1. Introduction and Scope – IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments

show

IAS 40 Investment Property governs how entities recognize, measure, and disclose real estate held either to earn rentals, for capital appreciation, or both. The standard’s boundary lines intersect with several other IFRS standards—IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment, IFRS 16 Leases, and IAS 2 Inventories—making judgment a central theme.

Unlike many standards that rely mainly on measurement estimation, IAS 40 demands judgment at every stage: classifying an asset as investment property, determining its measurement basis, interpreting “change in use,” and substantiating fair-value assumptions. These decisions have major effects on both reported profit and key ratios such as return on assets, EBITDA, and gearing.

IAS 40.5–15 defines investment property as land or a building—or part thereof—held by the owner or by the lessee under a finance lease to earn rentals, for capital appreciation, or both. A property used in the production or supply of goods or services, or for administrative purposes, falls under IAS 16 instead. Similarly, property held for sale in the ordinary course of business is an inventory asset governed by IAS 2.

The first layer of judgment lies in establishing management’s intent—an inherently forward-looking assessment. For example, when a developer acquires land, is the primary objective resale at a profit (inventory) or rental yield (investment property)? That intention guides not only classification but also subsequent measurement (fair value vs cost) and disclosure.

Read more from the IFRS Accounting Standards Navigator on IAS 40 Investment Property on ifrs.org

2. Delineation from Other Standards

a. Investment Property versus Owner-Occupied Property

IAS 40.9 notes that if a property is partly held for rentals and partly for own use, and the portions can be sold or leased separately, they are accounted for separately under IAS 40 and IAS 16 respectively. When the portions cannot be sold or leased separately, the property is treated as owner-occupied—unless the owner-occupation is “insignificant.”

This concept of “insignificant use” has proven fertile ground for enforcement debate. For example:

-

British Land plc (2022 Financial Statements) disclosed that a small proportion of space within certain mixed-use developments was occupied by group entities for marketing and management purposes. The company judged the self-occupied space “insignificant relative to total lettable area,” thus retaining IAS 40 classification for the entire property.

-

Conversely, Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield SE (2023) reclassified certain Paris retail complexes partly used for corporate events to IAS 16, concluding the internal occupation was “substantial” in economic terms even if the area metric was limited.

These opposite treatments demonstrate that the basis of measurement is not merely geometric; qualitative considerations—such as whether self-use generates direct economic benefit or primarily supports rental activities—also influence classification.

b. Investment Property versus Inventory

Real-estate developers often hold unsold units pending sale or lease. IAS 40.9(c) directs that property being constructed or developed for future sale is inventory (IAS 2), while property under construction for future rental or capital appreciation is investment property (IAS 40).

In the CapitaLand Limited (2021) statements, the Singaporean group disclosed significant management judgment in distinguishing investment properties under development from properties intended for sale. Projects within its “Integrated Developments” portfolio were assessed individually: those retained for long-term leasing were reclassified to investment property once construction reached a sufficiently advanced stage.

Such judgments require an articulated business-model rationale approved by governance bodies, since reclassification can materially shift reported assets from “current” to “non-current,” altering gearing and performance metrics.

c. Investment Property versus Leased Asset (IFRS 16)

IAS 40 applies both to owned property and to property held by a lessee as a right-of-use asset if it meets the investment-property definition. This dual application leads to nuanced judgments.

For instance, Goodman Group (2022) disclosed several long-term ground leases under which it acts as lessee while sub-leasing the land to third parties. Management judged these right-of-use assets as investment property, measuring them at fair value under IAS 40 rather than depreciated cost under IFRS 16. The fair value exceeded carrying cost by approximately AUD 380 million, directly affecting profit.

Such cases underline the importance of cross-standard reasoning: the nature of economic benefits—not the legal form of ownership—drives classification.

Read more in Landlord Lease term

3. Recognition and Derecognition

Investment property is recognized when—and only when—it is probable that future economic benefits will flow to the entity and the cost can be measured reliably (IAS 40.16). That simple rule conceals substantial interpretive work in practice.

a. When does recognition begin?

For properties under construction, the timing of recognition depends on whether the entity controls the underlying asset and bears construction risk. For instance, if a developer acquires land but has not yet secured permits, recognition may be deferred.

