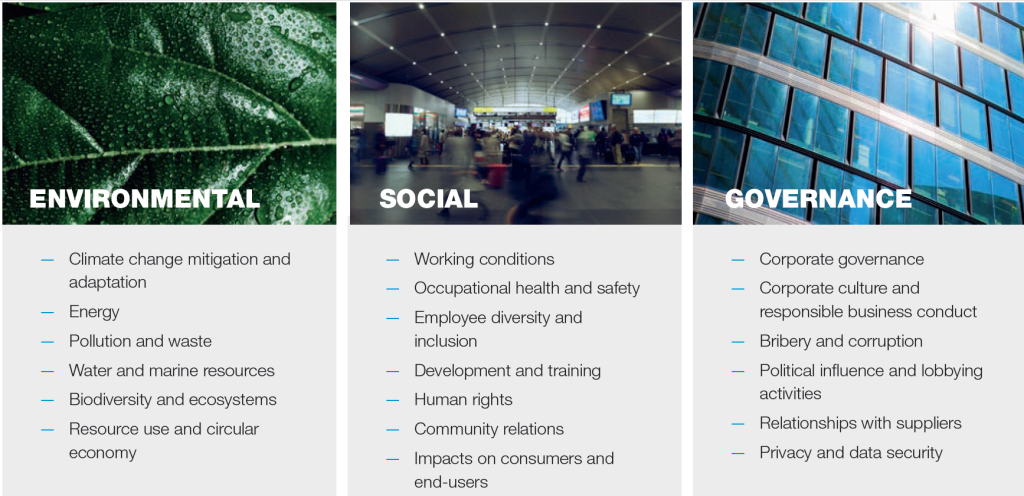

15. The ESG Mirage: Sustainability Without Society

Many network-state initiatives lean heavily on ESG language. Green cities. Smart infrastructure. Carbon neutrality. Technological solutions to urban decay.

Yet ESG without democratic governance is incomplete.

Environmental metrics can be optimized. Social metrics require voice. Governance metrics require power-sharing.

Without independent media, civil society, and political opposition, ESG becomes a branding exercise, not a governance framework.

This mirrors a broader trend in corporate ESG reporting: impressive dashboards disconnected from lived reality. Network states risk becoming the ultimate ESG simulacrum—beautiful on paper, brittle in practice.

16. Gender, Power, and the Invisible Hierarchy

Another governance blind spot deserves attention: who is absent.

Leadership narratives around network states are overwhelmingly male, techno-centric, and elite. The archetype is the founder-visionary, not the community builder. Governance literature teaches us that homogeneity increases risk—groupthink, blind spots, ethical drift.

Traditional states mitigate this through pluralism, however imperfectly. Network states, by design, select for alignment, not diversity.

The result is governance that is internally coherent but externally disconnected—a closed loop reinforcing its own assumptions.

17. The Illusion of Exit: Why “Voluntary” Governance Is Not Neutral

Proponents often argue that network states are benign because participation is voluntary. If residents dislike the rules, they can leave.

This argument misunderstands governance risk.

Exit is asymmetric. Capital exits easily. Individuals do not.

Jobs, housing, education, healthcare, and social ties create friction. Over time, voluntary systems acquire coercive characteristics—not through intent, but through structure.

Corporate governance learned this lesson decades ago. Employment contracts are voluntary. Power imbalances persist.

States learned it centuries ago. Citizenship is sticky.

Network states pretend otherwise.

18. The Bigger Picture: A Crisis of Trust, Not Just Governance

Ultimately, these experiments are symptoms, not causes.

They emerge from declining trust in public institutions, regulatory fatigue, and political polarization. Tech entrepreneurs are not wrong to observe that many governments struggle with complexity, speed, and innovation.

But replacing imperfect democracy with optimized technocracy is not governance reform—it is governance substitution.

And substitution always benefits those who control the substitute.

19. Metaphor Revisited: Governance as Infrastructure, Not Software

Governance is often compared to software—upgradable, modular, scalable. This metaphor is seductive and wrong.

Governance is infrastructure.

You can optimize traffic lights, but you cannot refactor a bridge while people are crossing it. You can innovate at the margins, but the load-bearing structures must endure stress, dissent, and time.

Network states treat governance like an app. States treat it like a bridge.

History suggests the bridge metaphor survives.