Vonovia SE (2023) described its approach: “Properties are recognized as investment property upon transfer of legal title or, where earlier, when control and risk pass to the Group.” This formulation acknowledges that substance may precede legal form.

b. Derecognition events

Derecognition occurs upon disposal or when the property permanently ceases to qualify as investment property (IAS 40.66). For example, converting a leased office into the entity’s own headquarters is a change in use. At that date, the property’s fair value becomes its deemed cost for IAS 16 purposes.

A practical illustration arose in British Land (2022), which converted part of its Broadgate development into corporate offices. The company derecognized £145 million of investment property at fair value and recognized the same amount as owner-occupied property. Audit committee minutes recorded that “the reclassification reflects a strategic change of use and not a valuation maneuver,” underlining the governance sensitivity of such transactions.

c. Estimation uncertainty at disposal

When properties are sold with contingent consideration (e.g., price-adjustment clauses based on future occupancy), determining the fair value of that contingent element is inherently uncertain. IAS 40 defers to IFRS 13 and IFRS 9, but management must still disclose the basis of estimation and any significant unobservable inputs.

Read more: Acquisition of investment properties – How 2 best account it

4. Initial Measurement

Upon recognition, an investment property is measured at cost, including transaction costs (IAS 40.20). The straightforward rule conceals a complex web of allocation and capitalization judgments.

a. Determining directly attributable costs

Which expenditures qualify as “directly attributable”? According to IAS 40.21, these include professional fees, property transfer taxes, and other transaction costs. However, internal staff costs and general overheads pose judgmental boundaries.

For example, Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield (2023) capitalized staff time directly related to project management but expensed administrative overheads. The group disclosed that “allocation is based on timesheet data and management estimates of effort,” illustrating that even within a Big-Cap real-estate REIT, estimation techniques matter.

b. Portfolio acquisitions and fair value allocation

When multiple properties are purchased in a single transaction, the purchase price must be allocated to individual assets based on relative fair values. For example, CapitaLand (2021) acquired a mixed portfolio of office towers and retail centers. Management allocated total consideration based on external valuations per asset, acknowledging “valuation uncertainty in allocating to assets with limited market comparables.”

The audit committee reviewed the methodology and external appraisers’ credentials—a clear example of governance oversight over accounting estimates.

c. Business combination versus asset acquisition

Judgment also arises in deciding whether the purchase of a portfolio constitutes a business combination under IFRS 3 or an asset acquisition. The implications differ: in a business combination, transaction costs are expensed and goodwill may arise; in an asset acquisition, transaction costs are capitalized.

Goodman Group (2022) evaluated several acquisitions and concluded they were asset purchases rather than business combinations, noting that “no organized workforce or substantive processes” were acquired. Such conclusions hinge on the assessment of “inputs and processes”—a subtle but material judgment.

5. The Policy Choice: Fair Value or Cost Model

At initial recognition, all investment properties are measured at cost, but IAS 40.30 offers a subsequent-measurement choice between the fair value model and the cost model. Once chosen, the policy must be applied to all investment properties, with changes allowed only if they provide more relevant and reliable information (IAS 8).

a. Nature of the policy choice

The selection is not merely technical—it defines the entity’s financial-reporting philosophy. The fair value model introduces volatility but arguably more transparency, while the cost model offers stability at the expense of current-market insight.

In practice, REITs and property funds typically prefer the fair value model, while manufacturing or diversified groups often choose cost.

-

Vonovia SE (2023) uses fair value, explaining that it “provides more relevant information to users given the nature of the business.” The resulting remeasurement gain of €1.8 billion was, however, heavily scrutinized in German financial media when subsequent market values declined.

-

Shell plc (2023), by contrast, retains the cost model for certain industrial land holdings, noting that “fair value measurement would not be reliable given absence of active markets.”

This demonstrates that relevance and reliability remain judgment calls, rooted in business purpose and data availability.

b. Governance implications

Adopting the fair-value model increases dependence on appraisers and internal valuation models. Boards must ensure independence, document key assumptions, and evaluate whether fair values truly represent exit prices as per IFRS 13.

Audit committees commonly review:

-

competence and independence of external valuers;

-

internal sensitivity analyses on capitalization rates and discount factors;

-

procedures for challenge and corroboration.

Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield (2023) disclosed that its audit committee holds a dedicated “valuation deep-dive” session each half-year, challenging both management and external valuers on assumptions regarding yields, rent growth, and exit cap rates.

Such practices demonstrate that fair-value estimation is as much governance art as accounting science.