20. Where This Leaves Boards, Auditors, and Regulators

For governance professionals, the lesson is not to panic—but to adapt.

Boards must recognize that corporate ambition increasingly intersects with public authority. Auditors must expand their conception of public interest. Regulators must anticipate governance models that do not fit existing categories.

Above all, governance must reclaim its moral dimension. Efficiency without legitimacy is fragile. Innovation without accountability is unstable.

21. The Core Governance Question Reframed

At its core, the rise of network states and privately governed cities forces governance professionals to confront an uncomfortable but necessary question:

Is corporate governance still adequate when corporations begin to approximate states?

For decades, governance debates have revolved around improving internal mechanics: better boards, stronger controls, clearer accountability lines, enhanced disclosure. These tools were designed for entities operating within the institutional architecture of democratic states.

Network states invert that relationship. They place corporate logic around the state—or deliberately outside it.

This is not a marginal development. It represents a structural escalation of corporate power. And escalation always demands recalibration of oversight.

22. Why Existing Governance Frameworks Are Necessary but Insufficient

Let us be precise: traditional governance frameworks are not obsolete. They are simply incomplete.

OECD Principles

Designed for corporate accountability within functioning legal systems. They presuppose effective courts, regulators, and political institutions.

ESG Frameworks

Valuable for signaling intent and measuring impact, but weak on enforcement without sovereign backing.

Stakeholder Models

Conceptually strong, practically fragile when stakeholders lack voice, representation, or exit power.

Audit and Assurance

Powerful within statutory regimes; almost powerless in privately governed jurisdictions without public mandate.

Network states exploit these blind spots. They operate in the negative space between governance models—where responsibility diffuses and authority concentrates.

23. Governance Capture: When Design Replaces Deliberation

One recurring theme across all examined initiatives is design dominance.

Governance is treated as an engineering problem: optimize incentives, reduce friction, automate compliance. While this works for systems, it fails for societies.

Why? Because societies are not optimized systems; they are negotiated orders.

Deliberation, dissent, delay, and compromise are not inefficiencies—they are stabilizers. They absorb conflict before it becomes rupture.

Network states minimize these stabilizers. In doing so, they increase systemic risk while believing they are reducing it.

From a governance risk perspective, this is a classic case of local optimization producing global fragility.

24. Lessons for Boards: Power Always Expands Beyond Intent

Boards often assume that corporate influence ends at the firm boundary. That assumption no longer holds.

Large technology companies shape:

-

Information flows

-

Labor markets

-

Political discourse

-

Regulatory agendas

-

Urban development

Network-state initiatives are simply the most explicit manifestation of this influence.

Boards must therefore ask a new category of questions:

-

Are we creating dependencies that resemble public infrastructure?

-

Are we exercising power without corresponding accountability?

-

Are our governance structures equipped for societal impact, not just financial performance?

Failure to ask these questions does not eliminate responsibility—it merely delays reckoning.

25. Lessons for Auditors: The Expanding Public Interest

Auditing has always evolved in response to power asymmetries. The profession emerged because trust could no longer be assumed.

Network states represent a new asymmetry: private governance without public audit.

Auditors should not attempt to audit states. But they must recognize when corporate structures begin to substitute public functions.

This requires:

-

Broader interpretations of public interest

-

Greater skepticism toward “voluntary governance” claims

-

Courage to question legitimacy, not just compliance

Silence in the face of power expansion is not neutrality. It is acquiescence.

26. Lessons for Regulators: Governance at the System Boundary

Regulators face a conceptual challenge. Network states do not fit existing categories. They are not companies. They are not governments. They are hybrids.

Regulatory responses must therefore shift from entity-based supervision to function-based oversight.

The key question should not be what are you?

It should be what power are you exercising?

Whenever private entities exercise:

-

Rule-making authority

-

Adjudication power

-

Coercive control over livelihoods

-

Territorial governance

Public oversight must follow.

Anything less invites regulatory arbitrage at civilizational scale.

27. Why This Is Not Anti-Innovation

Critics often frame governance concerns as resistance to innovation. This is a false dichotomy.

Innovation thrives within constraints. Markets require rules. Trust requires enforcement. Freedom requires structure.

The most successful economies are not those with the weakest governance—but those with predictable, legitimate, and adaptive governance.