6. Estimating Fair Value: Assumptions, Techniques and Judgments

Under the fair-value model, each reporting date requires entities to measure investment property at its fair value, defined in IFRS 13 as the price that would be received to sell an asset in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date. IAS 40.33 mandates recognition of gains or losses in profit or loss, placing heavy emphasis on valuation integrity and disclosure of key assumptions.

a. Selecting the Valuation Approach

Three principal valuation techniques are accepted under IFRS 13: the market approach, income approach, and cost approach. Choice depends on data availability, property type, and market liquidity.

-

Market approach – based on recent transactions for similar properties. For example, British Land 2022 FS disclosed that approximately 60 % of its UK portfolio was valued using direct comparison to observable market deals, with adjustments for location and condition.

-

Income approach – projecting rental cash flows and discounting them at a market-derived rate. Vonovia SE 2023 noted that 85 % of its valuations used discounted-cash-flow (DCF) models with 10-year horizons and terminal yields between 3 % and 4 %.

-

Cost approach – used when market or income data are unavailable, often for specialized assets. Shell plc 2023 applied this for certain energy infrastructure properties.

Choosing among these techniques requires professional judgment that balances relevance and reliability. Boards must confirm that chosen models reflect exit-price assumptions and not entity-specific values.

b. Determining Key Inputs and Assumptions

The most critical estimation areas include:

-

Capitalization and discount rates. Minor changes in discount rate can materially shift fair value. Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield 2023 reported that a 25-basis-point movement in capitalization rates would change portfolio fair value by ± €850 million.

-

Market rental growth. Expectations for rental inflation and void periods embed subjectivity. CapitaLand 2021 explained that growth assumptions derived from independent market studies were benchmarked against internal budgets and capped for prudence.

-

Vacancy allowance and tenant credit risk. During 2020–2023, post-pandemic shifts in office demand led many groups to raise vacancy assumptions; failure to do so became an enforcement issue for ESMA in 2022.

-

Transaction costs and liquidity discounts. IAS 40 requires fair value to exclude transaction costs, yet many appraisals include them by convention. Reconciling appraisal values to IFRS values demands explicit adjustment.

c. Valuer Independence and Governance

Although IAS 40 does not mandate external valuers, most listed property groups engage independent appraisers for credibility. Governance frameworks typically require:

-

rotation of valuers every 3–5 years;

-

dual sign-off (management + external valuer);

-

audit-committee review of key sensitivities.

British Land 2022 disclosed that its valuation committee—separate from management—reviews assumptions quarterly and challenges outliers. Such structures illustrate how internal control mitigates estimation bias.

d. Level 3 Measurements and Disclosure

Under IFRS 13, most investment-property valuations qualify as Level 3 because unobservable inputs significantly influence fair value. Entities must disclose quantitative sensitivity analyses. For example, Goodman Group 2022 presented a table showing the effect of ± 0.25 % in discount rates, altering net assets by ± AUD 470 million.

These disclosures are not merely compliance artifacts; they enable users to evaluate estimation uncertainty—an essential component of the Significant Judgments and Estimates narrative.

7. Changes in Use and Reclassification

IAS 40.57–64 require that an entity transfer a property to or from investment property only when there is evidence of a change in use. Such evidence includes: commencement of owner-occupation, start of development with a view to sale, or inception of an operating lease to another party.

a. Timing and Evidence of Change

Determining when the change occurs can be contentious. The standard warns that a change in management intent alone does not constitute evidence. Instead, objective indicators are required—such as signing a lease, occupancy certificates, or board approval.

In Vonovia SE 2023, several residential blocks were reclassified from investment property to inventory once conversion permits were obtained for sale. Management justified the timing on the basis that “marketing had commenced,” not merely because a strategic decision was taken.

Similarly, British Land 2022 reclassified a redevelopment site to property, plant and equipment once it began to house the group’s headquarters—supported by physical relocation rather than board minutes alone.

b. Measurement at Date of Transfer

At the transfer date, the fair value of the property becomes its deemed cost for subsequent accounting. If a property moves from owner-occupied to investment, any difference between carrying amount and fair value is treated as a revaluation under IAS 16, with gains in OCI. Conversely, transfers into inventory trigger recognition of fair-value gains or losses in profit or loss.