Network states confuse speed with progress, autonomy with legitimacy, and design with justice.

History suggests that societies which forget these distinctions do not innovate faster—they fracture sooner.

28. The Moral Dimension: Governance Is Ultimately About Power

Strip away the jargon, and governance reduces to a simple truth:

Who decides, for whom, and under what constraints?

Network states concentrate decision-making power in narrow circles defined by capital, ideology, and technical expertise. They externalize risk to residents, host states, and future generations.

This is not inherently malicious. But it is inherently unbalanced.

Good governance exists precisely to correct imbalance.

29. A Forward-Looking Governance Agenda

What, then, must governance become?

1. From Firm-Centric to Power-Centric

Governance frameworks must track power accumulation, not just legal form.

2. From Voluntary to Enforceable

Soft commitments are insufficient where exit is asymmetrical.

3. From Speed to Resilience

Efficiency metrics must be balanced with legitimacy metrics.

4. From Design to Deliberation

Governance must remain a human process, not a technical abstraction.

5. From National to Transnational

Private power no longer respects borders. Governance must adapt accordingly.

30. Final Metaphor: The Governor and the Engine

The word “governance” shares its root with “governor”—the device that prevents an engine from destroying itself by running too fast.

Network states remove the governor.

The engine accelerates. Performance spikes. Control tightens.

Until it doesn’t.

Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech billionaires and sovereignty Private cities governance risks Corporate power beyond the state

31. Conclusion: Why We Still Need the State

States are slow. Messy. Imperfect.

They are also the only institutions designed to absorb disagreement without collapse.

Corporate governance can improve firms. It cannot replace citizenship. Technology can enhance governance. It cannot substitute legitimacy.

When tech entrepreneurs dream of their own states, they reveal not just ambition—but a misunderstanding of what governance is for.

Governance is not there to enable power.

It is there to restrain it.

And that remains its most vital function.

FAQ’s – Network states and corporate governance

Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states

FAQ 1 – What exactly are “network states” and why do they matter for corporate governance?

Network states are privately initiated governance structures that originate as online communities, accumulate capital and members, and eventually seek physical territory and political recognition. Unlike traditional states, they are not founded through democratic processes but through capital formation, contractual participation, and ideological alignment.

From a corporate governance perspective, network states matter because they apply corporate logic to public authority. Decision-making resembles board governance rather than parliamentary democracy. Power is often concentrated among founders and investors, accountability flows upward to capital providers, and participation is framed as voluntary rather than civic.

This challenges existing governance assumptions. Corporate governance frameworks presuppose that firms operate within sovereign states that provide legal enforcement, democratic legitimacy, and public oversight. Network states invert this relationship by embedding governance inside private structures and treating law as a configurable service.

The relevance for governance professionals lies not in whether these projects succeed, but in what they reveal: the expanding ambition of corporate power and the inadequacy of traditional oversight models when private entities begin exercising quasi-sovereign authority. Network states expose the boundary where corporate governance ends—and where it must evolve.

FAQ 2 – How do privately governed cities differ from traditional special economic zones?

Special economic zones (SEZs) are state-created instruments designed to stimulate economic activity through regulatory flexibility, tax incentives, or labor arrangements. Crucially, they remain embedded within the sovereignty of the host state and subject to ultimate public authority.

Privately governed cities and network-state initiatives go further. They do not merely operate under exceptions to the law; they often seek to replace or bypass public governance mechanisms altogether. Legal systems, dispute resolution, taxation, and regulation are privatized and embedded in contractual arrangements rather than public statutes.

From a governance standpoint, the distinction is critical. SEZs retain democratic accountability through the host state, even if imperfectly. Private cities frequently lack electoral legitimacy, independent oversight, and transparent checks and balances. Residents resemble customers or contractors more than citizens.

This shift transforms governance risk. What appears as efficiency or innovation may conceal accountability gaps, power asymmetries, and limited recourse for affected stakeholders. For boards, regulators, and auditors, privately governed cities represent not an extension of SEZ logic, but a fundamentally different governance paradigm with higher systemic risk.Special economic zones (SEZs) are state-created instruments designed to stimulate economic activity through regulatory flexibility, tax incentives, or labor arrangements. Crucially, they remain embedded within the sovereignty of the host state and subject to ultimate public authority.