CapitaLand 2021 disclosed reclassification of a mixed-use tower from “development property” to “investment property” once pre-leasing reached 70 %. A fair-value gain of SGD 112 million was recognized. Auditors highlighted this as a key audit matter, noting significant judgment in identifying the precise change-in-use date.

c. Temporary Vacancy and Refurbishment

A temporary vacancy or refurbishment does not constitute a change in use (IAS 40.58). Yet in practice, entities may be tempted to reclassify to capture fair-value gains. ESMA’s 2021 enforcement report cited multiple issuers for premature reclassification when refurbishment merely aimed to preserve market value.

Governance frameworks should therefore require explicit board documentation of the event triggering reclassification and an assessment of whether the property’s function—not its income—has changed.

8. Impairment and Recoverability Under the Cost Model

Entities applying the cost model measure investment property at cost less accumulated depreciation and impairment. IAS 36 governs impairment testing, and its principles mirror those for other non-current assets. Nevertheless, the interplay with IAS 40 introduces specific judgmental challenges.

a. Identifying Cash-Generating Units (CGUs)

Investment properties often generate cash inflows largely independent of each other, implying that each property may form its own CGU. However, when properties share amenities or tenants across sites, aggregation may be necessary.

In Goodman Group 2022, management defined CGUs at the “industrial estate” level, grouping adjacent warehouses that share access roads and utilities. This aggregation avoided arbitrary allocation of common costs but required justification that cash flows were interdependent.

b. Triggering Events and Market Indicators

IAS 36.12 lists external and internal indicators of impairment. For investment property at cost, relevant triggers include:

-

declines in market rent or occupancy;

-

physical damage or obsolescence;

-

adverse regulatory changes.

After 2022’s rapid interest-rate increases, several European groups reviewed their cost-model portfolios for impairment. Shell plc 2023 wrote down certain industrial land in Germany by $47 million, citing “reduced redevelopment potential.” Management disclosed that the recoverable amount was based on value-in-use, not fair value, consistent with IAS 36.

c. Estimating Recoverable Amount

Recoverable amount is the higher of fair value less costs of disposal and value in use. The latter requires discounting expected cash flows from the property. Choosing discount rates and terminal growth assumptions introduces familiar estimation uncertainty.

For illustration, Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield 2023 described its impairment test on cost-model car parks: a discount rate of 6.5 % and zero terminal growth. A 1 % increase in the rate would reduce recoverable amount by €65 million. Such quantitative disclosure exemplifies good practice in communicating estimation sensitivity.

d. Interaction with Fair-Value Model Entities

Even entities using the fair-value model must assess whether carrying amounts reflect recoverable value. Although IAS 40 precludes separate impairment testing, the reliability of fair-value estimates effectively serves as a proxy for impairment analysis. Governance oversight should ensure that external valuations are timely and reflect post-balance-sheet market events.

e. Governance Perspective

Boards should recognize that impairment judgments are not purely mechanical. In periods of market stress, management optimism can delay recognition of losses. Audit committees must challenge assumptions such as “temporary downturn” narratives and ensure that scenario analyses include downside cases. Documentation of these deliberations strengthens both the audit trail and investor confidence.

9. Disclosure of Significant Judgments and Estimation Uncertainty

IAS 1 requires entities to disclose judgments that have the most significant effect on the financial statements (§122) and information about key assumptions concerning the future and other major sources of estimation uncertainty (§125). In the context of investment property, these disclosures act as the bridge between management’s subjective decisions and users’ understanding of how results might change if assumptions move.

a. Structure and Purpose of Disclosures

High-quality disclosure does more than list numbers—it explains reasoning. IFRS Practice Statement 2 (Making Materiality Judgements) notes that entities should focus on judgments that “could reasonably be expected to influence decisions of primary users.” For investment property, this typically includes:

-

classification basis (why a property qualifies as investment property);

-

measurement model chosen (cost vs fair value) and reasons;

-

key valuation techniques and inputs;

-

sensitivity to changes in unobservable inputs;

-

and reclassification events or impairment triggers.

b. Examples of Disclosure Practice

Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield SE (2023) devoted four pages to valuation methodology, describing DCF assumptions, terminal capitalization rates, and sensitivity analyses by geography. The group explicitly linked its fair-value hierarchy (IFRS 13 Levels 2 & 3) to risk management oversight, noting that “Level 3 inputs reflect management assumptions supported by external evidence where available.”

British Land plc (2022) provided narrative disclosure on judgments applied in assessing whether mixed-use sites remained investment property:

“The Board considered the scale of self-occupation and the strategic intention of long-term holding. On balance the property continues to be held for investment purposes.”

Such wording demonstrates how qualitative reasoning complements quantitative sensitivity data.

Vonovia SE (2023) illustrated estimation uncertainty by quantifying the effect of ± 25 basis-point changes in discount rates and ± 0.5 % changes in market rents, translating these into a €2.4 billion swing in fair value—one of the clearest numeric sensitivities among European REITs.

c. Granularity and Aggregation

IAS 1 § 31 discourages immaterial clutter. However, regulators have found that many entities disclose overly aggregated information—e.g., one sensitivity analysis for an entire global portfolio. ESMA’s 2023 enforcement priorities urged issuers to “disaggregate material sources of estimation uncertainty when economic environments differ substantially between markets.”

CapitaLand (2021) complied with this expectation by separating Singapore, China, and Vietnam portfolios, disclosing distinct yield ranges and risk premiums. The group noted that “a 50 bps yield movement has different implications across markets with varying leverage levels.” This geographic segmentation reflects good IFRS 13 practice and improves user insight.

d. Disclosure of Valuation Methodology

IFRS 13 § 93(h)–(i) requires disclosure of valuation techniques and inputs for Level 3 measurements. Many preparers include tables summarizing:

| Technique | Key Inputs | Range (%) | Sensitivity Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCF | Discount rate | 5.0–7.0 | ± €200 m per 25 bps change |

| Capitalization | Cap rate | 4.0–5.5 | ± €150 m per 25 bps change |

Yet IAS 1 expects narrative context—why management considers inputs appropriate. Goodman Group (2022) explained that discount rates “reflect current risk-free rates plus property-specific risk premiums calibrated to observed transaction evidence.” This narrative elevates disclosure from compliance to communication.

e. Reconciliation of Carrying Amounts

IAS 40 § 76(c) requires a reconciliation of carrying amounts at the beginning and end of the period, showing additions, disposals, fair-value changes, transfers, and exchange differences. The reconciliation often reveals management’s activity pattern. For example, Vonovia 2023 disclosed disposals of €1.1 billion following Germany’s rent-control reforms, signaling portfolio repositioning beyond the headline fair-value change.

f. Forward-Looking Transparency

Although IFRS prohibits recognition of future capital expenditure or planned developments, entities frequently provide narrative forward-looking insight. British Land 2022 included an “outlook” statement describing expected stabilization of yields and tenant demand—clearly labeled as non-IFRS information but highly valued by analysts. Such voluntary transparency supports trust in inherently judgment-based valuations.

g. Common Pitfalls in Practice

Regulators highlight recurring weaknesses:

-

Generic boilerplate language (“Valuations are subject to estimation uncertainty”) without quantification.

-

Inconsistent valuation date or methodology between subsidiaries.

-

Failure to disclose rationale for reclassification or model change.

-

Omission of sensitivity when Level 3 inputs dominate.

Enforcement examples show that even large issuers are not immune: in 2022, ESMA required one unnamed Euro Stoxx 50 property group to expand disclosures because its yield sensitivity ignored regional volatility.

10. Governance and Oversight Considerations

The high level of subjectivity in IAS 40 means that corporate-governance frameworks—board approval, audit-committee oversight, and independent valuation review—are integral to faithful representation.

a. Board Responsibility

Boards must approve accounting-policy elections (IAS 8) and ensure consistent application across subsidiaries. Many boards delegate detailed oversight to an audit or valuation committee, which meets with external appraisers and auditors at least semi-annually.

Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield 2023 disclosed that its Supervisory Board’s Audit Committee dedicates one meeting each half-year exclusively to valuation issues, reviewing:

-

methodology changes proposed by management;

-

appraisers’ independence declarations;

-

and alignment with market evidence.

Minutes are summarized in the annual report, reinforcing accountability.

b. External Valuers and Independence

While IAS 40 does not oblige use of external valuers, best practice—endorsed by RICS Red Book standards—supports independent valuation for transparency. Governance policies typically cover:

-

appointment and rotation criteria;

-

scope of engagement (e.g., percentage of portfolio externally valued);

-

conflict-of-interest assessment;

-

and documentation of management’s challenge process.

British Land 2022 rotated its principal valuer after ten years, citing “fresh perspective” as part of governance renewal. The company continued to cross-check new valuer assumptions against historical data to ensure continuity.