Privately governed cities and network-state initiatives go further. They do not merely operate under exceptions to the law; they often seek to replace or bypass public governance mechanisms altogether. Legal systems, dispute resolution, taxation, and regulation are privatized and embedded in contractual arrangements rather than public statutes.

From a governance standpoint, the distinction is critical. SEZs retain democratic accountability through the host state, even if imperfectly. Private cities frequently lack electoral legitimacy, independent oversight, and transparent checks and balances. Residents resemble customers or contractors more than citizens.

This shift transforms governance risk. What appears as efficiency or innovation may conceal accountability gaps, power asymmetries, and limited recourse for affected stakeholders. For boards, regulators, and auditors, privately governed cities represent not an extension of SEZ logic, but a fundamentally different governance paradigm with higher systemic risk.

FAQ 3 – Why is “voluntary participation” a weak safeguard in governance terms?

Proponents of network states often argue that governance risks are mitigated because participation is voluntary: individuals can choose to join or leave. In governance theory, this argument is misleading.

Voluntariness at entry does not guarantee fairness over time. Once individuals commit their livelihoods, housing, education, and social networks to a governance system, exit becomes costly and asymmetrical. Capital and founders retain mobility; residents often do not.

Corporate governance learned this lesson long ago. Employment contracts are voluntary, yet power imbalances persist. States learned it earlier still: citizenship cannot be reduced to consumer choice without undermining legitimacy.

Good governance recognizes that voice matters more than exit. Democratic systems institutionalize dissent, representation, and accountability precisely because exit is not a sufficient protection against abuse. Network states frequently minimize voice while overstating exit.

For governance professionals, this highlights a core risk: systems designed around voluntariness may still produce coercive outcomes if power is concentrated and accountability mechanisms are weak.

FAQ 4 – What role does venture capital play in shaping these governance models?

Venture capital does more than provide funding; it embeds a governance philosophy. VC-backed structures prioritize speed, scalability, founder control, and exit opportunities. These principles work well for startups but are ill-suited for governance systems intended to endure across generations.

When venture capital finances network states or privately governed cities, term sheets effectively function as constitutional documents. Decision rights, dispute mechanisms, and control structures are shaped by investor priorities rather than public deliberation.

This creates structural tension. Venture capital seeks liquidity and optionality; governance requires stability and legitimacy. Investors can exit. Residents cannot. The result is governance optimized for capital efficiency rather than social resilience.

For boards and regulators, the lesson is clear: funding sources shape governance outcomes. Where venture capital becomes the primary architect of public-like institutions, governance risk increases—not because of intent, but because of misaligned incentives.

FAQ 5 – Why do traditional audit and assurance models struggle with network states?

Audit and assurance frameworks rely on statutory authority, defined reporting entities, and enforceable disclosure obligations. Network states deliberately operate outside these conditions.

They are not public entities, yet they exercise public functions. They are not corporations in the traditional sense, yet they control territory, rules, and enforcement mechanisms. As a result, there is often no independent audit mandate, no supreme audit institution, and no obligation to report to affected stakeholders.

Self-reporting and private arbitration replace public scrutiny. Transparency becomes selective. Accountability becomes contractual rather than civic.

For auditors, this raises a fundamental challenge: how to uphold the public interest when governance structures evade traditional oversight. While auditors cannot audit states, they must recognize when corporate arrangements begin substituting public authority and escalate concerns accordingly.

The absence of audit does not eliminate risk. It magnifies it.

FAQ 6 – What does this trend mean for the future of corporate governance?

The emergence of network states signals that corporate governance must evolve beyond firm-level optimization. As corporations and their founders exert influence over infrastructure, territory, and rule-making, governance frameworks must become power-aware rather than entity-bound.

Future corporate governance will need to address questions of legitimacy, societal impact, and accountability that extend beyond shareholders and financial performance. Boards must understand when strategic decisions have public consequences. Regulators must supervise functions, not just legal forms. Auditors must interpret public interest more broadly.

Most importantly, governance must reassert its core purpose: not enabling power, but restraining it. Efficiency without legitimacy is fragile. Innovation without accountability is unstable.

Network states are unlikely to replace traditional states. But they are already reshaping the governance landscape—and exposing where existing models fall short.

Tech entrepreneurs creating private states

Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states Tech entrepreneurs creating private states