Also read: Separate lease and non-lease components.

c. Audit Committee’s Analytical Role

The audit committee serves as the key line of defense against valuation bias. Typical responsibilities include:

-

Reviewing fair-value hierarchy classification.

-

Challenging reasonableness of discount-rate movements versus market benchmarks.

-

Ensuring sensitivity disclosures align with actual internal risk assessments.

-

Evaluating impairment decisions under the cost model.

For instance, Vonovia 2023 reported that its audit committee challenged management’s assumption of stable rents amid rising interest rates. The eventual revision of discount rates by +0.25 % reduced reported profit by €340 million—an example of governance directly influencing financial results.

d. Interaction with Auditors

External auditors treat fair-value measurement of investment property as a key audit matter (ISA 701). Audit reports typically describe procedures such as evaluating competence of valuers, testing inputs, and assessing sensitivity analysis.

KPMG’s audit report on Goodman Group (2022), for example, described performing independent recalculations of fair-value models and benchmarking discount rates. The report noted that “small changes in assumptions could result in material valuation movement,” thereby reinforcing estimation sensitivity.

Such auditor transparency complements management disclosure and reassures users that oversight operates effectively.

e. Internal Controls over Valuation Process

Strong internal control frameworks include:

-

documented valuation policies referencing IFRS 13 and IAS 40;

-

segregation between asset management (performance incentives) and finance teams (reporting);

-

approval hierarchy for valuation adjustments;

-

IT controls over property databases feeding valuation models.

In 2021 the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM) identified weaknesses where rent databases feeding valuation models were updated manually without audit trail, stressing that “data integrity is a prerequisite for reliable fair-value reporting.”

f. Ethical Dimension and “Tone at the Top”

Because valuation gains can inflate short-term performance, ethical culture matters. The board must signal that transparency outweighs earnings management. A telling case was Land Securities Group (2020), which voluntarily disclosed a £368 million fair-value loss during the pandemic, emphasizing that “long-term credibility of valuation policy supersedes temporary earnings impact.” Analysts rewarded the group with higher governance-quality scores despite the loss.

g. Integration with Risk Management and ESG Reporting

Investment property valuation increasingly intersects with sustainability disclosures under CSRD and ESRS E1 (Environment). Energy performance, green-lease provisions, and physical climate-risk assessments influence fair value and must align across reporting frameworks.

CapitaLand Investment (2023 Sustainability Report) linked climate-risk scenario outcomes to capitalization-rate adjustments disclosed under IAS 40. This integration exemplifies how forward-looking ESG data enhance, rather than dilute, IFRS reporting integrity.

h. Lessons from Enforcement and Case Studies

-

ESMA 2022 Findings: inadequate sensitivity disclosures were the most common IAS 40 deficiency. ESMA advised issuers to ensure that “quantitative disclosure reflects management’s actual internal sensitivity analysis.”

-

FRC UK Thematic Review (2023): commended British Land for linking narrative commentary to quantitative sensitivities and criticized others for “listing” inputs without analytical context.

-

ASIC Australia (2022): highlighted Goodman Group’s comprehensive audit-committee documentation as good practice in ensuring fair-value credibility.

These case studies show that governance bodies not only comply with IFRS rules but also shape market perception of reliability.

i. Governance Check-List for Boards

| Focus Area | Key Questions for Oversight |

|---|---|

| Policy Choice | Has the board approved the continued use of fair-value model and documented rationale? |

| Valuation Process | Are valuers independent, rotated periodically, and benchmarked to market data? |

| Assumptions | Are key inputs reviewed for consistency with macro-economic indicators? |

| Sensitivity | Does disclosure quantify reasonably possible changes? |

| Reclassifications | Are change-of-use events supported by objective evidence? |

| Ethics | Is performance remuneration insulated from short-term valuation gains? |

Embedding such a checklist into annual-report governance sections turns what could be perfunctory disclosure into a demonstration of accountability.

11. Practical Illustrations and Case-Law Trends

a. Market-Volatility and Revaluation Timing

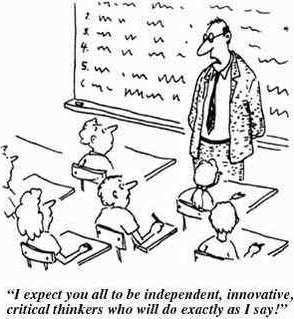

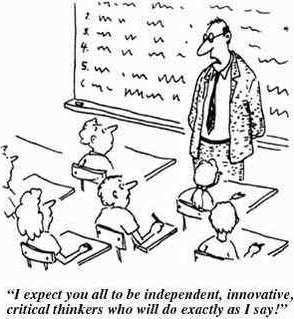

IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments

During 2022–2023, rising interest rates and falling real-estate valuations created visible tension between accounting neutrality and market optimism.

-

Vonovia SE (2023) faced a €10.7 billion fair-value loss after adjusting discount rates upward by 100 bps. The company explained the move as “reflecting a changed macro-environment,” emphasizing governance control: valuation models were approved jointly by the audit committee and external appraisers.

-

British Land plc (2023) took a similar 12 % portfolio write-down, but disclosed that “valuation frequency increased to quarterly” as part of risk governance. The timing of fair-value updates thus became a governance signal rather than merely an accounting exercise.

Both examples highlight that under IAS 40, the decision of when to measure can be as judgmental as how to measure.

b. Enforcement Actions and Regulator Focus

The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) 2023 enforcement report identified recurring deficiencies:

-

Unsupported assumption of “temporary” value declines;

-

Opaque sensitivity analysis;

-

Failure to justify classification of partially owner-occupied property.

In one anonymized case, a Southern-European issuer was required to restate its 2021 statements because management had deferred fair-value losses despite observable market evidence. ESMA concluded that “management intent cannot override market data.”

c. IFRS Interpretations Committee (IFRIC) Precedent

The IFRIC Agenda Decision (March 2019) clarified that a right-of-use asset under a head lease can be investment property if sub-leased to third parties and otherwise meets the IAS 40 definition. This interpretation eliminated inconsistency between IFRS 16 and IAS 40 and illustrated how cross-standard judgment must be anchored in economic substance.

d. Litigation and Valuation Misstatement

In Henderson Global Investors v XYZ REIT (UK High Court, 2021), investors alleged negligent over-valuation. The court dismissed the claim but noted that the REIT’s audit-committee minutes were “instrumental evidence of reasonable governance.” The case underscores that documentation of challenge protects not only accounting credibility but legal defensibility.

e. ESG and Sustainability as Emerging Valuation Drivers

Post-2023, “green premiums” and “brown discounts” increasingly affect fair-value assumptions.

-

CapitaLand Investment 2023 Sustainability Report quantified a 10–15 bps yield improvement for BREEAM-certified assets.

-

Goodman Group 2022 observed that energy-inefficient warehouses required higher cap rates, reducing valuations by AUD 250 million.

IAS 40 itself is silent on sustainability adjustments, yet governance reality demands boards oversee the consistency between fair-value estimates and sustainability disclosures (ESRS E1, E5).

f. Best-Practice Illustration – Integrated Oversight

A synthesis of good practice observed across issuers:

-

External valuations covering ≥ 90 % of portfolio annually;

-

Dual-signature process (CFO + Head of Valuation);

-

Audit-committee session with valuer without management present;

-

Reconciliations between appraiser assumptions and business-plan forecasts;

-

Quantified sensitivities and geographic segmentation.

These habits translate IAS 40’s principles into a culture of disciplined transparency.

12. Conclusion and Governance Lessons

IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments

IAS 40 remains one of the most judgment-laden standards in IFRS. Its application intertwines economics, valuation science, and governance ethics.

a. Nature of Judgment

Every major decision under IAS 40—classification, policy choice, timing of reclassification, selection of valuation model, estimation of inputs—depends on professional judgment exercised within a documented governance framework. The standard’s flexibility rewards consistency and punishes opportunism.

b. Governance as the Anchor

Boards and audit committees act as the institutional conscience of valuation. Their effectiveness can be gauged not by absence of fair-value volatility, but by the transparency and discipline with which volatility is recognized and explained.

Good governance in investment-property reporting means:

-

independence of valuers and robustness of challenge;

-

ethical restraint against “valuation smoothing”;

-

linkage between ESG factors and valuation assumptions;

-

clear, entity-specific disclosures connecting narrative and numbers.

c. Alignment with the Broader Reporting Ecosystem

IAS 40 judgments now intersect with:

-

IFRS 13 (fair-value hierarchy),

-

IAS 1 (judgments & estimation uncertainty),

-

IAS 36 (impairment testing for cost model), and

-

CSRD/ESRS (sustainability-related drivers).

The next stage of best practice will likely involve integrating sustainability data—energy intensity, occupancy risk, transition planning—directly into fair-value sensitivity analysis.

d. The Ethical Imperative

Transparent valuation is not merely a compliance matter. It underpins capital-market trust. As Land Securities 2020 showed, reporting a £368 million loss honestly can strengthen credibility more than avoiding it. The ethical tone of management, supported by audit-committee vigilance, is the real safeguard of faithful representation.

In short:

IAS 40 converts corporate real estate into a test of integrity. The numbers may measure property; the disclosures measure governance.

Frequently Asked Questions – IAS 40 Investment Property Estimates

FAQ 1 – What is the key judgment under IAS 40?

The most critical judgment under IAS 40 lies in determining whether a property qualifies as investment property. This depends on management’s intent and the property’s actual use. A building held to earn rentals or for capital appreciation qualifies, but property used for production, administration, or resale does not.

Management must assess substance over form, considering control, duration of ownership, and separability of uses. Documentation—such as board minutes, leases, or development plans—supports the classification. Regulators expect clear rationale distinguishing investment property (IAS 40) from owner-occupied property (IAS 16) or inventory (IAS 2), since this decision drives recognition, measurement, and disclosure outcomes.

FAQ 2 – When should a property be reclassified?

Reclassification is required only when there is objective evidence of a change in use—not merely a shift in management intention. Evidence includes starting owner-occupation, commencement of development for sale, or execution of a lease to an independent tenant. The fair value at that date becomes the new carrying amount, which demands estimation judgment.

Premature or unsupported reclassifications can distort earnings and mislead users, so governance controls and audit-committee documentation are vital. IAS 40.57–64 emphasize substance: a temporary vacancy or refurbishment does not justify transfer. Transparent disclosure of timing, reasoning, and valuation impact supports faithful representation.

FAQ 3 – How do fair-value and cost models differ in governance impact?

Choosing between the fair-value and cost models is not purely technical—it defines how the organization communicates performance. The fair-value model introduces recurring remeasurement in profit or loss, creating volatility but also transparency. It requires independent valuation, management challenge, and robust audit-committee oversight. The cost model provides stability but shifts attention to impairment indicators under IAS 36.

Each approach entails different internal controls, documentation standards, and disclosure obligations. Boards must approve the accounting-policy choice and review its continued relevance annually. The governance implication is clear: the chosen model influences investor confidence and the perceived integrity of reporting.

FAQ 4 – What disclosures does IAS 1 require for investment property?

IAS 1.122–125 require entities to disclose both judgments and key sources of estimation uncertainty. For investment property, this means explaining classification rationale, valuation techniques, key assumptions, and sensitivity to changes in unobservable inputs. Boilerplate statements are insufficient—entities must quantify effects where possible and relate them to real economic variables such as rental growth or yield shifts.

The objective is to help users understand how results might change if assumptions differ. Regulators like ESMA encourage granular, property-level sensitivity disclosures, especially when markets diverge by region. High-quality disclosure transforms judgment from a black box into informed transparency.

FAQ 5 – Can right-of-use assets be investment property?

Yes, IAS 40 applies equally to properties held by lessees as right-of-use (ROU) assets, provided the lessee sub-leases them to third parties or holds them for capital appreciation. The IFRIC Agenda Decision (March 2019) confirmed that a ROU asset under IFRS 16 can qualify as investment property when economic substance aligns with IAS 40’s definition.

The judgment involves assessing control, duration of sub-lease, and exposure to residual value. Entities must also consider measurement consistency: if using the fair-value model, ROU assets are remeasured to fair value, not depreciated cost. Clear disclosure of policy alignment prevents confusion and enhances comparability.

FAQ 6 – How should ESG factors be reflected in fair value?

Although IAS 40 itself does not mention ESG, IFRS 13 requires fair value to reflect market participants’ assumptions—including sustainability factors that influence rents, occupancy, or yields. Buildings with strong energy performance certificates or green certifications often command lower capitalization rates, while carbon-intensive assets may face “brown discounts.”

Boards and valuers must integrate climate and transition risks into valuation models and disclose how assumptions align with sustainability reporting under CSRD or ESRS E1. Transparent linkage between fair-value estimates and ESG metrics reduces greenwashing risk and strengthens investor trust. Sustainability is thus emerging as a legitimate estimation dimension under IAS 40.

IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments

IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments IAS 40 Investment Property Judgments